* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Solutions to Problem Set 5

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

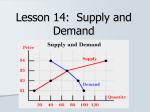

Prof. Richard Tresch EC 131 Rucha Bhate Solutions to Problem Set 5 Q. 7. Chapter 7, P 161. a) Marginal cost is the cost of producing one additional unit of output by the firm. For a competitive firm, the marginal cost curve is nothing but its supply curve. A typical profit maximizing firm will continue production till the point where Price P = MC (Best profit supply rule). Assuming all the firms in the market are identical, we can argue that if one firms follows the P = MC rule, everyone will do so. This means, the marginal cost curve is directly related to the market supply curve, which is the horizontal summation of individual firm’s supply curves. Marginal value is the value that a consumer derives from consuming one extra unit of a particular good. A typical consumer seeks to maximize the value (utility) that he derives from consuming goods and services. Hence he would be willing to buy and consume a product as long as the price he has to pay (P) is less than equal to his marginal value and he will keep demanding it until P = Marginal Value. Assuming all the consumers behave in this manner, we can argue that marginal value is linked with market demand curve, which is the horizontal summation of the individual demand curves. Graphically, marginal cost can be depicted by the vertical distance to the supply curve at a particular quantity and marginal value is the vertical distance to the demand curve at a specific quantity. As discussed before, both marginal cost and marginal value are intimately linked with the notion of market price. Price is a common factor that links both sides of the market namely; the buyers (consumers) and sellers (firms). It contains all the relevant economic information useful to either party that enters a market to exchange goods. b) In the numerical example given on page 161; quantity 28 appears both in the demand as well as the supply column. Now, marginal cost associated with Q = 28 equals 20, which is entry corresponding to QS = 28 (quantity supplied) under the price column. Similarly, marginal value associated with Q = 28 equals 8, which is the value under the price column associated with QD =28 (quantity demanded). Q 8. Chap 7, P.161 We can draw the standard demand –supply cross diagram to graphically show and explain some important concepts. Price S B P* E D A Quantity 0 Q* In the above figure, we have the downward sloping demand curve and the upward sloping supply curve which intersect at point E thus giving us equilibrium quantity = Q* and equilibrium price = P*. Total cost TC is given by the area OAEQ*. Given that marginal cost for an extra unit of quantity is the vertical distance to the supply curve, we can sum the marginal costs going from 0 to Q* thus reflecting total cost of producing Q* worth of output. Thus, total cost is the area under the supply curve bounded by the origin (O) and the equilibrium quantity. Total value TV is given by the area OBEQ*. Given that marginal value is the vertical distance to the demand curve, we can add the marginal values associated with successive units of Q to yield a measure of total value. Therefore, total value is the area under the demand curve bounded by the origin and the equilibrium quantity. The society’s economic problem is to maximize net value NV. Net value is the difference between total value and total cost. Thus, NV = TV – TC. We are netting out the cost of producing a specific quantity (here Q*) from the total value generated by the same. In the graph, NV is shown by the triangle ABE. Net value can be interpreted as the total surplus that is left with the society after the market activity is completed. It is the pie that in turn gets distributed between the firms and the consumers, who are the two claimant of the surplus. Consumer surplus CS is the area P*BE. It is a part of the net value that is enjoyed by the consumers. It is derived from the fact that between quantity O and Q*, the consumers marginal value (and hence willingness to pay) is higher than the equilibrium market price that he actually ends up paying. This benefit is cumulated for all the quantities till Q* to yield the relevant triangle of consumer surplus. Thus, CS is the area under the demand curve and above the equilibrium price level bounded by O and Q*. Producers surplus PS is the area P*BA. It is the portion of net value that constitutes the benefit to the firms. It is derived from the fact that between O and Q*, the marginal cost of producing an extra unit of output is lower than the equilibrium price that the firm can charge in the market. Thus, firm is enjoying profit till point Q* given by the relevant triangle P*BA. Notice that consumer surplus and producer surplus together exhaust the net value (CS + PS = NV). Q.9. Chap. 7, P.161. Here we need to envision a situation wherein the entire pie (net value) is appropriated either by consumer or producers leaving nothing for the other party. Thus the net value is not divided between the two parties in a market transaction as argued before, but is solely enjoyed by either one of them. We can imagine a case wherein the demand curve is horizontal (perfectly elastic) and supply curve is upward sloping. In this case, the usual analysis shows that the producers will garner all the net value as producer surplus (PS = NV) and Consumer surplus will be zero. Similarly, when the supply curve is horizontal and demand curve downward sloping, the consumers will get the entire net value as consumer surplus (CS = NV) and the firms won’t enjoy any surplus. In either of these cases, one party takes advantage of the fact that the other party’s demand/ supply response is extremely sensitive and hence manipulates the price in such a way that it takes away the entire net value resulting from the market equilibrium. Even though, we can think and construct such situations graphically, they are not completely realistic. Notice that horizontal demand curves can exist in a perfectly competitive market, but perfect competition is not something we observed in reality. Firms are not always price takers in real world and often exert some monopoly power. Thus, these cases are valid only under extremely restrictive market scenarios and very strict conditions which might not be observed in reality. II. Market for Widgets We are given a market for widgets wherein the demand curve is upward sloping and supply curve is downward sloping. Considering both the curves display exactly the opposite behavior from their competitive market counterparts, this market obviously does not represent the standard competitive market that we have studied so far. In fact, all that we have learned about the demand, supply and their interaction in market equilibrium is turned upside down in this artificially created setting We can make use of this example to compare it with the standard case and learn what is different about this new market as compared to our usual demand-supple diagram. Knowing what is wrong with this graph would help us identify what is right about the original demand-supply framework. 1. The market for widgets violates both the law of demand and law of supply. Law of demand states that other things being equal, higher the price the lower the quantity demanded. Moreover, as price of a good rises, the consumers favor its cheaper substitutes (substitution effect) thus reducing demand for the good in question. Also as price rises, the purchasing power/real income falls thus lowering the quantity demanded (income effect). In the market for widgets we see, the higher the price, larger the quantity demanded, which is contrary to the standard law of demand. Similarly with supply curve. The supply curve in market for widgets is downward sloping meaning higher the price, lower the quantity supplied. This is contrary to the law of supply implying an upward sloping supply curve. 2. The equilibrium associated with market for widgets is not stable. Notice what happens when the price rises above the equilibrium price P*. We are in a situation of excess demand as demand is greater than supply. Thus, consumers would bid the price up. So there is way that we can travel back to the original equilibrium. In fact, as the price rises above P* it would keep rising forever thus resulting in an exploding/unstable equilibrium. We can analyses the case with excess supply similarly. Therefore, market forces do not bring us back to the equilibrium in market for widgets. Thus, it is not a place or rest or a stable equilibrium. 3. In our standard demand-supply diagram, we can analyze the shifts (increase or decrease) in demand or supply and exactly predict what will happen to price and quantity. For example, as demand rises (shifts up to the right) and supply remains constant, the equilibrium quantity rises and the price rises as well (due to excess demand situation). However, with market for widgets such analysis is ambiguous. As demand rises, we see that the quantity is rising but the price is falling (if you shift the demand curve to the right) and the reverse picture if the shift is in the other direction. This defies our intuition. Therefore we cannot accurately see what is happening to both price and quantity. If we are correct in predicting the price response, the quantity prediction is off and vice versa. 4. Lastly, in the market for widgets we can observe that the net value is negative as the total cost is much higher than the total value generated (TC and TV areas area reversed here). Thus the society is minimizing the net value in this case. Net value becomes positive beyond equilibrium quantity Q*, but this means we are no longer operating under competitive equilibrium.