* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

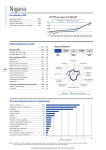

Download The Global Competitiveness Index 2012–2013: Country Profile

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript