* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 投影片 1

Economic planning wikipedia , lookup

Participatory economics wikipedia , lookup

Economic democracy wikipedia , lookup

Production for use wikipedia , lookup

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

Economics of fascism wikipedia , lookup

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Post–World War II economic expansion wikipedia , lookup

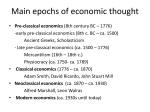

Perspectives on capitalism by school of thought wikipedia , lookup

社會科學概論 高永光老師 上課使用 Classroom Only Physiocracy: The First Economic Model The branch of social science called ‘economies’ is commonly described as the study of how humans make use of available productive resources (including their own labour and skills) to produce goods and services for human use. This is partly a technical question of the relationship between “inputs” and “outputs” but it becomes a matter of social science, rather than physics or engineering, because humans practise a high degree of functional specialization. This raises the questions of how the specialized economic activities of individuals are co-ordinated into an orderly system; how different systems of co-ordination work; and what defects or deficiencies a particular system has and how they may be corrected. The study of such questions is as ancient as any of mans intellectual interests but effective systematic investigation of them is quite recent. Most historians of economics would date it no earlier than the latter half of the eighteenth century. Adam Smith is sometimes described as the father of economics, but shortly before his great Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) was published in England, there flourished in France, at the court of Louis XV, a group of writers to whom must be given the credit for attempting to construct the first systematic and comprehensive theoretical model of economic processes. These were the “Physiocrats”. A. EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE AND THE PHYSIOCRATIC SCHOOL The long reign of Louis XIV, which ended in 1715, left France with a magnificent court and a nearly ruined economy. Louis engaged in a series of I wars and built the lavish palace of Versailles, activities that cost much and produced little. In addition he expelled the Protestants from France, which thus lost some of its most skilled and talented human resources. He proclaimed himself absolute and tolerated no criticism, thus stifling another source of productivity. His Finance Minister, Colbert, embarked on a policy of encouraging industry which emphasized economic activities for which France was not particularly suited and hampered agriculture, in which the country had rich natural resources. The result of this reign of folly was that the economy of France was overburdened by regulations and twisted by policies that stunted its productivity, and, despite the crushing burden of taxes, the flow of revenues into the national exchequer was insufficient to match expenditures. The state sank ever more deeply into debt. The originator of the Physiocratic doctrine, Francois Quesnay (1694-1774), was brought up in peasant surroundings, despite the fact that his father was a lawyer. He head little formal education and was taught to read by a friendly gardener at the age of twelve. B. THE PHYSIOCRATIC MODEL The term ‘Physiocracy’ suggests to the English ear something like ‘physiology’ which is an especially tempting interpretation when one knows that Quesnay was a physician. But in fact the term connotes in French the more general concept of law of nature. The Physiocratic model was built on the idea that social phenomena are governed, as are physical phenomena, by laws of nature that are independent of human will and intention. The basic idea underlying the Physiocratic model is that goods and services are produced not for the direct use of their producers but for sale to others. The economy is viewed from the standpoint of markets, as a system of money transactions. C. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF PHYSIOCRACY IN THE HISTORY OF SOCIAL CIENCE 1.The concept of spontaneous order The most important idea of the Physiocrats was that economic processes are governed by laws of nature in such a way that the economic world, like the natural world, is, or can be, a system of spontaneous order: not man-made or mangoverned. This ran counter to much of the economic thinking of the eighteenth century, which viewed the economy as something that required constant management and extensive regulation by the state. As noted above, the Physiocrats did not argue that the institution of the state could be dispensed with; in fact, they favoured despotic government, but they contended that its economic role could be greatly reduced because of the existence of a mechanism of spontaneous order operating through market processes. 2. Economic classes The idea that human society is a hierarchical structure and that this structure is composed of distinct and discrete social classes so old that it can hardly be traced. But the Physiocratic model involved an important innovation in how the class structure of society is conceived by the social scientists. Instead of using the traditional status categories (such as the ‘nobles’, ‘clergy’, and ‘third estate’ of French Politics) the Tableau contains categories or classes that are economic in nature. This is undoubtedly one of the main reasons why Karl Marx admired the Physiocrats: he felt that recognition of the economic basis of class structure was absolutely necessary to the development of social science. 3. Circular flow The modelling of the economy as a circular flow of expenditure is familiar today to any student who has taken an introductory college course in economics. This cannot, however, be traced directly to the Physiocrats. The classical economists did not pick up the Physiocratic concept of circular flow as an analytic tool. Karl Marx used it to some extent in his theory of capitalist economic development but he did not build his own basic economic model around it. Its revival as an analytical paradigm was mainly due to the work of John Maynard Keynes, whose General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936) has been the most influential book in economics of the twentieth century responsible for establishing macroeconomics as a major branch of modern economic theory, and for changing the views of economists, and others, on the economic role of the state. 4. Surplus The idea of a 'net product' or surplus plays a large role in Physiocratic theory. Indeed, the main object of the Tableau was to contend that there is such a surplus and to locate its origin in land. The concept of surplus occupies an important place in the history of economic theory, playing a central role (after the Physiocrats) in classical economics, Marx's economics, and the model of efficient resource use developed by the neoclassical school in the late nineteenth century. This aspect of economics is the main point of contact between scientific analysis and ethical judgements in economics, as we shall see later in this book when we examine Ricardo's theory of rent, Marx's theory of exploitation, and Alfred Marshall's theory of maximum welfare. 5. The single tax As we shall see later, the idea of land rent as the proper object of taxation and the concept of a single tax reappeared more than a century after the Physiocrats in a book by Henry George called Progress and Poverty (1879). This became a popular best seller in both America and England and was important in developing the line of reformist political thought represented by non-Marxist, democratic socialist movement. Henry George himself was not a socialist; he felt that he had discovered the one great defect of a capitalist system, which could be corrected by a single tax on land values or rent. In Progess and Poverty the foundation of George’s argument was Ricardo’s theory of rent, but he dedicated his later Protection or Free Trade (1891) to the Physiocrats 6. Advances In classical economics three categories of factors of production are employed for analytical purposes: land, labour, and capital. The third of these has posed problems of special difficulty for economic theory, many of which are associated with the fact that capitalusing methods of production involve time. If, say, instead of gathering fruit as best one can with one's bare hands, labour is first devoted to making a fruit-picking tool, the total production of fruit may be increased, but its availability is postponed. There are many economic activities that have this essential nature: increasing, but delaying, production. 7. Ideology The Physiocrats, as noted above, were a group of disciples gathered around a master, convinced that they possessed the truth on essential issues of economics. Most of them would have acknowledged that there were still some unsolved scientific problems, but these were regarded as minor; the main task was to convey the truth to others, especially those with political power. Put this way, Physiocracy resembles the ideology of a sect more than the views of a community of scientists. The line between what is a scientific theory and what is a sectarian ideology is difficult to draw, and frequently depends much on who is doing the drawing; one man’s ‘science’ may be another's ‘ideology’. Sectarianism and an ideological attitude towards knowledge is not completely absent in natural science but a notable feature of that area of human knowledge is its development, in modem times, of objective criteria by which the validity of empirical propositions may be tested.