* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Table of Contents

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

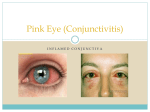

Table of Contents 1.0 The lacrimal system o 1.1 The dry eye 1.1.1 BUT test o 1.2 The watering eye o 1.3 Infection of the lacrimal passages 2.0 Conjunctivitis in the older child and adult o 2.1 Bacterial conjunctivitis o 2.2 Viral conjunctivitis 2.2.1 Herpes simplex keratitis o 2.3 Other infective keratitis o 2.4 Allergic conjunctivitis 3.0 Episcleritis 4.0 Subconjunctival haemorrhage 5.0 Other disorders that may lead to red eye References 1.0 The lacrimal system The following section details some common disorders of the lacrimal system. [ top ] 1.1 The dry eye The main lacrimal gland produces about 95% of the aqueous component of tears. The remaining 5% is produced by the accessory lacrimal glands. Tears serve various necessary functions in the eye. These include lubrication, antibacterial action and oxygenation. The precorneal tear film has three layers; an outer lipid layer; a middle aqueous layer; and an inner mucin layer. The three layers have different functions but they all contribute to the properties of the tear film. Three separate factors are also necessary for adequate surfacing of the cornea by precorneal tear film: 1. a normal blink reflex 2. congruity between the external ocular surface and the eyelids 3. normal epithelium. Symptoms of dry eye include irritation, foreign body sensation, stringy mucus, transient blurring of vision. Less commonly, itching, photophobia and a tired, heavy feeling of the eyelids may be present. Practice Tip! Few patients suffering from dry eyes will actually complain that their eyes are dry. The tear film break-up time (BUT) test is a simple method of assessing tear film integrity. [ top ] 1.1.1 BUT test 1. 2. 3. 4. Instill fluorescein into the lower fornix, taking care not to touch the cornea. Instruct the patient to blink several times and then refrain from blinking. Scan the eye with a cobalt blue light source. After a short time , black spots or lines, which indicate the formation of dry spots, will appear on the tear film. The BUT is the time between the last blink and the formation of the first dry spot. Dry spots that repeatedly form in the same location should be ignored because this is most likely indicative of a local epithelial defect rather than instability of the precorneal tear film. 5. A BUT of less then 10 seconds is considered abnormal. Treatment of dry eye includes artificial tear drops and ointments. Referral to an ophthalmologist is recommended for chronic cases of dry eyes in which the underlying cause is not known. [ top ] 1.2 The watering eye There are two main causes of excessive eye watering. They are: 1. lacrimation from reflex hypersecretion due to corneal/conjunctival irritation 2. obstructive epiphora as a result of failed tear drainage. This may be due to mechanical obstruction of the drainage system or lacrimal pump failure. A comprehensive history is important in distinguishing the two main causes of excessive eye watering. Excessive bilateral watering associated with itching, irritation, a foreign body sensation and photophobia is indicative of reflex hypersecretion due to corneal/conjunctival irritation. In contrast to this, the watering due to obstructive epiphora is usually unilateral and not associated with ocular irritation. Medications, such as systemic 5-fluorouracil, may cause punctal stenosis and hence obstructive epiphora. Previous history of Bell's palsy may also suggest lacrimal pump failure. External inspection is also important. Inspect the eyelids for evidence of ectropion, trichiasis, eversion of the lower punctum. Inspect the medial canthal area for enlargement of the lacrimal sac which may result from dacryocystitis, mucocele or a tumour. Palpate and apply pressure over the lacrimal sac. If mucopurulent material refluxes, a mucocele due a lacrimal obstruction is indicated. If pressure on the lacrimal sac causes pain, dacryocystitis is indicated. Instil fluorescein dye into both conjunctival sacs. If lacrimal drainage is normal, very little dye will be visible with a cobalt blue light after 2 minutes. Prolonged retention of dye is indicative of impaired lacrimal drainage. Caution! Diagnosis of obstructive epiphora should result in ophthalmological referral. [ top ] 1.3 Infection of the lacrimal passages Canaliculitis Canaliculitis can be either acute or chronic. A chronic infection causes discharge and a raised punctum with concretions in the canaliculus. Patients suspected of canaliculitis should be referred to an ophthalmologist. Dacryocystitis Dacryocystitis (infection of the lacrimal sac) is quite rare and is usually associated with a blockage of the nasolacrimal duct. Acute infection is managed with antibiotic treatment and warm compresses. Irrigation and probing are contraindicated. [ top ] 2.0 Conjunctivitis in the older child and adult After the tear film, the conjunctiva is the most important defensive barrier of the eye. For this reason it is susceptible to a variety of infections, inflammations and insults. The following section outlines some of the disorders of the conjunctiva and their consequent treatment. [ top ] 2.1 Bacterial conjunctivitis This is the commonest type of conjunctivitis seen in childhood. Bacterial conjunctivitis causes a purulent discharge and is almost invariably bilateral by the time the doctor is consulted. The organisms responsible are usually respiratory pathogens such as Pneumococcus or Haemophilus. In severe cases, there may be a pseudomembrane on the tarsal conjunctiva. Most cases are self limiting but treatment is recommended because conjunctivitis is contagious and complications such as corneal infection, although rare, are potentially disastrous. Children with acute conjunctivitis should be kept away from school. Patients should be reminded to wash their hands after touching their eyes. If the clinical diagnosis is certain, culture is unnecessary unless there are grounds to suspect a virulent organism such as Gonococcus or if the conjunctivitis is particularly severe. First-line treatment, as suggested by the Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic [1], is either chloramphenicol 0.5% eye drops or combination drops polymyxin B sulfate + neomycin sulfate + gramicidin (Neosporin), in a dose of 1 to 2 drops hourly decreasing to 6-hourly as the infection improves. Ointment can be used instead of drops at bedtime. Note that chloramphenicol should not be used for more than a few days at a time as bone marrow suppression, although rare after eye drops, can occur with long-term use. Ciprofloxacin (Ciloxan) or framycetin (Soframycin) are acceptable alternatives. Other useful antibiotics include fluroquinolones, sulfacetamide and erythromycin. Be sure the patient/parent knows how to instil the drops. If there is no significant improvement after three days of treatment, either the wrong drug is being used or the diagnosis is wrong. Propamidine drops 0.1% (Brolene) can be used for very mild cases, in a dose of 1 to 2 drops, 3 to 4 times daily for 5 to 7 days. [ top ] 2.2 Viral conjunctivitis The signs which distinguish viral from bacterial conjunctivitis are that the discharge is mucoid or muco-purulent rather than frankly purulent and in viral conjunctivitis there is frequently an enlarged, tender pre-auricular lymph node present on the affected side. Viral conjunctivitis frequently begins unilaterally and may be associated with a concomitant upper respiratory tract infection. A wide variety of viruses have been implicated and include adenovirus and herpes simplex virus. In the case of Adenovirus types 8 and 19 secondary involvement of the cornea is common within a few days. Adenovirus keratoconjunctivitis may take several months to resolve. Treatment of viral conjunctivitis is symptomatic; use lubricant drops to relieve discomfort. Most cases are self limiting and last 14-21 days. The use of antibiotic-steroid combination drops has no place in the management of bacterial or viral conjunctivitis. [ top ] 2.2.1 Herpes simplex keratitis Recurrent herpes simplex infection can cause severe and potentially blinding corneal damage. The typical dendritic ulcer can be identified with Rose Bengal stain. Specific management is required (aciclovir ointment), as well as ulcer debridement. Post-herpetic problems, such as stromal keratitis and disciform keratitis, may require ophthalmic input. In the immune compromised patient (including the severely atopic), atypical and more extensive herpes simplex virus can be a problem. Bilateral corneal disease, geographic ulcers and corneal melts are among the complications of HSV in the immunocompromised and require prompt ophthalmic attention. [ top ] 2.3 Other infective keratitis Fungal and amoebic corneal infections can arise, especially associated with trauma or contact lens wear. Such infections require prompt ophthalmic review. A red eye in the contact lens wearer should produce a high level of clinical suspicion, either for severe bacterial keratitis (potentially sight threatening), or acanthamoeba. An exaggerated allergic reaction, lens over wear and lens intolerance are also possibilities. [ top ] 2.4 Allergic conjunctivitis This is more common in the adult and may be associated with hay fever or asthma. The eyes are itchy and irritable and there may only be excessive tearing or a stringy discharge. Inspection of the tarsal conjunctiva may reveal numerous small papillae (areas of oedema surrounding dilated capillaries). Vernal conjunctivitis This is the most severe form of allergic conjunctivitis and is characterised by much larger papillae than those seen in the milder forms of allergic conjunctivitis. It is usually seen in late childhood or early adolescence. There is a seasonal incidence with the disease being most severe in spring and summer. There is usually a history of asthma, eczema, hay fever or hives. The symptoms are extreme itchiness and mucoid discharge which is often described as stringy or ropy. Photophobia may become prominent if the cornea is affected. Giant papillae will be seen, especially under the upper lid, where they have a flat topped, `cobblestone' appearance. Gelatinous papillae may be seen at the limbus. The papillae under the upper lid may attain such a size as to interfere with corneal function causing the formation of an oval shaped, superiorly located corneal ulcer. Vision may be severely affected as corneal scarring often follows. The disease usually burns itself out by the late teens. There is an association between vernal conjunctivitis and the development of keratoconus (conical cornea) in the later years. Treatment of allergic conjunctivitis Combinations of naphazoline and antazoline or pheniramine drops are available over the counter and provide some remedy for the seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. These preparations provide decongestant action as well as antihistamine effects. Systemic antihistamines are sometimes necessary. In a severe acute attack, vasoconstrictors (e.g. 1/8% phenylephrine) and ice packs may be necessary. Olopatadine is a new drug used for both the treatment of acute seasonal allergic conjunctivitis and prevention of further episodes of acute seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. It has a dual action, being a selective H1 receptor-antagonist and a mast cell stabiliser. This translates to a rapid onset as well as a long duration of action (up to 12 hours). It is well tolerated. Results of an unpublished study [2] have suggested the superior efficacy and safety profile of olopatadine as compared with a topical steroid, loteprednol, for the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Topical steroids are a first line treatment for vernal conjunctivitis. Due to the risks associated with long term topical steroid use (e.g. glaucoma and cataract), maintenance is best achieved using mast cell histamine release inhibitors (e.g. cromoglycate or lodoxamide drops) if possible. Given the risk/benefit profile of the treatment of vernal conjunctivitis, referral of patients with vernal conjunctivitis to an ophthalmologist is appropriate. Desensitisation has not been shown to be an effective treatment. Golden Rule! Because of the risks associated with long term topical steroid use, such as glaucoma and cataract, the advice of an ophthalmologist should be sought when managing vernal conjunctivitis. [ top ] 3.0 Episcleritis Episcleritis presents as a sore eye with a localised red patch due to inflammation of the subconjunctival tissues. There is no discharge and treatment involves simple oral analgesics as needed. Discomfort usually subsides over a few days. [ top ] 4.0 Subconjunctival haemorrhage Subconjunctival haemorrhage occurs suddenly (eg after a bout of coughing) and is largely painless. It presents as a bright red patch that clears over a week or so, turning yellow before it fades away. This condition requires no treatment but checking the blood pressure of the patient is advised. Other bleeding problems or bruising in the clinical history should also be investigated. [ top ] 5.0 Other disorders that may lead to red eye It should be noted that many other diseases may lead to red eye and hence be associated with the external eye. In addition to the conditions listed previously, acute glaucoma (typically angle cosure) and uveitis of any form (acute endogenous, post-operative or due to penetrating eye injuries), should also be considered. [ top ] References 1. Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic, 11th Edn, 2000, Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, Melbourne. 2. Berdy G. J., Stoppel J.O., Epstein A. B. 'Comparison of the clinical efficacy and safety of olopatadine hydrochloride 0.1% ophthalmic solution and loteprednol etabonate 0.2% ophthalmic suspension in the conjunctival allergen challenge model.' (unpublished) 3. Kanski, J.J., 1989, Clinical Ophthalmology - A Systematic Approach, Butterworth & Co. Hong Kong 4. Keeney, A.H., 1976, Ocular Examination - Basis and Technique, The C.V Mosby Company. Saint Louis 5. Bradford, C. A., 1999, Basic ophthalmology for medical students and primary care residents, 7th ed., American Academy of Ophthalmology. San Francisco, CA 6. Gaston, H. 1989, 'Managing the red eye', Practitioner, vol. 22, no. 233, pp. 1566-72