* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

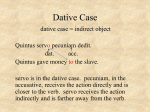

Download PERSONAL AND REFLEXIVE PRONOUNS 1. Introduction

Ukrainian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Udmurt grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ojibwe grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sotho parts of speech wikipedia , lookup

Latvian declension wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Literary Welsh morphology wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Italian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Norse morphology wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Romanian nouns wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup