* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download sample - Create Training

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

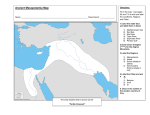

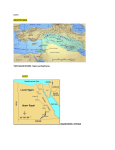

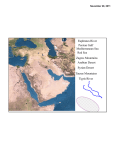

HANDBOOK TO LIFE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA SELECTED BOOKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR Art and the Romans: A Study of Roman Art as a Dynamic Expression of Roman Character (Lawrence, Kans.: Coronado Press, 1975) The Conflict of Generations in Ancient Greece and Rome (Amsterdam: Grüner, 1976) Doorways Through Time: The Romance of Archaeology (Los Angeles and New York: Jeremy Tarcher and St. Martin’s Press, 1986) Hyperculture: The Human Cost of Speed (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1998) Cultural Amnesia: America’s Future and the Crisis of Memory (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2000) Climbing Olympus: The Inspiring Power of Greek Myth (Naperville, Ill.: Sourcebooks, 2003) HANDBOOK TO LIFE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA STEPHEN BERTMAN University of Windsor Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia Copyright © 2003 by Stephen Bertman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bertman, Stephen. Handbook to life in ancient Mesopotamia / Stephen Bertman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4346-9 1. Iraq—Civilization—To 634. I. Title. DS69.5 .B47 2002 935—dc21 2002003516 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Cathy Rincon Cover design by Semadar Megged Printed in the United States of America VB Hermitage 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION x LIST OF MAPS xi LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS xi 1 GEOGRAPHY OF MESOPOTAMIA The Land and Its Rivers Natural Resources Surrounding Countries Gazetteer Reading 1 2 4 5 6 37 2 ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY The Discoverers Dating the Past Digging for History Ancient Narratives Survey of History Key Rulers of Mesopotamia Reading 39 40 49 51 54 54 58 59 GOVERNMENT AND SOCIETY The Structure of Civilization The Stratification of Society The Beginnings Kingship Taxation Justice and Law 61 62 62 63 63 67 68 3 Biographies of Political Leaders Reading 72 111 4 RELIGION AND MYTH The Multiplicity of the Gods The Governance of the World The Names and Functions of the Gods Myths Places of Public Worship Priests and Priestesses Holy Days and Festivals Divination and Exorcism Personal Piety The Concept of Immortality Reading 113 114 115 115 126 127 128 130 132 133 134 135 5 LANGUAGE, WRITING, AND LITERATURE Language The Great Decipherments Major Languages Writing Literature Reading 137 138 138 142 144 149 182 ARCHITECTURE AND ENGINEERING Building Materials and Houses Domestic Architecture Techniques of Construction From Village to City 185 186 188 190 191 viii 6 Temples Ziggurats Palaces City Planning Walls Canals and Aqueducts Bridges Roads Reading 191 194 198 201 202 203 207 209 210 7 SCULPTURE AND OTHER ARTS The Role of the Artist Materials Sculpture Pottery Painting Mosaic Glass Cylinder Seals Carved Ivory Jewelry Reading 213 214 214 214 223 224 226 229 231 236 237 241 8 ECONOMY Definition and Structure Significance Farming and Animal Husbandry Fishing and Hunting Crafts Professions Wages and Prices Reading 243 244 244 244 247 248 248 248 250 TRANSPORTATION AND TRADE Transportation by Water Transportation by Land Trade Weights and Measures Reading 251 252 253 255 257 258 MILITARY AFFAIRS The Influence of Geography Evidence Fortifications Weapons and Equipment The Organization of the Army 261 262 262 262 263 265 9 10 Siege Warfare Psychological Warfare The Art of War Ancient Monuments and Modern Warfare Reading 267 267 268 270 271 11 EVERYDAY LIFE Work Slavery Marriage and Family Birth, Death, and the Belief in an Afterlife Homes Clothing Cosmetics and Perfume Food and Drink Music Toys and Games Sports Education Health and Medicine Reading 273 274 274 275 281 285 288 291 291 294 298 300 300 304 309 12 MESOPOTAMIA AND SACRED SCRIPTURE The Old Testament Mesopotamia and the Apocrypha Mesopotamia and the New Testament Mesopotamia and the Koran Reading 311 312 322 322 323 323 THE LEGACY OF MESOPOTAMIA Continuity and Change Inspiration and Imagination An Enduring Legacy Detroit of the Chaldees Twin Legacies Reading 325 326 332 334 335 336 337 13 CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE 339 LIST OF MUSEUMS WITH MAJOR MESOPOTAMIAN COLLECTIONS 342 BIBLIOGRAPHY 343 INDEX 377 “Y’ know—Babylon once had two million people in it, and all we know about ’em is the names of the kings and some copies of wheat contracts and . . . the sales of slaves. Yes, every night all those families sat down to supper, and the father came home from his work, and the smoke went up the chimney, —same as here.” — Thornton Wilder, Our Town ACKNOWLEDGMENTS W. Hallo, Angeline Sturam, and Dr. Fred Wassermann, and to Diana Wu, Margie Prytulak, and Biljana Barisic for giving my manuscript electronic form. I am also indebted to the following individuals for assisting me in obtaining photographic illustrations: Carla Hosein, Sylvia Inwood, Tory James, Ryan Jensen, Ulla Kasten, and Charles Kline. Ultimately, my greatest debt is to those who are now nameless but were human like ourselves, those whose long-ago hopes and dreams still swirl in the dust of Iraq. In writing this book, it is with those ancient ghosts I seek to keep faith, for to be remembered is to be alive. F or rescuing the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia from oblivion we are indebted to generations of travelers and explorers, archaeologists and philologists, whose love of the past gave that past new life and whose words and work inspired and shaped this book. I remain personally indebted to Leonard Cottrell and others whose popular books on archaeological discovery pointed the way for me when I was young, and to the teachers—Jotham Johnson, Casper J. Kraemer Jr., Lionel Casson, and Cyrus Gordon—I was later lucky to find as guides. For this project, special thanks for bibliographical help go to Elaine Bertman, William H A N D B O O K T O L I F E I N A N C I E N T M E S O P O TA M I A viii In Memory of Cyrus H. Gordon (1909–2001) who looked across artificial borders and bravely reported a wider truth INTRODUCTION builders; the farmers, merchants, and artisans who lived out their daily lives; the scribes who told their story in the world’s oldest writing; and the works of literature that still survive that speak of a search for meaning in a land that so often saw the hopes of humankind frustrated by nature’s raw power or man’s voracious greed. Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia presents a panorama of human striving painted on a broad geographical and historical canvas, a story of the struggle to create civilized life in a fertile land racked by brutal conquest, a tale of universal human aspirations written in the dust and recaptured by archaeology. In retelling this tale the author has produced English versions of ancient texts designed to convey their underlying humanity. In the main, yesterday’s Mesopotamia is today’s Iraq, a war-torn land where people still struggle to eke out their daily lives as did their ancestors thousands of years ago. Yet buried in Iraq’s barren desert there also lie the ruins of an earlier glory and splendor that once shone for all to see. A long with Egypt, ancient Mesopotamia was the birthplace of civilization. But, unlike Egypt, Mesopotamia was the home of not one but a succession of glorious civilizations—the civilizations of Sumer, Babylonia, and Assyria—that together flourished for more than three millennia from about 3500 to 500 B.C.E. It was Sumerian mathematicians who devised the 60-minute hour that still rules our lives. It was Babylonian architects who designed the fabled Tower of Babel and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the “Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.” And it was Assyrian kings and generals who, in the name of imperialism, conducted some of the most ruthless military campaigns in recorded history. The civilizations of Mesopotamia are united by many common denominators: the land of the twin rivers—the Tigris and Euphrates—and the resources it possessed; the gods and goddesses that lorded over it; the cities—the world’s first—that rose and fell with their towers and temples; the lawmakers and empire- H A N D B O O K T O L I F E I N A N C I E N T M E S O P O TA M I A x LIST OF MAPS The Ancient Near East Cities of Mesopotamia Babylon 3 9 13 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Euphrates River Excavations at Babylon Excavations at Babylon Reconstruction of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate Babylon’s Ishtar Gate (façade) Arch at Ctesiphon Ziggurat at Dur-Kurigalzu Sargon’s Palace at Dur-Sharrukin Restored View of Kalhu (Nimrud) View of Ur Ziggurat at Ur Ruins of Borsippa Sketching sculptures at Nineveh Workmen at Nineveh Temple entrance at Kalhu (Nimrud) Passageway at Nineveh Excavation at Kuyunjik Tunnel at Kuyunjik Portrait of Layard Transporting a winged bull Arrival of an Assyrian lion Portrait of Ashurnasirpal II Assyrian king Code of Hammurabi Code of Hammurabi (closeup) Coin of Alexander the Great Ashurbanipal and his queen Portrait of Ashurnasirpal Inscribed cylinder of Cyrus the Great Stele of Esarhaddon Portrait of Gudea Boundary stone Relief portraying Naram-Sin Portrait of Sargon the Great Sennacherib on his throne Chariot of Tiglathpileser III Relief of Tiglathpileser III Ur-Nanshe the builder Ninurta opposes a monster Marduk as a dragon 2 11 12 14 14 16 17 18 23 34 35 40 41 41 42 43 44 44 45 46 L I S T O F M A P S A N D I L L U S T R AT I O N S xi 46 64 67 69 69 75 78 79 82 85 86 93 98 101 102 106 107 109 114 121 Reconstruction of the ziggurat at Ur Model of a sheep’s liver Portrait of Grotefend The Behistun Rock Portrait of Rawlinson Development of cuneiform Clay tablet and stylus Cuneiform tablet and envelope The hero Gilgamesh Code of Hammurabi Brickmaking Reed houses Portrait of Gudea as builder Restored view of Babylon Ziggurat at Ur Restored view of Sennacherib’s palace Interior of Assyrian palace Exterior of Assyrian palace Votive statuettes from Tell Asmar Statue of Gudea Sumerian assault Assault on an enemy city Attack on fortifications Wounded lions Winged lion Transporting a stone bull Pawprints of a dog Glazed tile Bull from the Ishtar Gate Dragon from the Ishtar Gate Seal-stones Cylinder seal impression Ivory heads Woman in a window Man mauled by a lioness Jewelry of Queen Puabi Royal cup-bearer Assyrian delicacies A sow and her young Lion hunt Lion gnawing a chariot wheel Transporting cargo by kelek Groom and horses The metropolis of Babylon Assyrian soldiers and equipment Armed Assyrian soldiers Soldiers in a chariot Archers and a battering ram Scribes tallying heads Royal Standard of Ur (battle) Royal Standard of Ur (celebration) Assyrian homecoming Couple in bed Sumerian husband and wife Infant burial Child beside sarcophagus Burial ceremony at Ur Reed hut Brick home Assyrian sandals Courtiers drinking Assyrian orchestra Assyrian musician Great Lyre from Ur Great Lyre from Ur (detail) Children’s toys Game-board from Ur Flood tablet Flood Pit at Ur Black Obelisk Black Obelisk (detail) Jewish captives from Lachish Bull of Nineveh Architectural fragments 127 133 139 140 141 146 147 147 154 167 187 189 193 194 195 199 200 200 217 218 219 220 221 221 222 222 223 227 228 228 232 234 236 236 237 240 240 H A N D B O O K T O L I F E I N A N C I E N T M E S O P O TA M I A xii 245 246 247 248 253 255 263 263 264 266 267 268 269 269 270 279 280 282 282 283 286 287 291 292 295 296 296 297 298 300 315 316 318 319 319 331 337 1 GEOGRAPHY OF MESOPOTAMIA mental horizons were limited to the names of the cities and kingdoms where they lived. Today, most of ancient Mesopotamia lies within the borders of modern Iraq, with some parts—to the west and north—in Syrian and Turkish territory. The rivers that defined Mesopotamia were the Tigris and the Euphrates. Like the name Mesopotamia itself, the spelling of the rivers’ names is something we owe to the Greeks. The original name of the Tigris was the Idiglat; the original name of the Euphrates, the Buranum— names that were first used by the inhabitants of the land in prehistoric times and which survive in their earliest records. In the Bible, the Tigris was called the Hiddekel, the Hebrew pronunciation of the river’s authentic name, while the Euphrates was simply called the Prat. The book of Genesis describes them as two of the four rivers that flowed out of Eden and watered its famous garden. Biblical tradition thus connects Mesopotamian geography with the beginnings of the human race. The river valleys of Mesopotamia are framed by the desert, the mountains, and the sea. To the west is the Syrian Desert; to the north and east, the mountains of Turkey and Iran; to the south, the Persian Gulf. Rising in the mountains, the rivers descend through foothills and steppe and flow toward the southeast through a flat, alluvial plain until they empty through marshes into the sea. Reading as we do from left to right, upon hearing the phrase “Tigris and Euphrates,” we may think of the Tigris as the one farther west. In actually, the Euphrates lies to the west and the Tigris to the east. Of the two rivers the Euphrates is the longer (about 1,740 miles in length) compared to the Tigris (about 1,180 miles). Each is fed by tributaries: the Euphrates by the Balikh and Khabur Rivers; the Tigris, by the Great Zab, the Little Zab, and the Diyala. THE LAND AND ITS RIVERS It was ancient Greek travelers and historians who first gave the land the name by which we know it: Mesopotamia. The name means “the land between the rivers” (from mesos, the Greek word for “between” or “in the middle”; potamos, the Greek word for “river”; and ia, a suffix that the Greeks attached to the names of places). The ancient Mesopotamians did not have a name for the whole land; instead, their 1.1 A century-ago view of the Euphrates River from a point south of the site of ancient Babylon. (Robert William Rogers, A History of Babylonia and Assyria, 6th ed. [New York: Abingdon Press, 1915]) H A N D B O O K T O L I F E I N A N C I E N T M E S O P O TA M I A 2 Black Sea HITTITE PHRYGIA Caspian Sea KINGDOM URARTU A n a t o l i a MITANNI CYPRUS eni e so SYRIA p o ta m . Pho R. PERSIA ASSYRIA sR Mediterranean Sea M i Tigr cia Euph rat es Nineveh ia Baghdad LURISTAN Babylon ISRAEL Palestine AKKAD BA JUDAH SUMER B YL ELAM EGYPT O N IA Ur N 0 0 150 150 300 Miles 300 Kilometers Persian Gulf Map 1. The Ancient Near East the rivers along with the sea’s own retreat pushed the coastline south. When the winter snows in the mountains melted (sometime between April and early June), the rivers flooded unpredictably and often violently, destroying everything in their path. Their propensity for destructive fury and the uncertainty of their will, it is argued, draped much of Mesopotamian thought in pessimism. On the other hand, it was their Today, in the south, the Tigris and Euphrates merge into the Shatt al-Arab before jointly emptying into the sea; but in ancient times they flowed into the Persian Gulf separately. In those days (during the fourth and third millennia B.C.E.) the Gulf extended as much as 150 miles farther inland than it does today, making ancient cities like Ur and Eridu (inland today) virtual seaports. Over the centuries, heavy accumulations of silt deposited by G E O G R A P H Y O F M E S O P O TA M I A 3 life-giving waters—channeled by the technology of irrigation—that made urban civilization possible in the flood-prone plain. Yet even when the rivers were not guilty of shortterm caprice, their long-term behavior could undermine everything that civilization had built: an otherwise vital city could literally be left high and dry economically when a meandering river altered its course and cut it off from trade and transportation. In the steppe to the north, life was less erratic. There the rivers coursed through a rocky terrain that made their paths more permanent. Unlike the subtropical south where summer temperatures could average 120°F., the climate in the north was temperate. There rainfall, rather than artificial irrigation, watered farmers’ fields and sustained their livestock. Indeed, from the wild grains that grew in the north, agriculture itself may have begun. Yet the south was the more fertile land, thanks to the richness of its alluvial soil, a richness that—when watered—could support large population centers and material prosperity. The geographic differences between north and south—between Assyria in the north and Babylonia in the south—bred differences in temperament between their peoples and generated political division and tension. At times, greed or vindictiveness ignited war. Meanwhile, there were also ethnic differences within the south. In the deepest south lived the Sumerians, who created the world’s first civilization. Though the Sumerians were united by a common language and common traditions, the control of the lands and waterways inspired intercity rivalries and war. To their north dwelt the Semitic Akkadians, who coveted what the Sumerians possessed and conquered them, joining Sumer to Akkad. With the rise of the city and kingdom of Babylon, the whole of the south came to be called Babylonia. Babylon, Babylonia’s largest city, lay on the Euphrates; Nineveh, Assyria’s largest city, on the Tigris. Baghdad, Iraq’s modern capital, is situated midway down the Tigris at the point where it veers closest to the Euphrates. The name “Mesopotamia” is, in fact, a misnomer: many of the land’s ancient cities were located not between the two rivers but just outside the edge of the irregular spearpoint they form as they aim southeast to the sea. NATURAL RESOURCES Mesopotamia’s major resources were its water and fertile soil. If, as the ancient Greek historian Herodotus claimed, Egypt was the gift of the Nile, Mesopotamia was the gift of the Tigris and Euphrates. This was especially true of the alluvial plain to the south, where the well-watered fertility of the land nurtured such staples of the people’s diet as barley, sesame, and dates. From riverine clay the Mesopotamians not only made bricks but also fashioned clay tablets to write on with the help of pens cut from the reeds that grew along the rivers’ banks. A unique resource of the land was bitumen, a natural asphalt that seeped from beds in the ground, especially in the area around Hit on the Euphrates. Bitumen had many uses: as an adhesive for bricks, as a waterproof coating in construction, and as a cement to create works of art. The critical resources that Mesopotamia largely lacked were building stone (except in Assyria where gypsum was available), construction-grade timber, and minerals, including copper and tin (needed to make bronze), iron, silver, and gold. Combined with the demands of an increasingly affluent society and the desires of its rulers for splendor, the scarcity of these resources encouraged foreign trade and the rise of a merchant class as the Mesopotamians H A N D B O O K T O L I F E I N A N C I E N T M E S O P O TA M I A 4 ture, for example), but are offset by equally striking differences in style and intent. About five centuries after the earliest civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia arose, yet another civilization was born, the civilization of the Indus Valley, represented by the ruined cities of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa. Artifacts and inscriptions point to commercial contact between Mesopotamia and this land, which the Mesopotamians called Meluhha. Whether the contact was more than commercial we cannot yet say. In the second and first millennia B.C.E., the imperialistic ambitions of the Assyrians and Babylonians brought them into military conflict with an array of other nations that vied for the control of the lands known today as Syria and Israel. These lands were important because of the trade routes that passed through them and the tribute that could be exacted from their cities. During the second millennium B.C.E. Egypt fought for the control of this region against two other superpowers: the Hittites, who were based in Turkey, and the Mitanni, who occupied northwestern Mesopotamia. By the first millennium B.C.E. direct strikes were made against cities in ancient Israel by Assyrian and Babylonian armies. Assyrian armies went so far as to invade Egypt, and a Babylonian army under Nebuchadnezzar captured Jerusalem and took Jewish prisoners of war back to Babylon. The emotional turmoil of these times resonates in the writings of the Hebrew prophets and the biblical book of Lamentations. By the sixth century B.C.E., the armies of Babylon were defeated by a new player that had stepped on the stage of world politics, the Persians, who were to amass the largest empire the world had ever seen, one that stretched from Turkey in the west to India in the east and south into Egypt. The kings of Persia even invaded Greece, but they were valiantly exchanged agricultural produce and textiles for the commodities they lacked. As a result, caravans plied regular overland trade routes throughout the Middle East and ships sailed up and down the Persian Gulf. Timber was hauled in from the Zagros Mountains and Lebanon; copper and tin from Anatolia, the Caucasus, and Iran; silver from the Taurus Mountains; and gold from Egypt and even India. From Afghanistan came a precious blue mineral called lapis lazuli. Ships were sailing as early as the fifth millennium B.C.E. between Mesopotamia and ports in Bahrain and Oman, and as early as the third millennium B.C.E. between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. So great was the influence of Babylonian merchants that their Akkadian language and cuneiform script became tools for international commercial and diplomatic correspondence throughout the ancient Near East. SURROUNDING COUNTRIES As we have seen, commerce brought Mesopotamia into contact with other lands, both near and far. At almost the same time that civilization was born in Sumer (near the end of the fourth millennium B.C.E.), it also was born to the west in Egypt, land of the Nile. Indeed, scholars still debate where it was born first. And when Sumer’s monarchs were later laid in their graves surrounded by their royal retinues and splendor, the pyramids of Egypt’s pharaohs were just being built. How much these two classic eras of civilization knew of each other’s existence is likewise a subject for debate. Striking cultural parallels between them exist (their nearly simultaneous invention of writing and monumental architec- G E O G R A P H Y O F M E S O P O TA M I A 5 we visited each of these cities and listened to their tales. rebuffed there in a series of battles fought in the early fifth century B.C.E. In the late fourth century B.C.E. a charismatic leader named Alexander the Great led an army of Macedonian and Greek soldiers in a war against Persia fought for revenge and greater glory. After defeating the Persians, Alexander made Babylon the capital of his new empire, seeking to create a new multicultural society on a global scale, one in which the European heritage of Greece would be blended with the legacy of the Orient. Though Alexander died before he could see his dream fulfilled, the forces he set into motion brought West and East closer together than they had ever been before, or would ever be again. Evidence of over three millennia of cultural development and change lie buried in the cities of the ancient Tigris and Euphrates. It is time Original Name GAZETTEER Names of Cities Listed below in alphabetical order are the names of ancient sites in Mesopotamia that have special archaeological and historical significance. Where the original name of a site is known, it is listed alphabetically; where only the modern name of its ruins survive, the modern name appears in its stead. In cases where a Mesopotamian city is mentioned in the Bible, the biblical spelling of its name is provided as well. Modern Name Biblical Name Abu Salabikh Adab Tell Bismaya Agade Akkad Akshak Tell Mujeilat Arbil Erbil Ashur Qalat Shergat Babil(a) Babylon Bad-tibira Tell Madain Borsippa Birs Nimrud Carchemish Jerablus Asshur (=Assyria) Babel Carchemish Chagar Bazar Choga Mami Ctesiphon Tell al-Ma’aridh (?) Dilbat Tell Dulaim Dur-Katlimmu Sheikh Hamid Dur-Kurigalzu Aqar Quf & Tell al-Abyad Dur-Sharrukin Khorsabad H A N D B O O K T O L I F E I N A N C I E N T M E S O P O TA M I A 6 Original Name Modern Name Biblical Name Dura-Europos Eridu Abu Shahrain Eshnunna Tell Asmar Girsu Tello Guzana Tell Halaf Hatra Al-Hadr Imgur-Enlil Balawat Isin Ishan Bahriyat Jemdet Nasr Kalhu Nimrud Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta Telul al-Aqar Kish Tell Ingharra & Tell Uhaimir Kutha Tell Ibrahim Lagash Tell al-Hiba Calah Larak Larsa Tell Senkereh Mari Tell Hariri Neribtum Tell Ishchali Nina-Sirara Zurghul Ninua Kuyunjik & Tell Nebi Yunus Nippur Nuffar Nuzu (Nuzi) Yorghun Tepe Puzrish-Dagan Drehem Nineveh Qalat Jarmo Samarra Shaduppum Tell Harmal Shubat-Enlil Tell Leilan Shuruppak Fara Sippar Tell Abu Haba Sippar-Amnanum (Sippar-Anunitu) Tell ed-Der Tell Arpachiyeh Tell Brak Tell Fakhariyeh Tell Hassuna Tell al-Oueili Tell Qalinj Agha G E O G R A P H Y O F M E S O P O TA M I A 7 (continues) (continued) Original Name Modern Name (Karana or Qatara?) Tell al-Rimah Biblical Name Tell es-Sawwan Tell Taya Tell al-Ubaid Tell Uqair Tepe Gawra Terqa Tell Ashara Til Barsip Tell Ahmar Tuttul Tell Bi’a Tutub Khafaje Umm Dabaghiyah Umma Ur Tell Muquayyar Uruk Warka Erech Yarim Tepe Descriptions of Cities temple complex, the archaeologists unearthed some 500 fragments of clay tablets inscribed in cuneiform. Among them were portions of literary works: the character-building advice of a father to his son (called “The Instructions of Shuruppak”) and a hymn praising the temple of the Sumerian mother-goddess Ninhursag. Abu Salabikh Abu Salabikh contains the remains of a city that flourished in the fourth and third millennia B.C.E. In antiquity, the city was situated on a branch of the Euphrates, about halfway between the ancient cities of Kish and Nippur in the southern part of Mesopotamia known as Sumer. Its original name may have been Kesh, a Sumerian city whose patron goddess was Nisaba, the goddess of the reeds that grew abundantly in the riverbanks and marshes. Because the reeds were used by scribes to make their pens, Nisaba was their patron deity as well. Today, the ruins of the city lie about 75 miles southeast of Baghdad. Abu Salabikh was first excavated in the 1960s. The excavations uncovered the oldest city walls that have ever been found in southern Mesopotamia, the land where the world’s first cities arose. In what may have once been a Adab This Sumerian city once lay on the ancient path of the Euphrates River, 25 miles southeast of Nippur. When the river changed its course, the city began to die. Today its ruins are called Tell Bismaya. Agade Around 2300 B.C.E., the Semitic king Sargon conquered Sumer and made the city of Agade his capital. There he built his palace and erected temples to honor the gods of war, Ishtar and Zababa. For over a century, Agade served as the seat of an empire whose reach extended to Iran in the east and Syria in the H A N D B O O K T O L I F E I N A N C I E N T M E S O P O TA M I A 8 Tepe Gawra Tell Arpachiyah Dur-Sharrukin 50 100 Kilometers N Nineveh Mosul Tell Qalinj Agha Lake Van Carchemish Guzana Gr Tell Fakhariyeh tZ ea Gr Imgur-Enlil Kalhu ab SINJAR MTS . Arbil Mosul tle Lit R. IN MR HA SYRIA Samarra Tell es-Sawwan Choga Mami Z AG RO S Eshunna M TS . Shaduppum Dur-Kurigalzu la Euphrate s R. S. MT . Dura-Europos Dura-Europos Mari Nuzu sR IRAQ Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta i Tigr Terqa Qalat Jarmo Kirkuk iya Kh ab u r Tell al-Rimah Umm Dabaghiyah Hatra Dur-Katlimmu Dur-Katlimmu Ashur IRAN . Z ab R R. Yarim Tepe D Chagar Bazar Tuttul Tutub Neribtum Ctesiphon Akshak Sippar-Amnanum Sippar Jemdet Nasr Kutha Babylon Kish Abu Salabikh Borsippa Nippur Tell Uqair Puzrish-Dagan Dilbat Isin Adab Umma Girsu Shuruppak Lagash Bad-tibira Nina-Sirara Tell al-Oueili Uruk Larsa Ur Tell al-Ubaid Eridu Baghdad Modern cities Ancient cities a spi Ca Black Sea nS ea IRAQ Mediterranean Sea t R. Til Barsip ea Shubat-Enlil Tell Brak Tell Hassuna ris R. Tig Tell Taya . 0 100 Miles bR 50 Za 0 Basra IRAN SYRIA Persian Gulf Persian Gulf Red Sea Map 2. Cities of Mesopotamia G E O G R A P H Y O F M E S O P O TA M I A 9 A canal, partly underground, was engineered by King Sennacherib in the seventh century B.C.E. to supply the city with more water. Ishtar, the goddess of love and war, was revered here from early times. In later times, Arbil became famous because of a battle that was fought in 331 B.C.E. at nearby Gaugamela, when Alexander the Great defeated Darius III, king of the Persians. Alexander’s decisive victory there (in the so-called Battle of Arbela) marked the end of the Persian Empire and the beginning of the Hellenistic Age. west. Agade prospered from imperialism, and foreign ships bearing exotic cargo docked in its harbor. Historians call Sargon’s native land Akkad, from the Hebrew spelling of the city’s name (Genesis 10:10). Likewise, the Semitic language of its people is called Akkadian. A later form of this language was spoken by the Babylonians and Assyrians, and for a time became an international language of commerce and diplomacy. About 2200 B.C.E. the city and its empire fell to an invading horde called the Guti, who swept in from the Zagros Mountains of Iran. According to a poem entitled “The Curse of Agade,” the city’s destruction was the consequence of divine vengeance because Sargon the Great’s grandson, King Naram-Sin, had desecrated a temple. In fulfillment of the divine curse, the city’s freshwater turned to salt, and its lands were abandoned. The gods must have been forgiving, however, if Babylonian inscriptions are to be believed, for Babylon’s kings were constructing buildings there as late as the sixth century B.C.E. To the frustration of archaeologists and historians, the ruins of Agade have never been located. Perhaps the curse of the gods is still in effect after all. Ashur Called Qalat Sherqat today, the ruins of Ashur lie on a plateau high above the Tigris in northern Iraq, about 60 miles south of the modern city of Mosul. In ancient times it lay on a caravan route that connected the Levant with Iran, and prospered from its location. Though the site had been explored by Europeans as early as 1821, scientific excavation did not commence until the beginning of the 20th century under the direction of the German archaeologist, Walter Andrae. In the second millennium B.C.E., Ashur became the first royal capital of the Assyrian nation. Its name was the same as the country’s name as well as the name of the country’s divine protector, the god Ashur. The names “Assyria” and “Syria” still echo this name. Even when the Assyrian Empire’s political capital was moved (to Kalhu, Dur-Sharrukin, and Nineveh), Ashur remained its religious capital and the last resting place of its kings. In 614 B.C.E., the city was sacked by the Medes and Babylonians, who simultaneously brought to an end Assyria’s dreams of imperial glory. At its height, Ashur boasted 34 temples. The oldest, indeed the oldest public building in the entire city, was the temple of Ishtar, goddess of both war and love. In its ruins, archaeologists found a carving of a naked woman on a bed, and erotic images fashioned from lead and dedicated by worshipers whose Akshak Forty miles north of Babylon lay the northern Akkadian city of Akshak, later called Opis. In 539 B.C.E., Cyrus, king of Persia, met and defeated the Babylonian army here before going on to capture Babylon itself. The Greek historian Herodotus reports that when a white horse belonging to Cyrus drowned in the nearby Tigris, Cyrus punished the river by draining off its water. Today the remains of Akshak are known by the name of Tell Mujeilat. Arbil Arbil was a major Assyrian city located in the country’s heartland between the Great and Little Zab Rivers, tributaries of the Tigris. H A N D B O O K T O L I F E I N A N C I E N T M E S O P O TA M I A 10 sexual powers had been restored by the goddess’ intervention. The city’s patron god Ashur was also honored with a temple as well as with a nearby ziggurat, a lofty stepped platform surmounted by a shrine. In addition to religious structures, the city contained two palaces, an old and a new. In their basements in vaulted tombs, the monarchs were laid to rest in stone sarcophagi together with their treasure. None of their riches were to escape the hands of plunderers. Babil(a) See Babylon Babylon Babylon is the most renowned city of ancient Mesopotamia and one of the most famous urban centers of antiquity. Despite its ruined state, Babylon retained a permanent place in Western consciousness because of its role in the Bible. It was the site of the Tower of Babel, scriptural symbol of humanity’s hubris, as well as the internment site for the pious Hebrew captives who were marched into exile by King Nebuchadnezzar II in the sixth century B.C.E. In addition, it was described with eyewitness detail by the “father of history,” Herodotus, and it was home to the “Hanging Gardens,” one of the legendary Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Today, the remains of Babylon are spread out over a cluster of mounds, or tells, located on the Euphrates about 59 miles southwest of Baghdad. Early European travelers were drawn to the locale by accounts of the city’s former glory, by the extent of its ruins, and by the presence—there and nearby—of architectural remains that suggested the fabled tower. Some returned to Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries with artifacts, including the very first samples of cuneiform writing. Excavations did not begin in earnest, however, until the 19th century. The major expedition, which lasted from 1899 to 1914, was directed by German archaeologist Robert Koldewey. 1.2 During Koldewey’s excavation of Babylon, a basket brigade clears rubble from the site. (Rogers, A History of Babylonia and Assyria, 1915) The name Babylon is itself a bit of a mystery. The biblical Hebrews traced its origins to a word in their own language (bavel) that meant “confusion,” deriving the name of the tower from the linguistic confusion God visited upon its builders so they could no longer communicate to complete their work (an explanation, incidentally, for how the world’s many languages came into being). In the Semitic language of the Babylonians themselves, the name of their city may have meant “Gate of God” or “Gate of the Gods” (bav il or bav ilim). But the real root and its true meaning may even antedate the Babylonians, and perhaps their Sumerian predecessors as well. G E O G R A P H Y O F M E S O P O TA M I A 11