* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Oral health-related quality of life and orthodontic treatment seeking

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

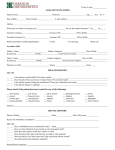

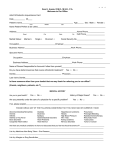

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Oral health-related quality of life and orthodontic treatment seeking Daniela Feu,a Branca Helo!ısa de Oliveira,b Marco Antônio de Oliveira Almeida,c H. Asuman Kiyak,d and José Augusto M. Miguele Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and Seattle, Wash Introduction: The aim of this study was to assess oral health-related quality of life (OHQOL) in adolescents who sought orthodontic treatment. A comparison between these adolescents and their age-matched peers who were not seeking orthodontic treatment provided an assessment of the role of OHQOL in treatment seeking. Methods: The sample consisted of 225 subjects, 12 to 15 years of age; 101 had sought orthodontic treatment at a university clinic (orthodontic group), and 124, from a nearby public school, had never undergone or sought orthodontic treatment (comparison group). OHQOL was assessed with the Brazilian version of the short form of the oral health impact profile, and malocclusion severity was assessed with the index of orthodontic treatment need. Results: Simple and multiple logistic regression analysis showed that those who sought orthodontic treatment reported worse OHQOL than did the subjects in the comparison group (P \0.001). They also had more severe malocclusions as shown by the index of orthodontic treatment need (P 5 0.003) and greater esthetic impairment, both when analyzed professionally (P 5 0.008) and by selfperception (P \0.0001). No sex differences were observed in quality of life impacts (P 5 0.22). However, when the orthodontic group was separately evaluated, the girls reported significantly worse impacts (P 5 0.05). After controlling for confounding (dental caries status, esthetic impairment, and malocclusion severity), those who sought orthodontic treatment were 3.1 times more likely to have worse OHQOL than those in the comparison group. Conclusions: Adolescents who sought orthodontic treatment had more severe malocclusions and esthetic impairments, and had worse OHQOL than those who did not seek orthodontic treatment, even though severely compromised esthetics was a better predictor of worse OHQOL than seeking orthodontic treatment. (Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010;138:152-9) T here is increasing recognition that oral disorders can have a significant impact on physical, social, and psychological well-being.1-5 This has resulted in greater clinical focus on improving quality of life as a major objective of dental care for dental conditions that are not life threatening.2,4-6 The importance of evaluating oral health-related quality of life (OHQOL) among orthodontic patients relates to the impact of dental esthetics on social a Specialist in Orthodontics, Department of Orthodontics, Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. b Associate professor, Department of Preventive and Community Dentistry, Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. c Chairman, Department of Orthodontics, Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. d Professor, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery; adjunct professor, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle. e Associate professor, Department of Orthodontics, Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The authors report no commercial, proprietary, or financial interest in the products or companies described in this article. Reprint requests to: Daniela Feu, R Moacir Avidos, no 156/apto 804, Praia do Canto, Vitória, E.S., Cep: 29055-350; e-mail, [email protected]. Submitted, May 2008; revised and accepted, September 2008. 0889-5406/$36.00 Copyright ! 2010 by the American Association of Orthodontists. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.09.033 152 acceptance and self-concept. It has been shown that those with malocclusion can develop feelings of selfconsciousness and shame about their dental condition or feel shy in social contexts, and also their body selfconcept because of facial appearance might be negatively affected.2,7-11 Nevertheless, a malocclusion can be perceived differently by the affected person,4,12,13 and a person’s self-awareness of the malocclusion might not be related to its severity.12,14,15 Therefore, when evaluating the impact of a malocclusion, it is important to consider the different domains that can be affected and their relationships to personality traits and psychosocial factors. Some people with a severe malocclusion are satisfied with or indifferent to their dental esthetics, whereas others are concerned about minor irregularities.16,17 Assessing the effect of oral disorders and conditions on quality of life can be of great value to researchers, health planners, and oral health care providers.18,19 Several instruments have been designed to measure dental outcomes in terms of the impact on quality-oflife of changes in oral health. Among these, the oral health impact profile (OHIP) and its short form American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Volume 138, Number 2 (OHIP-14) are widely used. The original 49-item OHIP was developed by Slade and Spencer,20 based on the OHQOL conceptual model of Locker,21 derived from the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps. It was designed to be applied to diverse oral conditions. The items in the original 49-item version and in the short form, OHIP-14, are grouped into 7 domains: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap.20,22 The OHIP and the OHIP-14 were originally developed for use with elderly patients, but both have been successfully used to measure the impact of oral problems in adolescents in the United States,23 Brazil,2,24,25 Myanmar,26 and Chile.27 The Brazilian version of OHIP-1419,28 has shown good psychometric properties, similar to those of the original instrument, when tested in young women19 and in 12-year-old schoolchildren.24 The aims of this study were to assess OHQOL in Brazilian adolescents aged 12-15 who sought orthodontic treatment in the Department of Orthodontics at Rio de Janeiro State University in Brazil and to measure the impacts of malocclusion severity, esthetic impairment, sex, age, and socioeconomic status on their OHQOL. A comparison between these adolescents and age-matched peers who were not seeking orthodontic treatment provided an assessment of the role of OHQOL in treatment seeking. MATERIAL AND METHODS Permission to undertake the survey was obtained from the Ethics Research Committee of Rio de Janeiro State University. Parents received a letter describing the study and requesting consent for their children to participate. The sample consisted of 225 adolescents (ages, 12-15 years) divided into 2 groups: the orthodontic group and the comparison group. All 101 children between 12 and 15 years of age who were scheduled for orthodontic treatment evaluation in the Department of Orthodontics of Rio de Janeiro State University in 2006 were eligible to participate in the orthodontic group. Because 9 parents did not allow their children to participate in the study (8.8% loss; 77.7% girls, 22.3% boys), the orthodontic group had a final number of 92 children. The comparison group initially comprised all 124 age-matched children from a public school near the university clinic. Their parents were sent a questionnaire, attached to the consent form, asking whether their children had already sought or undergone orthodontic treatment. Twenty-two children Feu et al 153 were excluded because they did not return the consent form or reported having had or sought orthodontic treatment. Therefore, the comparison group consisted of 102 children (17.7% of loss; 63.4% girls, 36.6% boys). This sample size was sufficient to estimate a prevalence of oral impacts of 25% in the comparison group and a difference between this group and the orthodontic group, with a power of 80% at a significance level of 0.05.16 Data on variables and their measurement were collected through interviews, self-completed questionnaires, and dental screenings performed by an orthodontist (D.F.). The questionnaires included a measurement of OHQOL, the Brazilian shortened version of the OHIP-14.19 During the interviews, a measurement of socioeconomic status was used, the Brazil economic classification criteria.29 This classifies people into 5 socioeconomic categories according to the educational level of the head of the household, consumer goods owned (eg, VCRs, DVDs, color TVs), and access to household help. For our statistical analysis, the 5 socioeconomic categories were divided into high (A and B) and low (C-E) social classes. After the children were interviewed and had finished filling out the questionnaires, clinical examinations were conducted to assess orthodontic treatment need and dental health status. Malocclusion severity and orthodontic esthetic impairment were measured by using, respectively, the dental health component (DHC) and the aesthetic component (AC) of the index of orthodontic treatment need (IOTN).30 Esthetic impairment, measured by IOTN-AC was also evaluated by the children themselves (AC self-perception). Dental health status was determined with the decayed, missing and filled teeth index (DMFT) and the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria.31 Students in the comparison group were examined in their school’s dental office, under conditions similar to those at the university where the orthodontic group was examined, and by the same orthodontist. The examiner had been determined as being trained in the use of the IOTN index by a researcher (gold standard) with broad experience with this occlusal index (J.A.M.). The gold standard had been previously determined for IOTN assessment during a course at the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom. The training process included examination of 20 plaster casts by both the examiner and the researcher, and subsequent comparison of their results. To assess intraexaminer reliability, 26 children were reinterviewed and reexamined 7 to 10 days after the first assessments (15 from the comparison group and 11 from the orthodontic group). 154 Feu et al Statistical analysis The data were analyzed by using software (version 7.0, StataCorp, College Station, Tex). Simple and multiple stepwise regression analyses, as well as chi-square and t tests, were used to evaluate the effects of esthetic impairment, malocclusion severity, sex, age, and socioeconomic status on OHQOL. Significance levels were set at 0.05. Kappa statistics were used to test the consistency between the examiner’s scores and the gold standard scores, and for intraexaminer reliability. To test the stability and internal consistency of the OHIP-14, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and the Cronbach reliability coefficient a were used, respectively. For OHIP-14 analysis, ordinal responses were coded from 0 for ‘‘never’’ to 4 for ‘‘very often,’’ and all 14 ordinal responses were summed to produce an overall OHIP score that could range from 0 to 56, with higher scores indicating poorer OHQOL. IOTN-AC scores range from 1 to 10 and for analytical purposes; subjects with scores greater than 5 were considered to have an esthetic orthodontic treatment need. For the DHC scores (range, 1-5), subjects with scores greater than 3 were considered to have an objective orthodontic treatment need. These determinations of orthodontic treatment needs were based on the cutoff points for index dichotomization of Mandall et al,14 which had been used in previous studies.14,32-34 RESULTS For both the DHC (kappa, 0.70) and the AC (kappa, 0.68) components of the IOTN, the examiner had good agreement with the gold standard. Intraexaminer reliability was very good (kappa, 0.98 for AC [95% CI, 0.96-1.0]; kappa, 0.96 [95% CI, 0.90-1.0] for DHC; and kappa, 1.0 for DMFT), indicating substantial consistency of the clinical measurements.3 The ICC for the OHIP-14 was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.95-0.99) and the kappa coefficient for the AC self-perception was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.90-1.0). Test-retest reliability values for the OHIP-14 and the AC self-perception were similar between the orthodontic and comparison groups. The internal consistency of the OHIP-14 showed a satisfactory Cronbach coefficient a of 0.73 (95% CI lower limit, 0.68). Statistically significant differences between the orthodontic and comparison groups were found for socioeconomic status, malocclusion severity, and esthetic impairment. The orthodontic group included more children at the high socioeconomic level and fewer at the low level (P 5 0.002). This group also had significantly higher DHC, AC examiner, and AC self-perception scores on the IOTN, indicating more severe American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics August 2010 malocclusions and greater normative and selfperceived treatment needs than did those in the comparison group. However, the 2 groups did not differ for age, sex, and dental health status (DMFT). These findings are shown in Table I. In this study, the OHIP-14 values had an asymmetric distribution in a favorable direction (ie, higher frequency of low OHIP-14 scores indicating relatively high OHQOL), with scores ranging from 0 to 31. In the statistical analysis, OHIP scores were transformed into a dichotomous variable by using a cutoff value of 9, the median for the whole sample35 (n 5 194). Thus, OHIP-14 scores higher than 9 were considered to reflect more negative OHQOL, and those lower than or equal to 9 indicated more favorable OHQOL. OHIP-14 scores were substantially higher in the orthodontic group, and the girls had significantly higher OHIP-14 scores than did the boys in that group (P 5 0.05). Adolescents who had sought orthodontic treatment also had higher OHQOL scores in all 7 OHIP-14 domains. In both groups, the domains that were most negatively affected were psychological discomfort (35.8%) and psychological disability (38.0%). Furthermore, severe malocclusion (DHC scores of 4 and 5), normative and self-perceived esthetic impairment (AC scores .5), and poor dental health (DMFT .5) were also statistically associated with more negative OHQOL. No statistically significant associations were found between socioeconomic status, sex, age, and OHQOL. These findings are given in Table II. Multivariate analysis was used to adjust the relationship between orthodontic treatment seeking and OHQOL.36 All potential confounding variables that showed an association (eg, malocclusion severity, decay experience, and orthodontic treatment needs) with the outcome variable (ie, more severe impact: OHIP-14 score .9) in the bivariate analyses were included in the model.4,35-38 Initially, subjects in the orthodontic group were 4.6 times more likely to report a negative impact on their quality of life than those in the comparison group. After controlling for DMFT, DHC, AC examiner, and AC self-perception, adolescents who sought orthodontic treatment still were 3.1 times more likely to report worse OHQOL than those from the comparison group, who did not seek orthodontic treatment. Severely normative and self-perceived esthetic impairment were stronger predictors of worse OHQOL than treatment seeking (Table III). Table III illustrates both unadjusted and adjusted values for DMFT, AC self-perception, AC examiner, DHC, and socioeconomic status and demonstrates their effects in negatively influencing OHQOL independently of other variables.38 Feu et al American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Volume 138, Number 2 Table I. 155 Distribution of sociodemographic characteristics, and IOTN, DMFT, and OHIP-14 scores Comparison group Socioeconomic status A or B C D Sex Male Female Age† (mean y) DMFT† IOTN-AC examiner Score 1-4 Score 5-7 Score 8-10 IOTN-AC self-perception Score 1-4 Score 5-7 Score 8-10 IOTN-DHC Score 1-3 Score 4-5 Total sample Orthodontic group Total P* n (%) n (%) n 0.002 19 66 17 (18.6) (64.7) (16.6) 49 41 2 (53.2) (44.5) (2.17) 60 115 19 (30.9) (59.3) (9.8) 0.246 60 42 13.5 1.2 (57.7) (42.3) (0.1) (0.1) 46 46 13.2 1.7 (50) (50) (0.1) (0.2) 106 88 13.6 1.4 (54.6) (45.4) (0.1) (0.1) 0.008 71 26 5 (69.6) (25.4) (4.9) 47 36 9 (51.1) (39.1) (9.78) 118 62 14 (60.8) (32.0) (7.2) 0.000 99 3 0 (97.0) (2.9) - 59 23 10 (64.1) (25.2) (10.7) 158 26 10 (81.4) (13.4) (5.2) 0.000 76 26 102 (74.5) (25.5) (52.58) 40 52 92 (43.5) (56.5) (47.42) 116 78 194 (59.8) (40.2) (100) 0.320 0.793 (%) *For ratio comparisons of proportions, the chi-square test was used and, for average means, the t test; †Line values refer to mean scores and percentages of standard deviation. DISCUSSION This cross-sectional study is one of the few in Brazil to assess the relationship between OHQOL and orthodontic treatment needs in adolescents with reliable and valid instruments: the OHIP-14 and the IOTN.4,19,24,39,40 In the future, this will allow for comparisons with similar studies conducted in other countries, helping to identify cross-cultural differences in OHQOL and esthetic perceptions. The sample was not intended to represent the entire population of 12- to 15-year-old Brazilians but, rather, to give an overview of children seeking orthodontic services at a university clinic in a large urban center of Brazil. The OHIP-14 was developed for older adults, but Ferreira et al24 found that its Brazilian version had good psychometric properties, similar to those of the original instrument, when testing the questionnaire with a group of 12-year-olds. The OHIP-14 has been successfully applied to adolescents by many authors4,23-25,27,41 because adolescents 12 years of age and above are capable of abstract thinking, reasoning about timing of past events, and correlating them with good or bad experiences.3 One might expect that a measurement instrument especially developed for children, such as the child oral health impact profile42 and the child perceptions questionnaire,43 could provide a more accurate picture of the OHQOL in this adolescent population, but, when this study was conducted, those instruments had not been translated into Brazilian Portuguese and validated. Most articles in the literature state that more females than males seek dental treatment, but the proportions of boys and girls who sought orthodontic treatment at our university clinic during the recruitment period for this study were almost the same.12,23,44,45 More girls did not obtain their parents’ consent to take part, so that the orthodontic group ended up with equal numbers of boys and girls. The situation was similar in the study of Patel et al46: because of lack of parental consent, the number of girls in the study was even lower than the number of boys. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that this might have biased our results. Children who had sought orthodontic treatment had more severe malocclusion, greater esthetic impairment (according to both their own and the examiners’ evaluations), and more negative OHQOL impacts. These results are not surprising, since these conditions are expected to predict a child’s interest in treatment. It has been shown that deviant dental appearance is a reason for teasing by peers at school and in other social situations.47 Also, children in the orthodontic group belonged to higher-income families, with expectations of self-image enhancement after orthodontic treatment tending to be higher, and this might have influenced their esthetics self-perceptions.39,47 156 Feu et al Table II. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics August 2010 Associations between sociodemographic characteristics, IOTN, DMFT, and OHIP-14 OHIP \9 (higher OHQOL) P* Socioeconomic position A or B C D Sex Male Female Group Comparison Orthodontic IOTN-AC self-perception Score 1-4 Score 5-7 Score 8-10 IOTN-AC examiner Score 1-4 Score 5-7 Score 8-10 IOTN-DHC Score 1-3 Score 4-5 DMFT† Age† (y) Total Odd ratio (95% CI) OHIP .9 (lower OHQOL) Total n (%) n (%) n (%) 0.99 1 1.05 (0.47-2.33) 1.77 (0.46-6.73) 36 81 13 (66.6) (66.9) (68.4) 18 40 6 (33.4) (33.1) (31.6) 60 115 19 (100) (100) (100) 0.22 1.65 (0.55-2.26) 75 55 (70.8) (62.5) 31 33 (29.2) (37.5) 106 88 (100) (100) 0.00 4.66 (1.35-5.70) 84 46 (82.3) (50.0) 18 46 (17.7) (50.0) 102 92 (100) (100) 0.00 1 4.0 (1.7-9.5) 26.6 (6.2-216.1) 118 11 1 (74.7) (42.3) (10.0) 40 15 9 (25.3) (57.7) (90.0) 158 29 10 (100) (100) (100) 0.00 1 2.6 (1.8-6.8) 5.11 (3.3-8.7) 91 23 7 (77.7) (37.1) (53.84) 26 39 6 (22.3) (62.9) (46.16) 117 62 13 (100) (100) (100) 0.00 3.28 (1.76-3.12) 0.05 0.08 1.24 (1.0-1.5) 0.84 (0.62-1.14) 90 40 1.2 13.7 130 (77.6) (51.3) (0.1) (0.1) (67.0) 26 38 1.7 13.4 64 (22.4) (48.7) (0.2) (0.1) (33.0) 116 78 1.4 13.6 194 (100) (100) (0.1) (0.1) (100) *For ratio comparisons, the chi-square test was used and, for averages, the t test; †Lines values refer to mean scores and percentages. Multivariate analysis showed that adolescents from the group that sought orthodontic treatment were 3.1 times more likely to have negative impacts on their quality of life, independent of their decay experience, severity of the malocclusion, and esthetic impairment. This supports other researchers’ findings in various populations—that quality of life outcomes are related not only to health and disease factors but also to subjective experiences and feelings about these factors.3,5,7,13,21,48-51 This result shows the influence of individual personality traits on OHQOL, which cannot be ignored and might, to some extent, explain why some patients are concerned about minor malocclusions and demand orthodontic intervention, whereas others accept a major deviation from the norm quite happily because it does not cause a negative impact on daily living. Corroborating these findings, Bernabé et al52 found that many adolescents with normative orthodontic treatment need experienced no impacts on OHQOL. Likewise, Oliveira and Sheiham4 found that a high percentage of Brazilian adolescents who were determined to have orthodontic treatment, and were scored with the IOTN, had no overall oral health impact. The multivariate analysis also showed that children with higher esthetic scores (ie, severely compromised esthetics), as evaluated by the examiner, were 3.9 times more likely to have negative impacts than those with no or minor esthetic treatment needs, independently of other variables. Self-perceived esthetics were even more predictive of negative OHQOL impacts; adolescents with higher AC self-perception scores were 11.7 times more likely to have negative OHQOL impacts than those with lower self-perception scores (ie, more favorable perceived esthetics). Similarly, Oliveira and Sheiham4 found that Brazilian adolescents who did not report negative OHQOL impacts were 2.5 times more likely to be satisfied with their dental appearance than those who had a negative oral impact. These results support the findings of Kok et al,53 who found a correlation between negative quality of life impacts and dental esthetic self-perceptions. Specific domains of the OHIP-14 were evaluated to determine the most important negative impacts and their correlations with other characteristics of the subjects. The domains that were most affected in both groups were psychological discomfort and psychological disability, which were also found to be related to esthetic impairment in another study.54 Prahl-Andersen55 stated that malocclusion might become enormously handicapping not because of the functional disability, but because it can adversely affect social relationships and Feu et al American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Volume 138, Number 2 Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (OR) values for predictors for OHIP-14 scores .9 Table III. Unadjusted OR (95% CI) Comparison group Orthodontic group DMFT IOTN-AC self-perception Score 1-4 Score 5-7 Score 8-10 IOTN-AC examiner Score 1-4 Score 5-7 Score 8-10 IOTN-DHC Score 1-3 Score 4-5 1 4.6 (2.4-8.9) 1.2 (1.0-1.5) 1 4.0 (1.7-9.5) 26.6 (6.2-216.1) Adjusted OR* (95% CI) 1 3.1 (1.5-6.3) 1.2 (0.9-1.5) 1 2.5 (1.0-6.5) 11.7 (1.3-100.23) 1 2.6 (1.8-6.8) 5.1 (3.3-8.7) 1 1.7 (1.2-4.1) 3.9 (2.6-7.2) 1 3.28 (1.76-3.12) 1 1.95 (0.95-3.97) 157 OHQOL when scores exceeded 5, but high scores were rare among the participants in this study. The results showed that individual personality traits probably have an influence on OHQOL, making negative impacts not always exclusively dependent on malocclusion severity. Severely compromised esthetics had the most important role in negative OHQOL, and their greatest impact was at the psychosocial level. Thus, orthodontists should be aware that both adolescent patients and their parents might expect orthodontic treatment to provide not only improved oral functioning, health, and esthetics, but also enhancement of self-esteem and social life.58 When these expectations are overblown, they might not be met, leading to dissatisfaction with the treatment outcome. The use of the OHQOL questionnaires as part of the diagnosis procedures could help orthodontists to identify and prevent these problems. *Logistic regression model adjustment test was the goodness-of-fit test of Hosmer and Lemeshow.38 P 5 0.35 showed good adjustment. CONCLUSIONS self-perceptions. The importance of these domains is consistent with other studies in Brazil that evaluated young adults who were seeking dental treatment and also found psychological discomfort to be the most negatively impacted domain.4,56 We found no sex differences in OHQOL when both the orthodontic and the comparison groups were considered. This corroborates the studies of Birkeland et al,16 Hunt et al,57 and Bernabé et al.52 Nevertheless, when the orthodontic group was evaluated alone, OHIP-14 scores were higher in the girls, in concordance with other authors’ findings.4,10,18,22,58 These results suggest that sex influences OHQOL among those who are worried about esthetics and anticipating orthodontic treatment, as Tulloch et al59 reported. Esperão60 also found that, among Brazilians who sought orthognathic surgery, OHQOL was poorer in female than in male patients. Socioeconomic status did not negatively influence quality of life outcomes in this sample; this is consistent with the findings of other researchers.10,21,41,52,60-63 Locker21 and Shaw et al63 concluded that the negative influence on OHQOL in subjects with lower socioeconomic status was because of poorer general oral health, such as greater decay and periodontal disease. In our study, the comparison group included 81.3% of subjects with lower socioeconomic statuses (classes C-E), compared with 46.7% in the orthodontic group. Nevertheless, their OHQOL scores were generally more favorable than those of the children in the orthodontic group. Children in the comparison group received regular dental care during their school years, as evidenced by their low DMFT scores, slightly lower than those of the orthodontic group. DMFT had a negative influence on In this cross-sectional study of Brazilian adolescents (aged 12-15 years), those who had sought orthodontic treatment had a higher chance of reporting worse OHQOL than did those who had never sought treatment, independently of dental caries status, malocclusion severity, and esthetic impairment, whether selfperceived or evaluated by an orthodontist. Nevertheless, severely compromised esthetics was a better predictor of worse OHQOL than orthodontic treatment seeking. REFERENCES 1. Dolan TA, Gooch BF. Dental health questions from the Rand Health Insurance study. In: Slade GD, editor. Measuring oral health and quality of life. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina; 1997. p. 8-31. 2. Fernandes MJ, Ruta DA, Ogden GR, Pitts NB, Ogston SA. Assessing oral health-related quality of life in general dental practice in Scotland: validation of the OHIP-14. Community Dent Health 2006;34:53-62. 3. Hetherington EM, Parke RD, Locke VO. Child psychology: a contemporary viewpoint. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. 4. Oliveira CM, Sheiham A. Orthodontic treatment and its impact on oral health-related quality of life in Brazilian adolescents. J Orthod 2004;31:20-7. 5. Shaw WC, Addy M, Ray C. Dental and social effects of malocclusion and effectiveness of orthodontic treatment: a review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1980;8:36-45. 6. Locker D. Oral health and quality of life. Oral Health Prev Dent 2004;2:247-53. 7. Abeles R, Gift H, Ory M. Aging and quality of life. 1st ed. New York: Springer; 1994. 8. Albino JE, Cunat JJ, Fox RN, Tedesco LA. Variables discriminating individuals who seek orthodontic treatment. J Dent Res 1981; 60:1661-7. 9. Gherunpong S, Tsakos G, Sheiham A. The prevalence and severity of oral impacts on daily performances in Thai primary school children. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;12:57-60. 158 Feu et al 10. Shaw WC. Factors influencing the desire for orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod 1981;3:151-62. 11. Zhang M, McGrath C, Hägg U. The impact of malocclusion and its treatment on quality of life: a literature review. Int J Paediatr Dent 2006;16:381-7. 12. Kiyak HA. Cultural and psychological influences on treatment demand. Semin Orthod 2000;26:504-14. 13. Locker D. Concepts of oral health, disease and the quality of life. In: Slade GD, editor. Measuring oral health and quality of life. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina; 1997. p. 45-58. 14. Mandall NA, Wright J, Conboy F, Kay E, Harvey L, O’Brien KD. Index of orthodontic treatment need as a predictor of orthodontic treatment uptake. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005;128: 703-7. 15. McComb JL, Wright JL, Fox NA. Perceptions of the risks and benefits of orthodontic treatment. Community Dent Health 1996;13:133-8. 16. Birkeland K, Boe OE, Wisth P. Subjective evaluation of dental and psychological results after orthodontic treatment. J Orofac Orthop 1997;58:44-61. 17. Klages U, Bruckner A, Zentner A. Dental aesthetics, selfawareness, and oral health-related quality of life. Eur J Orthod 2002;24:53-9. 18. Gravely JF. A study of need and demand for orthodontic treatment in two contrasting National Health Service Regions. Br J Orthod 1990;17:287-92. 19. Oliveira BH, Nadanovsky P. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the oral health impact profile-short form. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005;33:307-14. 20. Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the oral health impact profile. Community Dent Health 1994;11:3-11. 21. Locker D. Measuring oral health: a conceptual framework. Community Dent Health 1988;5:3-18. 22. Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997;25:284-90. 23. Broder HL, Slade GD, Caine R, Reisine S. Perceived impact of oral health conditions among minority adolescents. J Public Health Dent 2000;60:189-92. 24. Ferreira CA, Loureiro CA, Araujo VE. Psycometrics properties of subjetive indicator in children. Rev Saude Publica 2004;38:445-52. 25. Goes PSA. The prevalence and impact of dental pain in Brazilian schoolchildren and their families [thesis]. London, United Kingdom: London University; 2001. 26. Soe KK, Gelbier S, Robinson PG. Reliability and validity of two oral health related quality of life measures in Myanmar adolescents. Community Dent Health 2004;21:306-11. 27. Lopez R, Baelum V. Oral health impact of periodontal diseases in adolescents. J Dent Res 2007;86:1105-9. 28. Almeida AM, Loureiro CA, Araújo VE. Um estudo transcultural de valores de saúde bucal utilizando o instrumento OHIP-14 (oral health impact profile) na forma simplificada. Parte I: adaptação cultural e lingü!ıstica. UFES Rev Odontol 2004;6:6-15. 29. Associação Brasileira de Anunciantes. Classificação Econômica Brasil. São Paulo, Brazil: Associação Brasileira de Anunciantes; 1996. 30. Brook PH, Shaw WC. The development of an index of orthodontic treatment priority. Eur J Orthod 1989;11:309-20. 31. World Health Organization. Oral heath surveys—basic methods. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. 32. Birkeland K, Boe OE, Wisth P. Orthodontic concern among 11-year-old children and their parents compared with orthodontic treatment need assessed by the index of orthodontic treatment need. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996;110:197-205. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics August 2010 33. Mandall NA, McCord JF, Blinkhorn AS, Worthington HV, O’Brien KD. Perceived esthetic impact of malocclusion and oral self-perceptions in 14-15-year-old Asian and Caucasian children in greater Manchester. Eur J Orthod 2000;22:175-83. 34. Stenvik A, Espeland L, Linge BO, Linge L. Lay attitudes to dental appearance and need for orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod 1997;19:271-7. 35. John MT, Koepsell TD, Hujoel P, Miglioretti DL, LeResche L, Michedlis W. Demographic factors, denture status and oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004;32:125-32. 36. Landis R, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159-74. 37. Chavers LS, Gilbert GH, Shelton BJ. Two-year incidence of oral disadvantage, a measure of oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003;31:21-9. 38. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 1st ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. 39. Eagly AH, Ashmore RD, Makhijani MG, Longo LC. What is beautiful is good, but.: a meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychol Bull 1991;110: 109-28. 40. Marques LS, Ramos-Jorge ML, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA. Malocclusion: esthetic impact and quality of life among Brazilian schoolchildren. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129: 424-7. 41. Thomas CW, Primosch RE. Changes in incremental weight and well-being of children with rampant caries following complete dental rehabilitation. Pediatr Dent 2002;24:109-13. 42. Broder HL, McGrath C, Cisneros GL. Questionnaire development: face validity and item impact testing of child oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007;1:8-19. 43. Jokovic A, Locker D, Stephens M, Kenny D, Tompson B, Guyatt G. Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for measuring child oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res 2002;81: 459-63. 44. Al Yami EA, Kuijpers-Jagman AM, Van’t Hof MA. Orthodontic treatment need prior to orthodontic treatment and 5 years postretention. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1998;26:421-7. 45. Locker D, Jokovic A, Clarke M. Assessing the responsiveness of measures of oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004;32:10-8. 46. Patel RR, Tootla R, Inglehart MR. Does oral health affect self perceptions, parental ratings and video-based assessments of children’s smiles. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007;35: 44-52. 47. Klages U, Zentner A. Dentofacial aesthetics and quality of life. Semin Orthod 2007;13:104-15. 48. Allison P, Locker D, Feine J. Quality of life: a dynamic construct. Soc Sci Med 1998;24:224-35. 49. Locker D, Slade GD. Oral health and quality of life among older adults: the oral health impact profile. J Can Dent Assoc 1994;59: 830-3. 50. Sheiham A. The role of the dental team in promoting dental health and general health through oral health. Int Dent J 1992;42:223-8. 51. Sheiham A, Spencer J. Health needs assessment. Oxford, United Kingdom: Wright; 1997. 52. Bernabé E, Tsakos G, Oliveira CM, Sheiham A. Impacts on daily performances attributed to malocclusions using the conditionspecific feature of the oral impacts on daily performances index. Angle Orthod 2008;78:241-7. 53. Kok YV, Mageson P, Harradine NW, Sprod AJ. Comparing a quality of life measure and the aesthetic component of the index of American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Volume 138, Number 2 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. orthodontic treatment need (IOTN) in assessing orthodontic treatment need and concern. J Orthod 2004;31:312-8. Wong AHH, Cheung CS, McGrath C. Developing a short form of oral health impact profile (OHIP) for dental aesthetics: OHIPaesthetic. Community Dent Health 2007;35:64-72. Prahl-Andersen B. The need for orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod 1978;48:1-9. Gonçalves JR, Almeida AM. Avaliação do impacto percebido da saúde bucal utilizando o instrumento OHIP-14. Rev Odontol UFES 2004;6:11-6. Hunt O, Hepper P, Johnston C, Stevenson M, Burden D. The aesthetic component of the index of orthodontic treatment need validated against lay opinion. Eur J Orthod 2002;24:53-9. Tung AW, Kiyak HA. Psychological influences on the timing of orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998; 113:29-39. Feu et al 159 59. Tulloch JFC. Shaw wC, Underhill C, Smith A, Jones G, Jones M. A comparison of attitudes toward orthodontic treatment in British and American communities. Am J Orthod 1984;85: 253-9. 60. Esperão PT. Qualidade de vida associada à saúde bucal em pacientes orto-cirúrgicos [thesis]. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Rio de Janeiro State University; 2006. 61. Atchison KA, Dolan TA. Development of the geriatric oral health assessment index. J Dent Educ 1990;54:680-7. 62. Inglehart M, Bagramian RA. Oral health-related quality of life—introduction and overview. In: Oral Health-Related Quality of Life, M. Rohr Inglehart and R. A. Bagramian, editors. Oral healthrelated quality of life. 1st ed. Chicago: Quintessence; 2002. p. 1-6. 63. Shaw WC, Richmond S, O’Brien KD, Brook P, Stephens CD. Quality control in orthodontics: indices of treatment need and treatment standards. Br Dent J 1991;170:107-12.