* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Instructor Handout 1 TSP 1776

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

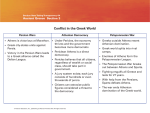

Instructor Hand out Use with TSP 071F1776 Peloponnesian War Introduction The war between Athens and the Athenian empire versus Sparta, Thebes, Corinth, and other members of the Peloponnesian Confederacy 431 - 404 B.C.E. Large scale campaigns and heavy fighting took place from Sicily to the coast of Asia Minor and from the Hellespont and Thrace to Rhodes. It was the first war in history to be recorded by an eyewitness historian of the highest caliber. It has come down through history as the archetypal war between a commercial democracy and an agricultural aristocracy and a war between a maritime superpower and a continental military machine. Thycidides' history is itself a classic, which for generations was considered a foundation of a proper education. The war began on 4 April 431 B.C. with a Theban attempt to surprise Plataea, Athens' ally and outpost on the northern base of Cithaeron. It ended on 25 April 404 B.C., when Athens capitulated. The cities of the Boetian Confederacy under Theban leadership were Sparta's allies from the first. Syracuse and other Sicilian cities gave active help in the last part of the war. Argos, her hand tied by a treaty with Sparta, remained neutral during the first ten years, but as a democracy, was benevolently inclined towards Athens. Persia at first held aloof, waiting for an opportunity to regain her dominion over the Greek cities of the Asiatic seaboard, which Athens had liberated, but finally provided the crucial financial and logistic support required by Sparta to conduct a maritime offensive. Athens, was unpopular with many members of her own empire, but held most under control by her maritime supremacy. The war may be divided into three major periods or five phases: The Archidamian war: phase 1 431-427; phase 2 426-421 The Sicilian war: 421-413 The Ionian or Decelean War: phase 1 412-404; phase 2 407-404 Causes The underlying cause of the war was Sparta's fear of the growth of the power of Athens. This is Thucydides' own final judgment. The whole history of the rise and power of Athens in the 50 years preceding justifies this view, though the immediate occasion of the war concerned Corinth, Sparta's chief naval ally. Since the peace of 445 B.C. Pericles had consolidated Athenian resources, made Athens' navy incomparable, concluded in 433 B.C. a defensive alliance with the strong naval power Corcyra (Corinth's most bitter enemy), and renewed alliances with Rhegium and Leontini in the west. The very food supply of the Peloponnese from Sicily was endangered. In the Aegean Athens could always enforce a monopoly of seaborne trade. To this extent the Peloponnesian War was a trade war and on this ground chiefly Corinth appealed to Sparta to take up arms. The appeal was backed by Megara, nearly ruined by Pericles' economic boycott, and by Aegina a reluctant member of the Athenian Empire. But if Sparta had not also been eager for war then peace would have lasted. Sparta was waiting an opportunity that came when Athens was temporarily embarrassed by the revolt of her subject-ally Potidaea in Chalcidice in the spring of 432 B.C. The rebel city held out until the winter of 430 B.C. and its blockade meant a constant drain upon Athenian military, and naval resources. Sparta seized the opportunity. Confident of speedy victory she refused an offer of arbitration made by Pericles. Instead, Sparta sent an ultimatum that would have practically destroyed Athenian power. Pericles urged the people to refuse and Sparta declared war. Peloponnesian War: Phase 1 (431-427) In a war between the main military and main naval powers in Greece a decisive result was unlikely to occur quickly. Sparta relied on the traditional strategy of Greek warfare. She hoped that by invading Attica and destroying the crops she would force Athens either to sue for peace or come out to fight the standard set piece battle in which typical Greek wars were decided. In numbers as well as discipline and combat effectiveness of troops Athens was decidedly inferior to the Spartan-Theban forces. The defect in this strategy was that Athens unlike other Greek cities could not be starved into surrender, nor be made to fight a pitched battle by occasional occupation of its individual citizen's farm lands. Her food supply came principally from Egypt and Crimea. The the old king of Sparta, Archidamus, knew this and warned his people about it. But the Spartans were still confident in a quick victory in pursuing their strategy of annihilation. Pericles based his own confidence on his opposite strategy. He wanted only the status quo ante and not conquest, which was quite beyond the means available. Therefore, knowing his city walls were impregnable and connected Athens to the sea at Piraeus and his navy would be able to insure the food supply, he opted for a defensive strategy of attrition. When the Spartans invaded, the rural population of Attica moved into the city. Athens became an island impregnable to attack. Its great fleet would secure the empire against revolts from within and attacks from without and take the offensive to raid the Peloponnesian coast. Meanwhile, every spring and autumn the Athenian land army would devastate the lands of Sparta's allies (especially Megara) at the Corinthian Ismuth, while the Spartans were home tending to their own crops. If Megara could be recovered, then Spartan land access to Attica would be blocked and her Theban allies would not dare come down from the north unaided. The Periclean strategy also had weaknesses. He was too fearful of the effect that high casualties would have on public sentiment in a democracy, if he had conducted more aggressive offensive military actions. He had not seen the opportunities for combined land and naval actions to bring a higher intensity of war to Spartan territory with little risk in order to hasten the effect of the attrition on Sparta. The defect essentially was that the Athenian people's morale proved unequal to the strain, and, after his death, rushed into rash attempts to overreach their means. Meanwhile, the Spartans were stoic and persistent in the face of failure, until they found foreign resources sufficient to turn the tables on Athens. Chance too entered the lists, when in June 430 plague brought with the vital grain from Egypt or Libya swept the city, overcrowded with the rural refugees. Athenian troops sent north to reenforce the army besieging Potidaea merely brought the plague along. But no other Greek city suffered, thanks to the lack of contact during the war. Pericles himself died in 429. Megara held out, although starving. The Athenian naval raids on Sparta's coastal allies were too feeble to bother Sparta. Therefore it was Athens which suffered the attrition meant for Sparta. Athens' vast financial resources were strained and she began exacting even more onerous taxation from her empire, which only engendered more unrest and rebellion. In particular a strong force sent to operate from Cythera would have at least kept Sparta's armies out of Attica. Thus the admiral, Pericles, threw away the strategic opportunities available by the proper use of his navy. Athens began to offer peace in 430, but Sparta refused. In 430-29 Potidaea finally surrendered, boosting the Athenian position. Then in the fall of 429 Athens won two great naval battles at Chalcis and Naupactus. The later won by Phormio taking advantage of superior Athenian seamanship. In June 428 Mitylene on Lesbos revolted. In 427 the Spartan fleet under command of Alcidas retreated without even offering battle, instead of helping Mitylene, forcing the city to surrender in July. But this was countered by the surrender in August of Athens' ally, Plataea, to a Theban army which destroyed both population and city itself. In 426 Athens gained the upper hand in Corcyra, but only after a ghastly slaughter. This brought the war to a near stalemate. Peloponnesian War: Phase 2 (426-421) In 426 Athens began more active operations under direction of new political leaders of the democratic party, Cleon and Demosthenes. Despite continued resistance by the upper classes led by Nicias, they initiated a vigorous offensive strategy. Athenian forces attempted to carry the war to Boeotia (Thebes), Sparta, and even Sicily. In 426 two Athenian armies moved toward Thebes, one under Demosthenes via Acarnania under cover of an attack on Sparta's ally, Ambracia; and the other under Nicias via Tanagra. The plan failed. Demosthenes' force of mostly local allies was trapped and routed, although he managed to escape to Naupactus. Nicias, ever the reluctant warrior, won a small victory at Tanagra and then withdrew. To cover expenses Cleon in 425 raised the tribute from the empire. Sparta began reprisals. A large army under Eurylochus marched from Delphi, threatened Naupactus, and laid siege to Amphilochian Argos. Demosthenes won two great victories at Olpae and Idomene by clever tactical techniques. This destroyed Spartan hegemony, pushed Arcania and Abracia out of the war, and opened the way for the Athenian navy to Sicily. In 425 Athens won its greatest victory at Spacteria. Its fleet en route to Sicily put in at Navarino Bay and Demosthenes built and garrisoned a fort there on Pylos promontory. The Spartans attacked by land and sea. He drove off the assault on the fort, and the Athenian fleet, returning at his request, blocked the Spartan navy in the bay and cut off the Spartan force of 420 men on Spacteria island. Athens secured the surrender of the enemy fleet, leaving Sparta without one for many years. Cleon brought reinforcements, which enabled the Athenians finally to overwhelm the Spartan resistance and capture 292 prisoners including 120 Spartiates, who were taken to Athens. This was an unprecedented disgrace for Sparta. The "hostage" issue of these prisoners-of-war not only secured all Attica from Spartan attacks, but was played upon by Athens until Sparta sued for peace, which, foolishly, Cleon refused. In 424 all Athenian offensive plans failed. Their admirals were forced to return from Sicily, due to Syracusan policies, but were nevertheless severely punished by the democratic led assembly. In November their three- pronged offensive against Thebes was defeated at Delium, thanks to a new tactical deployment of Pagondas using a deep infantry wing and skillful use of cavalry. The Athenian attempt to capture Megara by treachery was blocked by the Spartan relief force under Brasidas. Brasidas then marched full speed through Boeotia and Thessaly to Chalcidice stirring up revolt and offering freedom. Amphipolis surrendered. In 422 Brasidas continued his victorious campaign despite Athenian reinforcements. Brasidas sallied from Amphipolis and defeated the Athenian force, killing Cleon, but dying in the process as well. Thus in one battle two of the greatest advocates and practitioners of offensive warfare died. Then, by April 11, 421 Nicias concluded a peace treaty between Athens and Sparta that he hoped would end the war. Peloponnesian War: Phase 3 (421-417) All the animosities and policy conflicts which divided the Greek cities remained during this period as all sides strove to regain their strength. Corinth and Thebes refused to adhere to the peace treaty. Neither Sparta nor Athens actually fulfilled its obligations, except that Athens did give up its Spartan prisoners. In 420 a new alliance of Athens, Argos, Mantinea, and Elis faced the Spartan - Boeotian Alliance. Athens now had a new democratic leader in Alcibiades. The reminder of the war was marked by the bitter internal political struggle between the democratic war party led by Alcibiades and the aristocratic (oligarchial) elements led by Nicias and others. This struggle led to outright treason, vicious internal partisan purges, and the final destruction of Athens' empire, hegemony, and very independence. Athens' third offensive strategy was the most ambitious conception so far, but it was ultimately negated by the internal opposition of Alcibiades' political opponents. Thanks to the new allies in the Peloponnese, she threatened Sparta at home and forced Sparta into pitched battle on home territory. Sparta responded to the crisis by bringing forth another great military leader in King Agis. Taking the initiative, Agis assembled a powerful army at Phlius by masterly night marching and descended from the north on Argos, but was forced to make a treaty and withdraw due to the failure of his Boeotian allies. However, a few months later Alcibiades was able to pressure the Argives into denouncing the treaty and threatening Tegea. Athens then sent only an inadequate force in support and Elis sent none at all. Agis brought up the full Spartan army and in August 418 won the largest land battle of the war at Mantinea. This not only restored Spartan self-confidence and prestige but also knocked out Athens' allies. Athenian hopes now rested on taking up an even more bold offensive to cut Spartan and Corinthian supplies from Sicily. In 416 B.C. Alcibiades promoted an ambitions strategic plan for conquering Syracuse, controlling all of Sicily, defeating Carthage, and then returning with greatly strengthened forces to the final defeat of a surrounded Peloponnese. The conception was brilliant, but required the undivided support of the entire Athenian polity. The democrats embraced it with enthusiasm, but as usual Nicias opposed and recommended continued traditional operations in Chalcidice. The expedition was voted and launched in June of 415, but with a fatally divided command of Alcibiades, Nicias, and the professional soldier, Lamachus. The campaign was barely begun when Alcibiades was recalled to stand trial on charges brought by his opponents, (desecrating the hermes) leaving the hopes of Athens in the hands of the chief opponent of the strategic plan. Rather than face certain execution, Alcibiades fled to Sparta! At first the campaign gained successes. Syracuse was duly invested by land and sea, but Athenian attempts to build a wall of circumvallation were blocked by a Syracusian counter wall. Lamachus was killed, the fleet was defeated, then supplies ran out, a Spartan general arrived to aid the defense, and Nicias was procrastinating as usual. A second fleet was sent under Demosthenes. But his assault in July 413 was also defeated. Demosthenes then urged a general withdrawal to Athens, but Nicias would neither advance nor retire. The Athenian fleet was blocked in the harbor and then defeated in battle. Nicias attempted to move the army inland, but it was pursued, surrounded, and finally massacred. Both generals were executed and the few "survivors" were enslaved. Peloponnesian War: Phase 4 (412-408) Sparta resumed the war officially in August 414 and all Greece expected Athens to loose. Sparta now had a strong fleet with additional reinforcements from the west. Athens had lost its best sailors and had nearly exhausted its treasury. In March 413 King Agis occupied Decelea to keep Athens in a constant blockade on the land side and cut off the Athenian silver mines. The Athenian empire soon started to fall apart with one city revolt after another in 412 and 411. Finally Persia entered the contest by authorizing its satrap in Sardis, Tissaphernes, to support Sparta. An oligarchic party seized power in Athens and started to offer surrender until blocked by a resurgence of the democratic party. Alcibiades now fled from Sparta to Sardis where he persuaded Tissaphernes to withhold his support from Sparta. The Athenian navy now recalled Alcibiades to command and resumed operations. With the grain supply from Sicily in complete Spartan control and that from Egypt blocked by the same forces, (and Persia), Athens now was totally dependent on food from Crimea through the Hellespont. There the Athenian commanders Thrasybulus and Thrasylus defeated the Spartan, Mindarus, at Cynossema in September of 411. In March of 410 Alcibiades won a great victory over the opposing navy and supporting Persian army at Cyzicus on the Sea of Marmora, giving Athens again maritime supremacy. Sparta again suggested peace, but the democrat demagogues as usual refused to listen. In 409 Alcibiades recaptured Byzantium, cleared the Bosporus and secured the grain supply. He made a triumphant return to Athens on 16 June 408, but his enemies remained unreconciled. Peloponnesian War: Phase 5 (407-404) In autumn of 408 a new Spartan admiral, Lysander, arrived at the chief naval base at Ephesus and began building a new fleet with the aid of the new Persian satrap, Cyrus. With unlimited Persian resources, he soon had a formidable force, but continued throughout 407 to refuse Alcibiades' enticements to come out for battle. Finally Alcibiades was forced to divide his own fleet due to supply shortages. Leaving one force at Notium under Antiochus to observe but with strict orders to refuse battle, Alcibiades sailed north to re-provision by plundering enemy towns. Lysander promptly sailed out and routed Antiochus. Alcibiades returned to renew the blockade but the damage was already done. His personal enemies at home were now able to force his recall. Instead, Alcibiades again fled, this time to a castle near the Hellespont. For the next year Lysander was superseded by Callicratidas, according to the Spartan legal requirement for single year appointments. Callicratidas blockaded the Athenian fleet of Conon in Mitylene harbor. Another fleet sailed from Athens and in the battle of Arginusae in August 406 the largest fleets so far seen in the war entered battle. Callicratidas was drowned while loosing and Sparta again offered peace. Again the Athenian democrats led by Cleophon refused. Even more incredible, during the course of their victory bad weather had prevented the Athenian admirals from rescuing some of their own sailors from sinking ships. The democrat party had them recalled and executed. The new generals for 405 were Alcibiades' opponents. They now moved the entire fleet up to the open beach at Aegospotami on the Asiatic side of the Hellespont. Lysander lay opposite in a good harbor at Abydos. Vainly Alcibiades went to warn his townsmen of their danger, but his opponents would not listen. In September 405 Lysander captured practically the whole Athenian fleet without a blow and thus brought the entire war to an end in one stroke. With the grain supply now cut Lysander could proceed to Athens itself to blockade it from the sea while the Spartan army under King Pausanius held the land side. After six months of starvation and no prospect for relief, Athens surrendered on generous terms offered by Sparta. Corinth and Thebes protested, demanding total destruction, but Sparta did not want to create too great a power vacuum. The city walls and those connecting Athens to Piraeus were torn down and the empire dissolved. Peloponnesian War: Bibliography Ancient sources: Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 2 vols. trans by Thomas Hobbes, ed. David Grene, 1959. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. and also the edition trans by Crawley and ed. by Sir Richard Livingstone, 1960. Oxford University Press, New York. Xenophon, Hellenica, I. II Diodorus, XII Plutarch, Lives of Pericles, Nicias, Alcibiades, and Lysander in Plutarch's Lives, Dryden Translation, The Modern Library, New York. Secondary sources Adcock, F. E. 1962. The Greek and Macedonian Art of War, University of California Press, Berkeley. Anderson, J. K. 1970. Military Theory and Practice in the Age of Xenophon, University of California Press, Berkeley. Bluhm, William T. "Casual Theory in Thucydides' Peloponnesian War", Political Studies, vol. X. Feb. 1962, Connolly, Peter, 1977. The Greek Armies, Macdonald Educational, London, England. Delbruck, Hans, 1975 Geschichte der Kriegskunst in Rahmen der Politischen Geschichte, Warfare in Antiquity - History of the Art of War vol I, trans by Walter Renfroe, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. Green, Peter, 1970. Armada from Athens, Hodder and Stoughton, London, England. Grundy, G. B. 1961 Thucydides and the History of his Age, 2nd ed. 2 Vols. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, England. Hackett, General Sir John, 1989, Warfare in the ancient World, Facts on File, New York. Hanson, Victor Davis, 1989. The Western Way of War, Alfred A. Knopf, New York. Kagan, Donald, 1987, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, Cornell University Press, Ithica, Kagan, Donald, 1987, The Archidamian War, Cornell University Press, Ithica. Kagan, Donald, 1987, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, Cornell University press, Ithica. Kagan, Donald, The Fall of the Athenian Empire, Cornell University Press, Ithica Nelson. R. B. 1973. Warfleets of Antiquity, Wargames Research Group, Sussex, England. Nelson, Richard, 1975. Armies of the Greek and Persian Wars, Wargames Research Group, Sussex, England. Rogers, William Ledyard, 1937. Greek and Roman Naval Warfare, (reprint 1977) Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. Sealey, Raphael, 1976. A History of the Greek City States 700-338 B.C., University of California Press, Berkeley. Ste. Croix, G. E. M. de, 1972. The Origins of the Peloponnesian War, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York. Strassler, Robert, ed. The Landmark Thucydides, The Free Press, NY>. 1996. Warry, John, 1995, Warfare in the Classical World, Salamander Books, NY. Prepared by AACTchJS, AAC Staff. Use of this material is protected under America Online and other copyright. Any use of this material must cite AOL's Academic Assistance Center and the author and its source. (edited by AACProfSTP)