* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

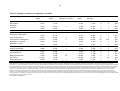

Download Determinants of Microinsurance Demand: Evidence from a Micro

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript