* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Introduction to the US Constitution and Criminal Justice System

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

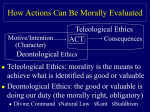

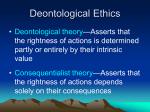

Deontological Ethics Imagine that you are on a sinking ship. You and eight other passengers manage to make it on to a lifeboat and begin heading to shore. The problem is, the lifeboat only supports eight passengers, and including you, there are nine passengers. You have to make a decision to either throw one passenger overboard and save the other eight people, or let all nine people drown. What do you do? This type of question belongs to the study of moral philosophy, or ethics. Even though most people will never find themselves in the situation described above, they do encounter situations in which they have to choose between two undesirable outcomes. For example, suppose you discovered that your boss was committing tax fraud by not reporting a portion of your company’s revenue to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). You know that this is wrong, but you also know that if you try to stop it that you would be risking your own job. Suppose that you are barely making ends meet as it is, and that you have got three children to support. You have an obligation to take care of your family, but you also have an obligation to be an honest person. How do you know what is right? Deontological (duty-based) ethics would probably say that you should tell the authorities about the tax fraud, regardless of the consequences. That is because a deontological argument says that a moral action is valuable in itself, regardless of its result. Stated another way, deontological ethics claims that the ends (the ultimate goal) do not justify the means (the way of getting to that ultimate goal). Being honest is the right thing to do for its own sake, regardless of the outcome. Deontological rules come from an authority, and those rules are to be obeyed without qualification or explanation. A classic example of a deontological morality is the Ten Commandments. The Judeo-Christian world regards the Ten Commandments as absolute moral law for no other reason than that God commands it be so. On a smaller scale, parents often employ a deontological argument with their children. When a child breaks a rule, the parent admonishes them, the child protests by asking "why?" and the parent responds “because I said so.” In this case, the parent is the authority and the rules are the rules—they do not need to be explained. Immanuel Kant called this kind of order a categorical imperative, or an order that is given without reason or condition. Categorical imperatives can be given by a wide range of external authority figures, such as God, a king, a president, the government, a local religious leader, or even parents. People 1 Deontological Ethics obey a rule because it is the law, because it is the will of God, or because that is what their mothers taught them. Reference Kant, Immanuel. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://philosophy.lander.edu/ethics/ethicsbook/c3612.html 2