* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download outline26497

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

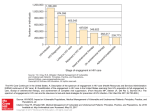

I. Introduction a. What has changed: newest guidelines for treatment (2009 DHHS) now advocate treatment sooner than later. b. What has changed: life expectancies have lengthened significantly (the present expectation is a shortening of the typical life expectancy by 10-15 years). c. What has changed: newer medications and new drug classes i. Fusion inhibitor – enfuvirtide/Fuzeon ii. New protease inhibitors with different resistance profiles – tipranavir/Aptivus, darunavir/Prezista iii. Chemokine binding inhibitor – maraviroc/Selzentry iv. Integrase inhibitor – raltegravir/Isentress d. What has changed: CMV retinitis behaves differently; it is controlled by restored immunity in successful antiretroviral therapy, and even with partially successful antiretroviral therapy, it is less rapidly progressive d. What has not changed: a significant number of patients are unaware of their infection. e. What has not changed: a large number of patients diagnosed as HIVpositive either have AIDS at the time of initial diagnosis or progress to AIDS within 1 year of initial diagnosis. f. What has not changed: left untreated, HIV infection is a lethal disease and there remains no cure. II. Treatment guidelines a. Guidelines for treatment have varied over the years. Initially (with the appearance of zidovudine), every patient was treated (even with high CD4 counts). With the advent of protease inhibitors (1996 and later), the philosophy was “hit early, hit hard,” echoing what was mandatory in the treatment of an infectious disease. Then toxicities from protease inhibitors (diabetes, increased cardiovascular risk, lipodystrophy) manifested, driving early treatment back to a “wait until 200” stance. Further research (NA-ACCORD study has noted better survival with a return to earlier therapy. b. Current standards urge treatment for the following: i. Anyone with an AIDS-defining illness ii. Anyone HIV seropositive woman who is pregnant, any seropositive individual with HIV nephropathy, any seropositive individual with hepatitis B infection (possibly hepatitis C also) iii. Any HIV seropositive patients with CD4 cell counts 350 or lower. iv. Serious consideration of treatment of all HIV seropositive patients with CD4 counts between 350 and 500. The DHHS committee’s latest guidelines, from November 2009, are split 55-45 for this stance: strong recommendation vs. moderate recommendation. v. Seriously consider treatment of all HIV seropositive patients with CD4 counts over 500 (the DHHS committee split 50-50 for treatment initiation vs. optional). c. Why the shift to earlier treatment? i. Medications are simpler to adhere to: once-daily, more manageable toxicities, and coformulations which reduce the pill volume. ii. Better survival is associated with new when-to-treat starting points; the NA-ACCORD trial, and the subset trial of START both indicate better survival. There is the suggestion that earlier control of HIV and reduction of inflammation generally contribute to better survival. iii. Pushing against earlier treatment remain the specters of unknown, long-distant toxicities with long-duration therapy, and likelier treatment fatigue and non-adherence, with the risk of development of resistant virus. d. Treatment guidelines (DHHS 2009): i. Consistently use a 2-drug ‘backbone’ plus a third drug for untreated patients; either nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NtRTI). 1. Tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada coformulation) 2. Tenofovir + lamivudine 3. Zidovudine/lamivudine (Combivir coformulation) 4. Zidovudine + emtricitabine 5. Abacavir + lamivudine (Epzicom coformulation) ii. The choice of critical third drug has changed; it continues to be either a protease inhibitor (PI) or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) for untreated patients. 1. Efavirenz/Sustiva still is the NNRTI of choice – once daily, and most conveniently coformulated as Atripla (efavirenz, tenofovir, and emtricitabine). 2. Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir) is no longer the first choice PI; it has dropped off the top tier due to some increased slack in viral control at 2+ years (consistent with the twice-daily dosing plus ritonavir boost of 200 mg per dose, which has definite GI toxicity). 3. Atazanavir/Reyataz (with boosting ritonavir, once daily) and darunavir/Prezista (with boosting ritonavir, once daily) are now first choice PIs; tolerance is better, once-daily treatment is possible, and the boosting level of ritonavir is lower than with Kaletra. 4. Raltegravir/Isentress has been added to the top tier of preferred drugs; although a twice daily drug, it has neither the CNS toxicity of efavirenz or GI upset with ritonavir. iii. Other drugs from the dark ages are rarely used now 1. NNRTI: delavirdine 2. PI: indinavir, nelfinavir, amprenavir, full-dose ritonavir, saquinavir 3. NRTI: ddc (d-c’d 2006), didanosine, stavudine; the latter two are still used but are difficult for either food/diet requirements or for toxicity issues. III. Medications: established classes which have expanded, and new/unique classes to which treatment-experienced patients are unexposed. a. There are more than 20 approved antiretroviral drugs in 7 mechanistic classes for treatment of HIV infection. b. NRTI (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors): drugs date from 1987 (introduction of zidovudine/Retrovir) to 2003 (emtricitabine/Emtriva) c. Nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor: tenofovir/Viread (2001) d. Protease inhibitors: dating from 1995 (saquinavir/Invirase) to 2006 (darunavir/Prezista) e. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors: dating from 1995 (nevirapine/Viramune) to 2008 (etravirine/Intelence) f. Fusion inhibitor (enfuvirtide/Fuzeon), from 2003 g. Chemokine binding inhibitor (CCR5 inhibitor) maraviroc/Selzentry, 2007 h. Integrase inhibitor (raltegravir/Isentress), 2009 i. New drugs (particularly those introduced since 2005) are better able to withstand virus resistant to other members within the drug class (tipranavir/Aptivus for experienced patients, and darunavir/Prezista, both with ability to manage PI-resistant virus, etravirine/Intelence with ability to manage NNRTI-resistant virus). New classes of drugs (CCR5 binding inhibitor, integrase inhibitor) to which patients should be fully susceptible (since previously unexposed) allow long-term survivors (with multi-drug resistant virus) who have burned through all the older/standard drug choices the opportunity to experience some survival benefit. There are both better drugs to start with as well as better drugs that can be used later. j. As important as the new drug groups have been changes in coformulations (Combivir, Epzicom, Trizivir, Kaletra,Truvada, Atripla), once-daily medication dosing (from either efavirenz, or ritonavir-boosted PIs used once-daily), and better tolerability (newer PIs use lower boosting doses of ritonavir, which makes a big difference). IV. Ocular manifestations seen with HIV-AIDS a. CMV retinitis is uncommon at this time. Individuals with successful cART therapy are able to stop anti-CMV retinitis drugs indefinitely with the restoration of CMV-specific immunity as they have regained some degree of immunocompetence. Even individuals with suboptimal response to cART have CMV retinitis that is less rapidly progressive. b. Recalling that a significant number of individuals are initially diagnosed with HIV seropositivity with clinical AIDS (CD4 lower than 200), there remains the potential for observation of ocular opportunistic infections reminiscent of the bad old days. i. HIV retinitis: cotton wool spots, relating possibly to higher viral load than to CD4 counts (??) ii. Intraocular manifestations of systemic diseases: tuberculosis, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, cryptococcosis c. Ocular opportunistic infections related to systemic infection may occur, some depending on the CD4 nadir associated with the disease i. CMV – typically with CD4 very low (usually < 50) ii. Syphilis – quite variable iii. Tuberculosis – quite variable iv. Toxoplasmosis and cryptococcosis – typically with CD4 < 100 V. What has changed over the past 30 years? a. HIV is able to be frequently managed as a chronic condition. Patients can continue to enjoy the benefits initially experienced with the advent of protease inhibitors in 1996, as frequently inexorable wasting and declining patients obtained a new lease on life. b. HIV-infected individuals ultimately succumb less to opportunistic infections than to conditions rarely seen in the first 15 years of the epidemic: kidney disease, liver disease, cardiovascular disease, cancers not specific to HIV. Instead of a ‘death sentence’ that was common in the 80’s, when a diagnosis of AIDS left the patient with two years or less of life, now patients can actually expect a foreshortened but almost normal life expectancy. “Old” and “HIV” can be used to describe the same person and are no longer an oxymoron. c. Testing procedures have changed dramatically. Oral testing is as dependable as the blood ELISA test, and results are available that day. Opt-out testing philosophies have changed the way in which HIV testing is administered, so that HIV testing is considered to be a (somewhat) routine blood test. d. Genotypic resistance testing is mandatory prior to starting therapy in any patient, as a means of structuring the regimen for optimal success. e. Survival is vastly different. HIV is no longer a death sentence. But the deadly seriousness of the epidemic is watered down; 20- and 30somethings have absolutely no knowledge of the immensity of the epidemic in the decade of the 80’s and 90’s, when one’s peer group was effectively being decimated, with individuals experiencing loss of productivity, increasing disability, inexorable decline, and a grim fate. Given the lack of historical perspective, HIV is unfortunately relegated to a back burner, with a lack of urgency for advocacy and the still-critical prevention messages not having the immediacy they once had. Remember safe sex? f. Is the cup half full or half empty? Given the expansion of drugs, the cup is more than half-full for long-term survivors desperately needing a unique drug class for successful treatment. Given the greater tolerability and ease of administration of medications, individuals have greater success with initial treatment and longer durability as well. Given all of this, the transition has been made from an almost universally fatal disease to a chronic one – this is indeed good news, but is tempered by the undeniable fact that the epidemic is not over. VI. References a. Starting therapy and benefits of therapy i. Sterne JA et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet 2009; 373:1352-63. ii. Emery S et al. Major clinical outcomes in antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naïve participants and in those not receiving ART at baseline in the SMART study. J Infect Dis 2008; 197:1133-44. iii. Kitahata MM et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:1815-26. iv. El-Sadr WM et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2283-96. v. Hazenberg MD et al. Persistent immune activation in HIV-1 infection is associated with progression to AIDS. AIDS 2003; 17:1881-8. vi. Willig JH et al. Increased regimen durability in the era of oncedaily fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2008; 22:1951-60. b. Testing i. Grigoryan A et al. Late HIV diagnosis and determinants of progression to AIDS or death after HIV diagnosis among injection drug users, 33 US States, 1996-2004. PLoS One 2009; 4(2):E4445. ii. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Late HIV testing – 34 states, 1996-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58(24):661-5. iii. Branson BM et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55(RR-14):1-17. iv. Granich RM et al. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet 2009; 373:48-5 c. Anti-HIV drugs i. Markowitz M et al. Sustained antiretroviral effect of raltegravir after 96 weeks of combination therapy in treatment-naïve patients with HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 52:350-6. ii. Riddler SA et al. Class-sparing regimens for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2095-2106. iii. Malan DR et al. Efficacy and safety of atazanavir, with or without ritonaivr, as part of once-daily highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens in antiretroviral-naïve patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47:161-7. iv. Mills AM et al. Once-daily darunavir/ritonavir vs. lopinavir/ritonavir in treatment-naïve, HIV-1-infected patients: 96-week analysis. AIDS 2009; 23:1679-88. v. Staszewski S et al. Efavirenz plus zidovudine and lamivudine, efavirenz plus indinavir, and indinavir plus zidovudine and lamivudine in the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults. Study 006 Team. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:1865-73. vi. Yost R et al. Maraviroc: a coreceptor CCR5 antagonist for management of HIV infection. Am J Health-System Pharm 2009; 66:715-26. vii. Hicks CB et al. Durable efficacy of tipranavir-ritonavir in combination with an optimized background regimen of antiretroviral drugs for treatment-experienced HIV-1-infected patients at 48 weeks in the Randomized Evaluation of Strategic Intervention in multi-drug reSistant patients with Tipranavir (RESIST) studies: an analysis of combined data from two randomized open-label trials. Lancet 2006; 368:466-75. d. Eye-related issues and cytomegalovirus retinitis i. Holland GN et al. Characteristics of untreated AIDS-related cytomegalovirus retinitis. I. Findings before the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (1988 to 1994). Am J Ophthalmol 2008; 145:5-11. ii. Holland GN et al. Characteristics of untreated AIDS-related cytomegalovirus retinitis. II. Findings in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (1997 to 2000). Am J Ophthalmology 2008; 145:12-22. iii. Holland GN. AIDS and ophthalmology: the first quarter century. Am J Ophthalmol 2008; 145:397-408. Major guidelines: Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services. December 1, 2009; 1-161. Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed 2-1-10. Kaplan JE et al. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep 2009; 58(RR-4):1-207.