* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Overwhelming Parasitemia with Plasmodium falciparum Infection in

Dirofilaria immitis wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Anaerobic infection wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Mass drug administration wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

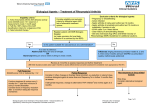

BRIEF REPORT Overwhelming Parasitemia with Plasmodium falciparum Infection in a Patient Receiving Infliximab Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis Estella M. Geraghty,1 Bryan Ristow,3 Shelley M. Gordon,2,3 and Paul Aronowitz3 1 Department of Internal Medicine, University of California Davis, Sacramento; and Departments of 2Infectious Diseases and 3Internal Medicine, California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco, California We describe a 45-year-old woman receiving infliximab therapy for rheumatoid arthritis who developed an overwhelming Plasmodium falciparum infection with cerebral malaria. Physicians should be aware that patients receiving tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, such as infliximab, may be at increased risk of life-threatening malarial infections. Despite recent enthusiasm for TNF inhibitors as disease-modifying agents for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, concern remains about their potential to suppress important aspects of the immune system. The TNF inhibitors (i.e., etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab) have been lauded for their efficacy in reducing the signs and symptoms of disease and increasing functional status. Although initial studies indicating the safety of these agents were reassuring, the studies included !1000 participants [1]; therefore, the risk of infrequent adverse reactions may have been underrepresented [2]. Of particular concern is the increased rate of intracellular infections associated with these drugs; tuberculosis risk has been most well publicized, but risk exists for other granulomatous diseases, as well as for infections with Salmonella, Listeria, and Legionella species [3]. The incidence of pyogenic skin and soft-tissue infections has also increased. Little is known, however, about the role of TNF inhibitors for treatment of malaria. Case report. A 45-year-old intensive care unit (ICU) nurse presented to the emergency department 4 days after returning Received 20 October 2006; accepted 30 January 2007; electronically published 2 April 2007. Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Estella M. Geraghty, Dept. of Internal Medicine, University of California Davis, 4150 V St., PSSB 2400, Sacramento, CA 95817 (Estella [email protected]). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007; 44:e82–e84 2007 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. All rights reserved. 1058-4838/2007/4410-00E2$15.00 DOI: 10.1086/515402 e82 • CID 2007:44 (15 May) • BRIEF REPORT from a vacation in Mali, Africa. Her past medical history was notable only for rheumatoid arthritis. She had received 1 dose of methotrexate 1 month prior to her vacation, and she was receiving weekly injections of infliximab. While in Mali, the patient used mosquito netting and mosquito repellent, but she chose not to take malaria chemoprophylaxis, although it had been recommended by her physician. The day after her return to the United States, the patient developed a fever (temperature, 40.3C), which was initially treated at home with acetaminophen. In the emergency department, the patient complained of headache, dizziness, anorexia, myalgias, and fever with drenching sweats. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing woman with a temperature of 39.0C and an oxygen saturation by pulse oximeter of 97%. She was awake and alert and had no evidence of neurologic abnormalities. There were no rashes or petechiae. Laboratory data revealed a WBC count of 4700 cells/mL, with 55% neutrophils and 32% band forms. The platelet count was 21,000 platelets/mL, hematocrit was 38%, and a blood smear (figure 1) revealed Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasitemia. On the night of hospital admission, the degree of parasitemia was not quantitated; upon later review of blood smears, it was estimated to be 150%. The blood urea nitrogen level was 15 mg/dL, the creatinine level was 0.7 mg/dL, the total bilirubin level was 1.9 mg/dL, the aspartate aminotransferase level was Figure 1. The patient’s thin blood smear revealing the characteristic intraerythrocytic ring forms (trophozoites) associated with Plasmodium falciparum infection. Note both the overwhelming degree of parasitemia and the paucity of platelets. Wright Giemsa stain with oil immersion original magnification, ⫻100. 71 U/L, the alanine aminotransferase level was 50 U/L, the ionized calcium level was 4.0 mg/dL, the d-dimer level was 401 ng/mL, the fibrinogen level was 259 ng/mL, and the international normalized ratio was 1.1. The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment of P. falciparum infection with quinine sulfate and doxycycline, which she was able to take orally. Twelve h after admission, the patient developed slurred speech and had difficulty constructing sentences. Examination revealed weakness of the left upper extremity and left ptosis. CT of the brain exhibited no acute pathology; a diagnosis of cerebral malaria was made. The patient was transferred to the ICU for closer monitoring. Within 2 h of transfer to the ICU, the patient’s mental status declined further, and she had a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. She underwent intubation for airway protection, and phenytoin therapy was initiated. Quinine and doxycycline therapies were continued via nasogastric tube. Thirty-six h after admission, the patient’s hematocrit decreased to 26%, and the overall degree of parasitemia on her blood smear decreased to 4.6%. She received an RBC exchange transfusion with 8 U of packed RBCs. A blood smear performed a few hours after the procedure revealed a further reduction of her parasitemia to !1%. The patient’s mental status improved over the next 3 days, and she underwent extubation. After 9 days of hospitalization, the patient was discharged. At that time, she was afebrile and had mild gait instability and residual left-side ptosis. Phenytoin therapy was discontinued. Over the next month, with ongoing physical, occupational, and speech therapy, the patient achieved complete neurologic recovery, with resumption of her normal activities. She subsequently returned to her job as an ICU nurse. Discussion. Malaria parasites live and divide inside erythrocytes. In the process, they alter the RBC membrane, making it subject to splenic clearance and hemolysis. The rupture of RBCs leads to a release of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-a. TNF-a appears to have many roles in the pathophysiology of malarial infections, but precise mechanisms are not well understood. At lower levels, TNF-a has a pleiotropic antimalarial effect and, thus, is beneficial for fighting infection. However, at higher levels, its effect may be detrimental [4, 5]. Higher levels of TNF-a may cause increased vascular release of nitric oxide, causing interference with neurotransmission and vasodilation, a process thought to increase the risk of cerebral edema [4]. In cerebral malaria, sequestration of parasites in the microvasculature is believed to lead to local production of inflammatory mediators, including TNF-a, leading to upregulation of glycoproteins, such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1. This, in turn, leads to further sequestration [6]. Administration of antibodies against TNF-a for treatment of cerebral malaria has not been found to affect mortality [7]. Recently, an in vitro model suggested that LMP-420, an inhib- itor of TNF mRNA, strongly inhibits endothelial adhesiveness for P. falciparum–infected RBCs and inhibits the release of endothelial microparticles [8]. This approach has yet to be shown effective in clinical trial. The addition of TNF inhibitors to the armamentarium of medications used to treat rheumatoid arthritis has revolutionized the treatment of the disease. Because these agents successfully inhibit the progression of structural damage, a more aggressive early approach has become routine [9]. However, these agents also affect host immunity, disrupting the cell-mediated immune response to intracellular pathogens [10]. There is a clear association between the TNF inhibitors (especially infliximab) and increased risk of opportunistic infections, such as tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, listeriosis, and Pneumocystis [11]. To our knowledge, increased risk of severe P. falciparum infection, including cerebral malaria, has not previously been reported. We believe that the overwhelming P. falciparum parasitemia and cerebral malaria seen in this patient may have been associated with her use of infliximab for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Although it may be argued that her use of methotrexate 1 month prior to her infection confounds this association, we make the following 3 points: (1) the pharmacokinetics of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis reveal a terminal half-life of 6 h [12], indicating that drug effects are minimal after 30 days; (2) the risk of infection is higher for patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab plus methotrexate, compared with methotrexate alone, suggesting that the higher incidence of serious infection is attributable to infliximab [13, 14]; and (3) the role of TNF-a for treatment of malaria provides a plausible biologic explanation for the severe level of parasitemia experienced by this patient. Although we attribute this patient’s high degree of parasitemia and cerebra malaria to her recent use of a TNF-a inhibitor, one might speculate that our patient’s lack of manifestations of severe malaria, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, and even her salutary recovery might have been a result of a protective effect of TNF inhibition. TNF inhibitors provide proven efficacy for the management of an often refractory rheumatologic disease, and patients will likely benefit from increasing use of TNF inhibitors in the future [10]. Unfortunately, these disease-modifying agents also appear to increase the frequency and severity of certain infections [11]. We report a case of overwhelming P. falciparum parasitemia with cerebral malaria in a 45-year-old woman undergoing treatment with infliximab for rheumatoid arthritis. It is imperative that clinicians are aware of the possibility of life-threatening malaria infections associated with infliximab. The importance of appropriate recommendations for malaria chemoprophylaxis for patients traveling to regions where malaria is endemic cannot be overemphasized. BRIEF REPORT • CID 2007:44 (15 May) • e83 Acknowledgments Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no conflicts. References 1. Schaible T. Long term safety of infliximab. Can J Gastroenterol 2000; 14(Suppl C):29C–32C. 2. Kavanaugh A, Keystone EC. The safety of biologic agents in early rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003; 21(Suppl 31):S203–8. 3. Symmons DP, Silman A. The world of biologics. Lupus 2006; 15:122–6. 4. Malaguarnera L, Musumeci S. The immune response to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet Infect Dis 2002; 2:472–8. 5. Akanmori B, Kurtzhals JA, Goka BQ, et al. Distinct patterns of cytokine regulation in discrete clinical forms of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Eur Cytokine Netw 2000; 11:113–8. 6. Hunt NH, Grau GE. Cytokines: accelerators and brakes in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Trends Immunol 2003; 24:491–9. 7. Kwiatkowski D, Molyneux MD, Stephens S, et al. Anti-TNF therapy inhibits fever in cerebral malaria. Q J Med 1993; 86:217–8. e84 • CID 2007:44 (15 May) • BRIEF REPORT 8. Wassmer SC, Cianciolo GJ, Combes V, Grau GE. Inhibition of endothelial activation: a new way to treat cerebral malaria? PLoS Med 2005; 2:e245. 9. Haraoui B. The anti-tumor necrosis factor agents are a major advance in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl 2005; 72: 46–7. 10. Rychly DJ, DiPiro JT. Infections associated with tumor necrosis factora antagonists. Pharmacotherapy 2005; 25:1181–92. 11. Crum NF, Lederman ER, Wallace MR. Infections associated with tumor necrosis factor-a antagonists. Medicine 2005; 84:291–302. 12. Herman R, Veng-Pedersen P, Hoffman J, Koehnke R, Furst DE. Pharmacokinetics of low-dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Pharm Sci 1989; 78:165–71. 13. Listing J, Strangfeld A, Kary S, et al. Infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52:3403–12. 14. St. Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS, et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:3432–43.