* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Cardiovascular Risk Assessment Using Pulse

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

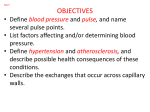

Cardiovascular Risk Assessment Using Pulse Pressure in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) Michael Domanski, James Norman, Michael Wolz, Gary Mitchell, Marc Pfeffer Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on May 7, 2017 Abstract—Increased stiffness of the conduit arteries has been associated with increased risk of death and cardiovascular death in a number of populations. None of these populations, however, are fully representative of the US population. The cohort examined in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) that was free of overt cardiovascular disease was selected to be representative of the US population. We assessed and quantified the increased risk of death associated with elevated pulse pressure in this population. A cohort of 5771 subjects from NHANES I was used to determine the value of adding pulse pressure to standard cardiovascular disease risk factors for assessment of the risk of death during a mean follow-up period of 16.5 years. Analyses were performed by use of the SUDAAN statistical package for performing Cox proportional regression, logistic regression, and other standard methods in complex, weighted samples. Pulse pressure increased with increasing age, body mass index, cholesterol level, and mean arterial pressure. With increasing pulse pressure, the percentage of cigarette smokers decreased and the percentage of diabetics increased. Despite these associations with known risk factors, pulse pressure was independently predictive of an increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and all-cause mortality. It provides independent prognostic information beyond that provided by known risk factors that were evaluated in this study, including the Sixth Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure hypertension classification. A 10 mm Hg increase in pulse pressure in persons 25 to 45 of age was associated with a 26% increase in risk of cardiovascular death (95% confidence interval [CI], 5 to 50) and with an 10% increase (95% CI, 2 to 19) in persons 46 to 77 years of age. In a cohort designed to be representative of the US population, elevated pulse pressure has been shown to provide independent prognostic information. This variable may be a marker for the extent of vascular disease and may contribute to the occurrence of clinical events. (Hypertension. 2001;38:793797.) Key Words: pulse 䡲 arteries 䡲 cardiovascular diseases I ncreased arterial stiffness, as indicated by increased pulse pressure, has been associated with an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events, including stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, cardiovascular death, and overall mortality, in a number of populations.1–11 With aging, there is a gradual stiffening of the conduit arteries that results from the loss of elastin and deposition of collagen.12 With stiffening, peak systolic pressure increases for any given flow wave. Additionally, the pulse wave velocity of the pressure pulse is increased. This results in earlier return of reflections from the periphery that, as stiffening progresses, arrive in the central aorta in late systole rather than early diastole. This contributes to an augmentation of peak systolic pressure and a reduction in diastolic pressure (and consequently an increase in pulse pressure). In addition to aging, arterial stiffening appears to be hastened by a number of conditions, including hypertension,12 menopause,13 glucose intolerance,14 elevated homocysteine levels,15 polymorphisms of the angiotensin type I receptor gene,16 and renal failure.17 Although a number of populations have been studied, none of them is fully representative of the US population as a whole. The First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) was a complex, stratified probability sample of the noninstitutionalized US population between 1 and 77 years of age.18 –20 We examined individuals in this cohort who were ⱖ25 years to determine and quantify the independent prognostic significance of pulse pressure and to determine whether pulse pressure adds prognostic information beyond that supplied by the classification of the Sixth Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI) on prognosis.21 Received March 6, 2001; first decision March 22, 2001; revision accepted April 23, 2001. From the Clinical Trials Group, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (M.D., J.N., M.W.), Bethesda, Md; and Cardiovascular Engineering Inc (G.M.) and Division of Cardiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (M.P.), Boston, Mass. Correspondence to Michael J. Domanski, MD, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Rockledge II Center, 6701 Rockledge Dr, Room 8146, Bethesda, MD 20892-7936. © 2001 American Heart Association, Inc. Hypertension is available at http://www.hypertensionaha.org 793 794 Hypertension October 2001 TABLE 1. CVD Risk Factor Means by Quartiles of Pulse Pressure Pulse Pressure Quartile, mm Hg ⱕ36 36 – 44 44 –55 ⬎55 1471 1370 1377 1553 Pulse pressure, mm Hg 31.0⫾7.7 40.7⫾3.7 49.4⫾3.7 68.5⫾15.8 Mean arterial pressure, mm Hg 92.3⫾15.3 95.5⫾14.8 98.6⫾3.8 108.9⫾23.6 䡠䡠䡠 ⬍0.00001 Systolic pressure, mm Hg 112.9⫾15.3 122.6⫾15.5 131.5⫾17.4 154.5⫾29.5 ⬍0.00001 Diastolic pressure, mm Hg 82.0⫾15.3 81.9⫾14.8 82.1⫾17.8 86.0⫾22.8 ⬍0.00001 n P* Age, y 40.2⫾11.1 42.0⫾15.2 45.4⫾13.7 54.6⫾16.5 ⬍0.00001 Body mass index, kg/m2 24.8⫾5.8 25.1⫾5.9 25.5⫾5.9 26.5 ⫾7.1 ⬍0.00001 212.4⫾61 215.8⫾59 219.1⫾56 Cholesterol, mg/dL 230.7⫾63 ⬍0.00001 Race, % black 10.2 8.5 8.9 11.6 Gender, % women 54.5 49.3 50.6 54.2 䡠 䡠 䡠† 䡠 䡠 䡠† 1.6 3.0 2.5 6.7 ⬍0.00001 45.3 42.2 40.2 37.6 ⬍0.00001 Diabetes, % Cigarette smokers, % Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on May 7, 2017 Values are mean⫾SD when appropriate. *For test of trend. †Significant curvilinear effect. Methods In 1971 to 1975, the National Center for Health Statistics conducted NHANES I. Data were collected from a complex, stratified probability sample of 23 808 individuals in the civilian noninstitutionalized US population through a variety of questionnaires and a standardized medical examination administered from mobile hospitals. Starting in 1982, the NHANES Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study was conducted to provide a database for studies on the relationship of baseline clinical, nutritional, and behavioral factors to subsequent morbidity and mortality. The study is described in detail elsewhere.22–24 There were 14 407 examinees in NHANES I who were 25 to 77 years of age at the time of the initial examination (1971 to 1975). Direct information on smoking habits at baseline was available from a subsample of 6903 of the original participants of NHANES I who were given a detailed examination. After those who were taking blood pressure medication were eliminated, a subsample of 5771 persons with all values of the variables of interest was available for our analyses. The mean length of follow-up was 16.5 years (range, 16 days to 22 years). Mortality data were collected between 1982 and 1992 by matching with the National Death Index. Causes of death were coded according to the ninth revision of the International Classification of Diseases.25 If the decedent’s code was between 390 and 459, the cause of death coded was attributed to cardiovascular disease (CVD). Coronary heart disease (CHD) was coded as 410 through 414. Of the original cohort, 96.2% of those 25 to 77 years of age were successfully traced, and death certificates were obtained from 4497 (97.7%) of the 4604 decedents. Statistical Methods The cohort in this analysis consisted of 5771 adults 25 to 74 years of age who, when appropriately weighted according to the geographic and demographic strata from which they were drawn, accurately represent the US population of the same ages. Analyses were performed with the SUDAAN statistical package,26 which contains procedures for performing Cox proportional-hazards regression, multiple linear regression, logistic regression, and other standard methods applied to complex, weighted samples. Covariates used in these analyses were the following risk factors for CVD measured or observed at baseline: gender, race (specified as black or nonblack on NHANES I data forms), diabetes, and cigarette smoking (each as binary variables), as well as age, body mass index, serum cholesterol, and mean arterial pressure calculated as one third systolic plus two thirds diastolic blood pressure. The JNC VI classification of blood pressure for adults ⱖ18 years of age21 was also used. We assigned ordinal scale values of 1 to 5 to the respective categories of optimal, normal but not optimal, high normal, stage 1 hypertension, and stage 2 or higher hypertension. Quartiles of pulse pressure were calculated with the NHANES detailed sample weights, which produced unequal numbers of subjects in the 4 groups of our analysis cohort but represent equal numbers of persons in the United States. For the same reason, the approximate median age at baseline of 45 years divides the cohort into 2 groups of unequal size. Tests for trend in mean risk factor values across pulse pressure quartiles were made with linear regression for continuous valued factors and logistic regression for the binary factors (race, gender, smoking, and diabetes). All Cox proportional-hazards regression survival analyses are reported in terms of hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Pulse pressures and mean arterial pressures are expressed in units of 10 mm Hg. Results Known risk factors for CVD were assessed as a function of quartile of pulse pressure (Table 1). Increasing pulse pressure is associated with increasing age, body mass index, cholesterol level, and mean arterial pressure; an increasing percentage of diabetics; and fewer cigarette smokers. The percentages of blacks and women display significant U-shaped distributions. A Cox regression analysis, adjusted for the influence of known CVD risk factors, including mean arterial pressure level, assessed the effect of pulse pressure on overall mortality, CVD mortality, and CHD mortality. Tables 2 through 4 display the results of these multivariate analyses. Pulse pressure is significantly associated with total mortality in patients above the median age of 45 years and with CVD and CHD mortality in patients of all ages. Pulse pressure was most strongly associated with the risk of CHD death (Table 4). Mean arterial pressure is associated with total and CVD death in all ages and with CHD death in patients ⱖ46 years of age. Pulse pressure is not associated with an increase in non-CVD. Compared with persons of other races, blacks are at increased risk for death from all causes and for death as a result of CVD but not of CHD. No evidence was found of an Domanski et al Pulse Pressure and Cardiovascular Risk Assessment TABLE 2. Survival Analysis: Hazard Ratios for All Deaths by Age Group 795 TABLE 4. Survival Analysis: Hazard Ratios for CHD Deaths by Age Group Age Group Age Group 25– 45 y All 25– 45 y 46 –77 y People, n 2566 3205 People, n 2566 3205 Deaths, n 174 1319 Deaths, n 38 342 CVD risk factor CVD risk factor Age (per 10 y) 1.09 (1.05–1.14) 1.10 (1.09–1.12) Age (per 10 y) 1.19 (1.09–1.31) Race (black vs nonblack) 2.01 (1.29–3.16) 1.36 (1.08–1.72) Race (black vs nonblack) 0.50 (0.18–1.37) 1.11 (1.09–1.14) 0.66 (0.43–1.01) Gender (women vs men) 0.52 (0.36–0.74) 0.67 (0.58–0.78) Gender (women vs men) 0.30 (0.12–0.68) 0.45 (0.33–0.62) Diabetes 3.52 (1.78–6.98) 1.49 (1.01–2.21) Diabetes 6.89 (2.68–17.71) 1.88 (1.09–3.23) Cigarette smoking 1.46 (1.18–1.81) 1.51 (1.37–1.67) Cigarette smoking 1.26 (0.75–2.10) 1.52 (1.29–1.79) BMI (per kg/m2) 1.01 (0.97–1.06) 1.01 (0.99–1.03) BMI (per kg/m2) 1.04 (0.96–1.12) 1.07 (1.04–1.09) Cholesterol (per 10 mg/dL) 1.05 (1.00–1.10) 1.01 (0.99–1.03) Cholesterol (per 10 mg/dL) 1.08 (0.99–1.17) 1.05 (1.01–1.09) MAP (per 10 mm Hg) 1.18 (1.01–1.39) 1.12 (1.06–1.20) MAP (per 10 mm Hg) 1.22 (0.98–1.51) 1.15 (1.02–1.29) Pulse pressure (per 10 mm Hg) 1.09 (0.95–1.26) 1.07 (1.01–1.13) Pulse pressure (per 10 mm Hg) 1.44 (1.22–1.70) 1.15 (1.03–1.28) Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on May 7, 2017 BMI indicates body mass index; MAP, mean arterial pressure. Values in parentheses are 95% CIs. interaction between pulse pressure and gender or between pulse pressure and race in the analyses of CVD deaths in the either age group. Table 5 presents the results of a Cox regression analysis of cardiovascular disease mortality with mean arterial pressure replaced by the JNC VI classification with the 5 levels described above. It shows that pulse pressure retains its prognostic significance for cardiovascular death in persons of all ages. An increase in pulse pressure of 10 mm Hg in persons ⱕ45 years of age produces an estimated increase in the risk of CVD death of 24%; the same increase in persons ⬎45 years of age predicts an increase in risk of 12%. Discussion This analysis assesses the significance of pulse pressure on the risk of death in a cohort of patients that is specifically TABLE 3. Survival Analysis: Hazard Ratios for CVD Deaths by Age Group Age Group 25– 45 y 46 –77 y People, n 2566 3205 Deaths, n 60 613 CVD risk factor Age (per 10 y) 1.15 (1.08–1.22) 1.11 (1.10–1.13) Race (black vs nonblack) 1.51 (0.70–3.27) 1.07 (0.81–1.43) Gender (women vs men) 0.33 (0.17–0.65) 0.61 (0.47–0.78) Diabetes 5.95 (2.03–17.42) 1.69 (1.11–2.56) Cigarette smoking 1.49 (1.02–2.18) 1.44 (1.25–1.66) 1.02 (1.00–1.05) 2 BMI (per kg/m ) 1.04 (0.98–1.10) Cholesterol (per 10 mg/dL) 1.12 (1.04–1.22) 1.02 (1.00–1.05) MAP (per 10 mm Hg) 1.41 (1.15–1.74) 1.23 (1.12–1.35) Pulse pressure (per 10 mm Hg) 1.26 (1.05–1.50) 1.10 (1.02–1.19) Abbreviations as in Table 2. Values in parentheses are 95% CIs. Abbreviations as in Table 2. Values in parentheses are 95% CIs. designed to be representative of the US population. It demonstrates that pulse pressure is associated with an increased risk of all-cause, CVD, and CHD death independent of mean arterial pressure but not with death from noncardiovascular causes. Furthermore, it provides a quantitative estimate of the hazard ratios in the US population. Interestingly, blacks are at greater risk for all-cause mortality than persons of other races, a finding that appears to be based solely on non-CHD deaths. In this cohort, they did not appear to be at increased risk for death from CHD. By including the JNC VI classification as a covariate in a Cox regression model with pulse pressure and the other CVD risk factors, we have demonstrated that pulse pressure has prognostic significance independent of the JNC VI classification. A general approach to risk assessment in any data set using blood pressure is improved by including both systolic and diastolic pressures. Because of the equivalence of the information conveyed by either mean arterial and pulse pressures or systolic and diastolic blood pressures, the use of either pair in any regression model results in identical values of the statistical measure of fit of the models. Although systolic blood pressure is a major prognostic determinate, the inclusion of information from diastolic or pulse pressure (which is systolic minus diastolic blood pressure) may add prognostic information, depending on the database examined. Systolic pressure includes substantial contributions from both the steady-flow (mean arterial) and pulsatile (pulse pressure) components of hemodynamic load. Our model includes mean arterial and pulse pressures, which incorporate systolic and diastolic pressures. This analysis suggests that pulse pressure determination may prove useful in further refining the assessment of prognosis. Comparison With Other Studies A number of studies in diverse cohorts support the notion that pulse pressure carries important, independent prognostic information. An analysis of data from the Hypertension 796 Hypertension October 2001 TABLE 5. Survival Analysis: Hazard Ratios for CVD Deaths by CVD Risk Factor and Age Group with JNC VI Classification of Blood Pressure for Adults Age Group CVD Risk Factor 25– 45 y 46 –77 y People, n 2566 3205 Deaths, n 60 613 CVD risk factor Age (per 10 y) 1.16 (1.09–1.23) 1.11 (1.09–1.12) Race (black vs nonblack) 1.71 (0.87–3.37) 1.16 (0.87–1.55) Gender (women vs men) 0.37 (0.20–0.71) 0.60 (0.47–0.78) Diabetes 5.76 (2.00–16.61) 1.65 (1.07–2.56) Cigarette smoking 1.49 (1.02–2.17) 1.44 (1.24–1.66) 2 Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on May 7, 2017 BMI (per kg/m ) 1.04 (0.98–1.10) 1.03 (1.01–1.05) Cholesterol (per 10 mg/dL) 1.12 (1.04–1.20) 1.02 (1.00–1.05) JNC VI (per unit increase in scale) 1.61 (1.15–2.26) 1.22 (1.08–1.38) Pulse pressure (per 10 mm Hg) 1.24 (1.06–1.46) 1.12 (1.03–1.21) Abbreviations as in Table 2. Values in parentheses are 95% CIs. The JNC VI ordinal scale is as follows: 1 ⫽ optimal; 2 ⫽ normal, not optimal; 3 ⫽ high normal; 4 ⫽ stage 1 hypertension; and 5 ⫽ stage 2 or higher hypertension. Detection Follow-Up Program reported by Abernathy et al27 incorporated other available cardiovascular risk factors into a logistic regression model, demonstrating that pulse pressure is a significant predictor of mortality in that cohort. In 1989, Darne et al8 reported their study of 27 000 French subjects in whom pulse pressure was associated with cardiovascular death independent of other known risk factors, including diastolic and mean arterial pressures. Madhavan et al6 studied 2207 hypertensive patients in a union-sponsored hypertension control program. In this study, an elevated pretreatment pulse pressure was associated with adverse cardiovascular events. Fang et al7 examined data on 5730 participants who entered a hypertension control program between 1973 and 1992. After 5.4 years of follow-up, an elevated pulse pressure was identified as the most important predictor of a subsequent myocardial infarction. Domanski et al5 showed an association between pulse pressure and the risk of stroke in patients entered in the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). Using a proportional-hazards model, they demonstrated an 11% increase in the risk of stroke and a 16% increase in total mortality for each 10 mm Hg increase in pulse pressure. Patients entered in the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) trial were also studied.2 For the 2231 post– myocardial infarction patients in the trial (left ventricular ejection fraction ⱕ0.40), multivariate analysis showed pulse pressure to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality and myocardial infarction. Patients entered in the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) study, who had left ventricular ejection fraction ⱕ0.35, were shown on multivariate analysis to have a strong association of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular death with pulse pressure.1 In fact, in this study, an increase in mean arterial pressure was associated with reduced mortality, whereas an increase in pulse pressure was associated with increased mortality. Across a wide spectrum of diseases from severe hypertension to heart failure with lowered mean arterial pressure, an elevated pulse pressure was found to be an indicator of heightened CVD risk. Chae et al3 followed 1621 healthy elderly subjects with no history of heart failure and a mean age of 77.9 years for an average of 3.8 years. After adjustment for other CVD risk factors, pulse pressure was shown to be independently associated with the risk of developing heart failure. Data from 50 years of follow-up of participants in the Framingham study demonstrated that pulse pressure, rather than systolic or diastolic pressure, had the strongest association with mortality.4 Although Framingham comprises an initially healthy cohort of adults in an eastern Massachusetts city, the design of NHANES I provides a population that is representative of the US population. Pathophysiology Associated With Increased Conduit Vessel Stiffness There are a number of potential mechanisms by which increased arterial stiffness could worsen prognosis. The loading caused by increased vascular stiffness has been shown to be associated with increased left ventricular mass.28 –30 Increased pulse pressure is also associated with increased intimal and medial thickness of the carotid artery.31–33 Data from animal studies suggest that the ventricle is more susceptible to ischemia when the aorta is stiff34,35 and that coronary occlusion results in greater ventricular damage.36 Although the presence of atherosclerosis may increase arterial stiffness, increased stiffening occurs even in populations in which atherosclerosis is unusual, as demonstrated by the work of Avolio et al11 in China. It is possible that aortic stiffening may be atherogenic. In a primate model, atherosclerosis severity was found to increase with an increase in pulsatile strain.37 In addition, increased pulse pressure has been associated with reduced NO production by the endothelium,38 which has been shown to be atherogenic.39 It should be added that pulse pressure changes may occur with changes in stroke volume. Thus, an elevated pulse pressure should be viewed as both a marker of vascular disease and a contributor to disease progression. Study Limitations Caution must be exercised in the interpretation of models of mortality in survey data based on death certificates. The causes of death listed on death certificates are not always accurate.40 However, they are useful in establishing trends and have been shown to track well with studies of mortality that used more accurate methods of ascertainment.41 Because the white-coat effect may raise initial blood pressures measured in the office setting,42 a single measurement can overestimate blood pressure levels. Multiple measurements reduce the variability of the measurements.43 Clinical Implications and Conclusions This study demonstrates and quantifies the prognostic importance of pulse pressure in a cohort that is representative of the US population. Because there is a functional component of Domanski et al Pulse Pressure and Cardiovascular Risk Assessment arterial stiffening, conduit vessel stiffening is a potential therapeutic target. The demonstration that pulse pressure adds prognostic information beyond that of known CVD risk factors, including the JNC VI classification, suggests that it may be useful as an additional factor in risk assessment for future therapeutic decision making. References Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on May 7, 2017 1. Domanski M, Mitchell G, Norman J, Exner D, Pitt B, Pfeffer M. Independent prognostic information provided by sphygmomanometrically determined pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:951–958. 2. Mitchell G, Moye L, Braunwald E, Rouleau J, Bernstein V, Geltman E, Flaker G, Pfeffer M. Sphygmomanometrically determined pulse pressure is a powerful predictor of recurrent events after myocardial infarction in patients with impaired left ventricular function. Circulation. 1997;96: 4254 – 4260. 3. Chae C, Pfeffer M, Glynn R, Mitchell G, Taylor J, Hennekens C. Increased pulse pressure and risk of heart failure in the elderly. JAMA. 1999;281:634 – 639. 4. Franklin SS, Khan SA, Wong ND, Larson MG, Levy D. Is Pulse Pressure Useful in Predicting Risk for Coronary Heart Disease? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;100:354 –360. 5. Domanski M, Davis B, Pfeffer M, Kastantin M, Mitchell G. Isolated systolic hypertension: prognostic information provided by pulse pressure. Hypertension. 1999;34:375–380. 6. Madhavan S, Ooi W, Cohen H, Alderman M. Relation of pulse pressure and blood pressure reduction to the incidence of myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 1994;23:395– 401. 7. Fang J, Madhaven S, Cohen H, Alderman M. Measures of blood pressure and myocardial infarction in treated hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 1995;13:413– 419. 8. Darne B, Girerd X, Safar M, Cambien F, Guize L. Pulsatile versus steady component of blood pressure: a cross-sectional analysis and a prospective analysis of cardiovascular mortality. Hypertension. 1989;13:392– 400. 9. Benetos A, Safar M, Rudnichi A, Smulyan H, Richard J, Ducimetiere P, Guize L. Pulse pressure: a predictor of long-term cardiovascular mortality in a French male population. Hypertension. 1997;30:1410 –1415. 10. Benetos A, Rudnichi A, Safar M, Guize L. Pulse pressure and cardiovascular mortality in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 1998;32:560 –564. 11. Avolio A, Clyde K, Beard T, Cooke H, Ho K, O’Rourke MF. Improved arterial distensibility in normotensive subjects on a low salt diet. Arteriosclerosis. 1986;6:166 –169. 12. Benetos A, Laurant S, Asmar A, Lacolley P. Large artery stiffness in hypertension. J Hypertens. 1997;15(suppl 2):S89 –S97. 13. Rajkumar C, Kingwell B, Cameron J, Waddell T, Mehra R, Christophidis N, Komesaroff P, McGrath B, Jennings G, Sudhir K, Bart A. Hormonal therapy increases arterial compliance in post-menopausal women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:350 –356. 14. Salomaa V, Riley W, Kark J, Nardo C, Folsom A. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and fasting glucose and insulin concentrations are associated with arterial stiffness indexes: the ARIC study. Circulation. 1995; 91:1432–1443. 15. Sutton-Tyrrell K, Bostom A, Selhub J, Zeigler-Hohnson C. High homocysteine levels are independently related to isolated systolic hypertension in older adults. Circulation. 1997;96:1745–1749. 16. Benetos A, Gautier S, Ricard S, Topouchian J, Asmar R, Poirier O, Larosa E, Guize L, Safar M, Soubrier F, Cambien F. Influence of angiotensin II type 1 receptor gene polymorphism on aortic stiffness in normotensive and hypertensive patients. Circulation. 1996;94:698 –703. 17. Blacher J, Guernia A, Pannier B, Marchais S, Safir M, London G. Impact of aortic stiffness in end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 1999;99: 2434 –2439. 18. National Center for Health Statistics. Plan and Operation of the Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 1971–1973. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1979.Vital Health Stat [1] No. 10a, DHEW Publication No. (HSM) 73–1310. 19. National Center for Health Statistics. Plan and Operation of the Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 1971–1973. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1979.Vital Health Stat [1] No. 10b, DHEW Publication No. (HSM) 73–1310. 797 20. National Center for Health Statistics. Plan and Operation of the NHANES I Augmentation Survey of Adults 25–74 Years, United States, 1974 –75. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Vital Health Stat [1] No. 14, DHEW Publication No. (PHS) 78 –1314. 21. The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Bethesda, Md: NIH; 1997. Publication No. 4080. 22. Cohen B, Barbano H, Cox C, Feldman J, Finucane F, Kleinman J, Madans J. Plan and operation of the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study, 1982–1984. Vital Health Stat 1 1987;22:1–142. 23. Cox C, Rothwell S, Madans J, Finucane F, Fried V, Kleinman J, Barbano H, Feldman J. Plan and operation of the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study, 1987. Vital Health Stat 1.1992;27:1–190. 24. Cox C, Mussolino M, Rothwell S, Lane M, Golden C, Madans J, Feldman J. Plan and operation of the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study, 1992. Vital Health Stat 1. 1997;35:1–231. 25. World Health Organization. Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death: Based on the Recommendations of the Ninth Revision Conference, 1975, and Adopted by the Twenty-Ninth World Health Assembly, Volumes 1 and 2. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1977. 26. Shah B, Barnwell B, Bieler G. SUDAAN User’s Manual, Release 7.5. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1997. 27. Abernathy J Borhani N, Hawkins C, Crow R, Entwisle G, Jones J, Maxwell H, Langford H, Pressel S. Systolic blood pressure as an independent predictor of mortality in the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program. Am J Prev Med. 1986;12:23–32. 28. Isnard R, Panier B, Laurent S, London G, Diebold B, Safar M. Pulsatile diameter and elastic modulus of the aortic arch in essential hypertension: a noninvasive study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:399 – 405. 29. Gardin J, Arnold A, Gottdeiner J, Wong N, Fried L, Klopfenstein H, O’Leary D, Tracy R, Kronmar R. Left ventricular mass in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Hypertension. 1997;29:1095–1103. 30. Gatzka C, Cameron J, Kingwell B, Dart A. Relation between coronary artery disease, aortic stiffness, and left ventricular structure in a population sample. Hypertension. 1998;32:572–578. 31. Franklin S, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Bella S, Weber M, Kuller L. The importance of pulsatile components of hypertension in predicting carotid stenosis in older adults. J Hypertens. 1997;10:1143–1150. 32. Matthews K, Owens J, Kuller L, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Lassila H, Wolfson S. Stress-induced pulse pressure change predicts women’s carotid atherosclerosis. Stroke. 1998;29:1525–1530. 33. Bots M, Hofman A, Grobbee D. Increased common carotid intima-medial thickness: adaptive response of reflection of atherosclerosis? Findings from the Rotterdam Study. Stroke. 1997;28:2442–2447. 34. Watanabe H, Ohtsuka S, Kakihana M, Sugishita Y. Coronary circulation in dogs with an experimental decrease in aortic compliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:1497–1506. 35. Buckberg G, Fixler D, Archie J, Hoffman J. Experimental subendocardial ischemia in dogs with normal coronary arteries. Circ Res. 1972;30: 67– 81. 36. Kass D, Saeki A, Tunin R, Recchia F. Adverse influence of systemic vascular stiffening on cardiac dysfunction and adaptation to acute coronary occlusion. Circulation. 1996;93:1533–1541. 37. Lyon R, Runyon-Hass A, Davis H, Glagov S, Zarins C. Protection from atherosclerotic lesion formation by reduction of artery motion. J Vasc Surg. 1987;5:59 – 67. 38. Ryan S, Waack B, Weno B, Heistad D. Increases in pulse pressure impair acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation. Am J Physiol. 1995;268: H359 –H363. 39. Drexler H. Endothelium as a therapeutic target in heart failure. Circulation. 1998;98:2652–2655. 40. Lloyd-Jones DM, Martin DO, Larson MG, Levy D. Accuracy of death certificates for coding coronary heart disease as the cause of death. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1020 –1026. 41. Lenfant C, Friedman L, Thom T. Fifty years of death certificates: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1066 –1067. 42. Mancia G, Grassi G, Pomidossi G, Bertinieri G, Parati G, Ferrari A, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure measurement by the doctor on patients’ blood pressure and heart rate. Lancet. 1983;2:695– 698. 43. Canner Pl, Borhani No, Oberman A, Cutler J, Prineas RJ, Langford H, Hooper J. The Hypertension Prevention Trial: assessment of the quality of blood-pressure measurements. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:379 –392. Cardiovascular Risk Assessment Using Pulse Pressure in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) Michael Domanski, James Norman, Michael Wolz, Gary Mitchell and Marc Pfeffer Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on May 7, 2017 Hypertension. 2001;38:793-797 doi: 10.1161/hy1001.092966 Hypertension is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 2001 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0194-911X. Online ISSN: 1524-4563 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://hyper.ahajournals.org/content/38/4/793 Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Hypertension can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Hypertension is online at: http://hyper.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/