* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Party Nationalization and Institutions

Political parties in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Ethnocultural politics in the United States wikipedia , lookup

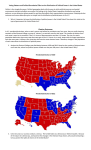

Elections in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Swing state wikipedia , lookup

Third Party System wikipedia , lookup

Electoral reform in the United States wikipedia , lookup

American election campaigns in the 19th century wikipedia , lookup