* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 1 1942-1961 March 1942 “Notes and Documents

Fort Fisher wikipedia , lookup

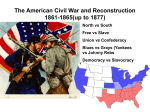

Cavalry in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Capture of New Orleans wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Perryville wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Anaconda Plan wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Wilson's Creek wikipedia , lookup

Arkansas in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Donelson wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Seven Pines wikipedia , lookup

Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps wikipedia , lookup

Economy of the Confederate States of America wikipedia , lookup

Issues of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of New Bern wikipedia , lookup

First Battle of Bull Run wikipedia , lookup

Second Battle of Corinth wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Shiloh wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Namozine Church wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Stones River wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Galvanized Yankees wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Island Number Ten wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Henry wikipedia , lookup

History of Nashville, Tennessee wikipedia , lookup

East Tennessee Convention wikipedia , lookup

Kentucky in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Jubal Early wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Conclusion of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Western Theater of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Pillow wikipedia , lookup