* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Drug utilization and medication costs at the end of

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

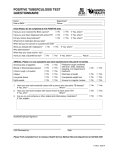

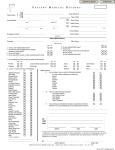

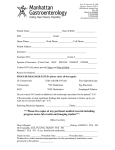

Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research ISSN: 1473-7167 (Print) 1744-8379 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ierp20 Drug utilization and medication costs at the end of life Lisa Pont, Kristian Jansen, Margrete Aase Schaufel, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen & Sabine Ruths To cite this article: Lisa Pont, Kristian Jansen, Margrete Aase Schaufel, Dagny Faksvåg Haugen & Sabine Ruths (2016) Drug utilization and medication costs at the end of life, Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 16:2, 237-243, DOI: 10.1586/14737167.2016.1158106 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/14737167.2016.1158106 Accepted author version posted online: 26 Feb 2016. Published online: 25 Mar 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 32 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ierp20 Download by: [University of Technology Sydney] Date: 12 April 2016, At: 01:07 EXPERT REVIEW OF PHARMACOECONOMICS & OUTCOMES RESEARCH, 2016 VOL. 16, NO. 2, 237–243 http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/14737167.2016.1158106 REVIEW Drug utilization and medication costs at the end of life Lisa Ponta, Kristian Jansenb,c, Margrete Aase Schaufelb,d, Dagny Faksvåg Haugene,f and Sabine Ruthsb,c Downloaded by [University of Technology Sydney] at 01:07 12 April 2016 a Centre for Health Systems and Safety Research, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University, North Ryde, Australia; bResearch Unit for General Practice, Uni Research Health, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; cDepartment of Global Public Health and Primary Care, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; dDepartment of Thoracic Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway; eRegional Centre of Excellence for Palliative Care, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway; fDepartment of Clinical Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY In the end stages of life, drug treatment goals shift to symptom control and quality of life and as such changes in drug utilization are expected. The aim of this paper is to review the extent to which costs are considered in drug utilization research at the end of life, with a particular focus on the outcome measures being used. This systematic review identified seven studies across varied settings studies reporting both drug utilization and medication cost outcome measures. The main factors identified that impacted medication use and cost were the time period considered and the provision of specialist palliative care services. Combining drug utilization and medication cost outcomes is critical for the allocation of healthcare resources and the development of a sound health policy. Received 12 January 2016 Accepted 22 February 2016 Introduction Increasing expenditure on medications represents an ongoing challenge to many health systems [1]. The U.S. annual expenditure on medications was estimated at over $440 billion in the year 2015 and is expected to reach over $700 billion by 2020 [2]. Understanding current patterns in medication use and the related impact on medication expenditure is critical for allocation of health care resources and development of sustainable health policy. Drug utilization research provides insight into the way medications are used within society, with emphasis on the medical, social and economic consequences [3]. Drug utilization research is currently used to assess quality use of medicines, to identify areas of suboptimal medication use, to provide feedback to prescribers and to benchmark medication use within and between settings [4]. Internationally, there is a focus on the provision of quality medical care throughout the entire continuum of life, including at the end of life. It is generally acknowledged that medical management at the end of life should focus on optimizing quality of life and minimizing symptoms, rather than on extending the duration of life [5]. Such a shift in treatment goals from preventative and curative care to symptomatic care will impact the drug therapy used during the end-of-life period, requiring changes to the types, formulations, administration routes and doses of medications used. Specialized palliative care services may oversee such changes for those patients referred to their care; however, limitations in access to palliative care services mean that end-of-life care for many patients is managed outside of these specialized services. Drug utilization research into the use of medications at the end of life has shown increases in the use of medicines for CONTACT Lisa Pont [email protected] © 2016 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group KEYWORDS End-of-life; drug utilization; systematic review; palliative care; medication costs symptom control [6], yet little is known about the impact these changes have on medication utilization and medication-related expenditure. Inclusion of cost-related outcomes in drug utilization studies would allow insight into the relationship between medication utilization and medication expenditure at the end of life. However, it is unknown to what extent drug utilization research at the end of life includes cost outcomes and which drug utilization and medication cost-related outcomes are currently used when studying this population. Therefore, the aim of this study was to review the extent to which costs are considered in end-of-life drug utilization research, with a particular focus on the medications included and the utilization and cost outcome measures used. Methods A systematic review following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement was conducted across six electronic databases using a search strategy modified from that published in the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance: Care of the dying adult [7]. Medline, Embase, Cochrane central register of controlled trials, Cochrane database of systematic reviews, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) and PsycINFO were searched using a combination of the terms ‘death’, ‘terminally ill’, ‘palliative care’, ‘hospice care’, ‘end-of-life’, ‘drug therapy’ and ‘cost’. The full search strategy is available in Appendix 1. Studies were included in the review if they focused on endof-life care, reported both drug utilization and medication cost outcomes, were written in English, and to increase relevance for current practice, were published in the past 20 years, that is, between 1995 and 2015. Conference abstracts, case reports, 238 L. PONT ET AL. opinion pieces and editorials and clinical treatment guidelines were excluded from the review. Data were extracted from full text papers by a single researcher (Lisa Pont) using a standardized data extraction form. The data extracted included study characteristics (country, year, population, aim and sample size), drug utilization measures (drug agents or class and drug utilization outcome measure) and medication cost outcome. Identification The search strategy identified 410 studies (Figure 1), of which seven met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (Table 1) [8–14]. While the studies were conducted across a variety of countries, the highest number of the included studies were conducted in Europe (n = 3). While all of the included studies reported drug utilization and medication cost-related outcomes, the aims of the studies were diverse. Only one study aimed to examine drug utilization and related costs at the end of life [8]. Fahlman et al. found that medication costs at the end of life varied depending on the cause of death. Medline Embase (n = 50) (n = 382) Cochrane trials (n = 1) CINAHL Psychinfo (n = 20) (n = 15) Eligibility Screening Records after duplicates removed (n = 410) Included Downloaded by [University of Technology Sydney] at 01:07 12 April 2016 Results Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes had the highest medication utilization and costs prior to death. However, this study reported only aggregated medication costs and did not provide information on utilization or costs associated with individual medications or classes. Most studies (n = 6) were conducted retrospectively [8,9,11–14]. Only the Finnish study examining the quality of pain control at the end of life was conducted prospectively [10]. This was a small observational study with 36 participants, focused on the last 2 weeks of life. Despite all studies focusing on the end-of-life period, there was great diversity in the time before death that was considered ‘end of life’. Tavčar et al. examined drug utilization over the last 6 days of life, Hinkka et al. examined the last week and last 24 hours, Silvera et al. and Gaertner et al. examined the last 6 months and Fahlman et al. reported on use during both the last month of life and the last year of life. The importance of including time or proximity to death in drug utilization studies was highlighted by Moore, Bennet and Norman [12]. In a retrospective case–control study using National data from the New Zealand Ministry of health pharmacy claims for over 40,000 older residents, they showed that Figure 1. Search and study selection. Records screened for title and abstract (n = 410) Records excluded after title and abstract screening (n = 366) Full-text articles assessed for eligibility (n = 44) Full-text articles excluded, (n = 37) No medication cost data (n=18) No drug utilization data (n=12) Not end of life (n=2) Case study (n=1) Editorial, opinion piece or treatment guideline (n=4) Studies included in qualitative synthesis (n = 7) 1998– 2000/US$ 2013/€ 2001€ 2013 US$ 2014NZ$ 2008US$ 2014€ Fahlman et al. [8] (USA) Gaertner [9] (Germany) Hinkka [10] (Finland) Hwang [11] (Taiwan) Moore [12] (New Zealand) Silvera [13] (USA) Tavčar et al. [14] (Slovenia) BARMER GEK Health insurance beneficiaries/ claims data Medicare beneficiaries/ claims data Population/data type 11,355 4602 Patients with a life-limiting 1584 illness receiving care at Veterans Integrated Service Network facilities using a statin/pharmacy supply data To identify differences in use Patients with incurable 50 of drugs among terminally advanced cancer who ill patients receiving died at the Institute of palliative care versus Oncology/inpatient standard care medical records To measure the prevalence of statin use during the last 6 months of life To assess the quality of Patients admitted with 36 cancer pain control during terminal cancer during the last week of life in two 1998/inpatient medical different types of units for records terminal cancer patients in Finland To compare the National health insurance 3236 characteristics of patients, beneficiaries with cancer medical procedures, who died during the prescriptions and study period/claims data expenses between hospice and usual care To examine the effect of age Residents aged 70 years 40,322 and proximity to death on and older present in the medication use and cost New Zealand Ministry of Health Pharmacy claims data/pharmacy supply data Effect of palliative care on patient care during last 6 months of life To examine drug spending by disease and demographics in the last year of life Aim Sample size Retrospective case control 6 days 6 months 12 months Retrospective case control Retrospective case control Not stated 1 week 6 months 12 months End-of-life period (time prior to death) Retrospective observational Prospective observational Retrospective case control Retrospective observational Study design Some comparative data are presented for nervous system medications, but total use for each group is not presented. § Year/currency Author (country) Table 1. Study characteristics and summary of findings. Downloaded by [University of Technology Sydney] at 01:07 12 April 2016 Top seven most frequently prescribed drug classes Number of participants prescribed each medication class Number of drugs per person Mean number of prescriptions filled Drug utilization outcome Medication cost outcome Cost for drugs over 6 days Average cost for drugs per person per day Mean out-of-pocket cost Mean amount paid by insurer Mean amount claimed by pharmacy Opioids The proportion of Total inpatient patients who medication costs received at least one dosage of opioids The mean defined daily dose (DDD) of opioids Opioids DDDs of pain Cost of daily pain medications medication 7 days Proportion of and 24 h prior to patients death receiving strong opioids Top 10 Percentage of Mean cost per medication patients patient per day classes used in prescribed each setting each medication class Number of items Expenditure per Not specified§ per individual individual Total annual expenditure Median expenditure per individual Average expenditure per prescriptions Statins Number of days Total cost of statin of statin use therapy prior to death Not specified Pharmacological agent and/or class EXPERT REVIEW OF PHARMACOECONOMICS & OUTCOMES RESEARCH 239 240 L. PONT ET AL. drug utilization and expenditure vary in the last month of life depending on age. Patients in their last month of life used almost twice as much medication as age-matched survivors. However, while expenditure among controls increased with age, expenditure for those in the last month of life decreased with age. Hinkka et al. observed and reported that medication expenditure for daily pain medication increased in the last week of life [10]. Downloaded by [University of Technology Sydney] at 01:07 12 April 2016 Medications included There was variation in the medications included in each of the studies. Opioids were the focus of two studies, the small (n = 36) prospective Finnish study [10] and the much larger (n = 11,355) German study [9]. Despite difference in sample size and design, both studies reported similar finding that patients receiving specialist palliative care services were more likely to receive opioids than those receiving standard care and that the doses of opioids received were 2–4 times higher in palliative care than in standard care. Hinkka et al. also showed differences in the choice of opioids, with standard care patients receiving parenteral morphine earlier than those with palliative care (percentage of users at 1 week prior to death 20 vs. 0%, p = 0.021). One study focused on the use of statins at the end of life [13], and two explored overall drug utilization [11,14], generally reporting the most frequently prescribed medications. In both papers, looking at most frequently used medications, opioids were the most commonly used agent followed by laxatives in the Slovakian paper [14] and electrolyte fluids in the Taiwanese paper [11]. Drug utilization outcomes The data sources used in the different studies impact on the aspect of drug utilization measured. Three studies used health insurance claims data. Claims data provide information on medications received by a patient that were funded by a specified third-party payer [8,9,11]. Two studies used medication data recorded in patient hospital medical records [10,14], while two studies used pharmacy medication supply data [12,13]. Three main drug utilization outcome measures were reported in the studies. Three studies[9–11] reported on the number or percentage of patients who received each medication or drug class, three studies[8,12,14] reported the number of medications or items per patient, and two studies [9,10] reported the mean defined daily dose [3,15] (DDD) per patient. Three studies [9,10,14] used multiple drug utilization measures, in two cases a combination of the proportion of patients receiving a medication and the DDDs being used and in one case a combination of the proportion receiving the medication and the number of medications per patient. Interestingly, the two studies that reported DDDs as a drug utilization outcome measure were both focused on the use of opioids. Medication cost-related outcomes There was variation in the medication cost outcome measures reported. While total medication cost per patient was the most commonly used outcome measure, different studies focused on cost from different perspectives. Gaertner et al. reported total inpatient pharmacy costs but did not clarify if these were only medication-related costs or if they included other costs such as pharmacy labor as well [9]. This study was also unable to include outpatient or ambulatory medication costs, as these were not captured in the health insurance data set used for their analysis. Hwang et al., Moore, and Tavčar et al. reported cost per patient but did not indicate what was included in these costs [11,12,14]. Fahlman et al. reported costs from a third-party payer perspective using mean out-of-pocket costs, mean cost to the insurer and mean amount claimed by the pharmacy [8]. Factors affecting drug utilization and expenditure The type of care provided was shown to have a significant impact on both drug utilization and related medication costs. Four studies examined differences in the provision of specialist palliative care at the end of life versus usual care [9–11,14]. All four studies used retrospective designs and reported differences in drug utilization and medication costs between the types of care provided. Care issued by specialist palliative care providers or settings was associated with lower medication costs. There were distinct differences observed in the types of medications used between the different care providers. Both the Taiwanese and the Slovakian studies reported much higher use of antibiotics and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) for patients receiving standard care compared to those receiving palliative care, which may account for the increased medication expenditure. In the Taiwanese study, 80% of patients receiving usual care received TPN and 61% received cephalosporin antibiotics, which may account for the 4× higher medication costs observed with standard care. However, like most of the studies included in this review, only aggregate drug costs were provided with drug costs for individual drug classes not provided. Discussion This systematic review explored the extent to which costs are considered in end-of-life drug utilization research, with a particular focus on the outcome measures being used. Seven studies published in the past two decades were identified that reported both drug utilization outcomes and medication-related cost outcomes. While all studies considered medication use among end-of-life populations, there was considerable variation in the drug utilization and cost-related outcomes used, as well as in the period considered the end of life. Drug utilization research has traditionally utilized a range of outcome measures. There is a need for different outcome measures, which depend upon the question being researched [3]. Such diversity, however, makes comparing between Downloaded by [University of Technology Sydney] at 01:07 12 April 2016 EXPERT REVIEW OF PHARMACOECONOMICS & OUTCOMES RESEARCH studies challenging. In our review, three main drug utilization outcome measures were used: proportion of the population using a particular medication, the dose measured in DDDs of the medication being used and the number of medications or items used per person. Each of these provides information regarding a different aspect of medication use. Proportion of the population of interest receiving a particular medication provides information regarding the extent of medication use, while information on the dose being used, measured through the World Health standardized DDD methodology [15], allows interpretation of the amount of medication used at the individual patient level. Both outcome measures, the extent of use and the amount being used, should be used together to assess quality of care and allocate resources. Using information on medication costs in combination with drug utilization data is important when allocating resources or developing health policy. A number of medication cost outcomes have been proposed for use with drug utilization data, and again, the choice of metric will depend upon the purpose of the analysis. Interpretation of medication-related cost outcomes depends on the perspective from which the costs are being allocated. Costs may be considered from the perspective of the government, health facility or setting, health care provider, insurer or other third-party payer or from the patient. In our review, the majority of studies did not provide adequate information regarding the perspective from which costs were determined. The perspective from which costs were being determined was described in only one study. Fahlman et al. used a combination of three cost outcome measures measuring cost from three different perspectives: the patient-mean out-of-pocket costs, the insurer-mean amount paid by the insurer and the health facility-mean amount claimed by the pharmacy [8]. The combination of these three measures allows the full implication of changes in drug utilization to be assessed across for all relevant payers. Medication costs per individual was used as an outcome measure in six of the studies, with three of these looking at medication cost per individual and three looking at total medication costs. In this review, two studies focused on the utilization of opioids used such a combination. The aim of both studies was to evaluate the impact of specialist palliative care services [9,10]. While these services are associated with increased total health care costs, the drug utilization data presented indicates that patients treated using these services were more likely to receive opioid analgesics in higher doses, which may equate differences in the level of pain, improved pain management and quality of life. Analysis of the medication cost outcomes shows that despite overall increased health outcomes, medication-related costs are actually lower in specialized palliative care services when compared to usual care [16,17]. Interpretation of the third drug utilization outcome measure used, number of items or number of prescriptions per patient, in the end-of-life context is more problematic. While this outcome measure may facilitate interpretation of expenditure data, allowing insight into the spread of medication use among a particular population, without accompanying medication cost-related data, such a measure is difficult to interpret. Simply looking at the number of medications used by a patient does not provide information on the appropriateness 241 of use, and while research has indicated overuse of inappropriate medications at the end of life [13,18,19], simply measuring the number of medications used does not provide any indication about the need or expected benefit associated with their use. Understanding the data source used in drug utilization studies is an important consideration in interpreting the results of drug utilization outcomes; yet, these differences may be less relevant for the interpretation of associated costs. Drug utilization research encompasses marketing, prescription, supply and use of medications in society, and knowing which aspect of utilization is being considered in a particular drug utilization study is critical [3]. In studies using medication supply data, such as claims or dispensing data, it is known that the patient receives the drug, but it is not known if they actually utilize it. With the use of prescribing records as a data source, it is known that the doctor wishes the patient to use the medication but actual use by the patient is unknown, while with administration data, actual medication use can be determined. Generally, such differences in data have considerable implications for interpretation of drug utilization studies; however, these differences may be less when medication costs are considered, as it is receipt of the medication by the patient that becomes the critical factor. In this review, two factors were found to impact medication costs and utilization at the end of life. The first was proximity to death or the length of the time period studied. Moore, Bennet and Norman showed that proximity to death had a significant effect on medication expenditure among older communitydwelling people [12]. Medication utilization and expenditure at the end of life decreased with age, with those who died at the age of 90 years or older consuming fewer drugs than those who died in their 70s and 80s. Interestingly, similar decreases have been shown for medication use by older adults in primary care who are not at the end of life [20]. Differences in what is considered the end of life are well documented [21–26]. A study in 2013 of 167 health professionals and academics working in 19 countries found that there was no agreement regarding what was considered end-of-life care [21]. In the studies included in our review, there was great diversity in the time period considered to be ‘end of life’ over which medication utilization and costs were examined. The time periods included ranged from the last 24 h of life to the last year of life, making comparison of drug utilization patterns between the studies impossible. Differences in care services provided, availability of specialized palliative services as well as the reason for death and comorbid conditions will all contribute to differences in medication utilization during the end-of-life period. Provision of specialist palliative care was associated with differences in drug utilization and medication costs. Best practice for endof-life care acknowledges the importance of symptom management and quality of life measures rather than the provision of active life-prolonging treatment [27]. Provision of specialist palliative care services has been shown to improve quality of life, patient and provider satisfaction, and decrease hospitalizations at the end of life [16,17]. Four of the studies included in our review examined the impact of specialist palliative care services on medication utilization and medication costs. 242 L. PONT ET AL. Downloaded by [University of Technology Sydney] at 01:07 12 April 2016 Palliative care services in all four studies were associated with changes in drug utilization that are consistent with increased use of symptom-controlling medications and decreased medication expenditure [9–11,14]. One of the main limitations to this systematic review was the diversity of terminology used to describe the end-of-life period as discussed previously. To minimize this, we used a previously published search strategy that was developed by the U.K. National Institute of Clinical Excellence as part of their consultation process for their guidance on Care of the dying adult [7]. Following the public consultation process, the focus of the guidance document changed to care of the dying adult in the last few days of life; however, this time limitation was not reflected in the original search strategy, and hence, the original search strategy remains relevant to our research question [28]. Conclusion A variety of drug utilization and medication costs outcomes are used in end-of-life research; however, the total number of studies reporting both drug utilization and medication costs at the end of life was small. While medication cost data provide insight into total expenditure and may be useful for resource allocation, changes in drug costs may result from multiple changes in drug utilization such as changes in the agent, the amount or the cost of individual items, and use of cost data alone without the corresponding drug utilization information may be misleading. Similarly, drug utilization data without the corresponding cost outcome may be of limited benefit to policy makers and for resource allocation to end-of-life health care. Expert commentary & five-year view The world’s population is aging, and while end-of-life care is not only relevant for older populations, older persons still account for the largest population for whom such care is being provided. Demands on resources for end-of-life care will see huge increases in the coming 5 years. The challenge for clinicians and policy makers alike is the provision of high quality end-of-life care in resource-limited environments. Drug utilization studies provide insight into how medicines are used within society, while pharmacoeconomic evaluations have tended to focus on costs associated with individual medicines or conditions. Consideration of both utilization and expenditure patterns is needed for development of robust health policy and provision of quality health care. This review highlights the lack of studies on medicine use at the end of life integrating both utilization and cost outcomes. End-of-life research incorporating utilization and cost outcomes is desperately needed to guide future policy and care in this critical area. Key Issues ● Changes in medication utilization are expected during endof-life care. Treatment goals shift to minimizing symptoms and improving quality of life rather than prolonging life. ● Drug utilization studies provide insight into the way medicines are used across society, allowing assessment of the quality of care as well as providing information to guide resource allocation and health policy development. ● Robust health policy and provision of quality end-of-life care require drug utilization and associated medication cost data, yet little is known regarding the use of medication-related cost outcomes in drug utilization research. ● There are few studies reporting both drug utilization and related medication cost outcomes at the end of life. ● In the seven studies reporting both end-of-life medication utilization and cost outcomes, there was variation in the outcome measures used, making direct comparisons between the studies difficult. Financial & competing interests disclosure L Pont is partially funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Translating Research into Practice Fellowship. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. References 1. Luiza VL, et al. Pharmaceutical policies: effects of cap and copayment on rational use of medicines. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;5:CD007017. 2. Daemmrich A, Mohanty A. Healthcare reform in the United States and China: pharmaceutical market implications. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2014;7(1):9. 3. World Health Organization. Introduction to drug utilization research. Oslo, Norway: WHO International Working Group for Drug Statistics Methodology, WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Utilization Research and Clinical Pharmacological Services; 2003. 4. Wettermark B. The intriguing future of pharmacoepidemiology. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(Suppl 1):43–51. 5. Lamont EB. A demographic and prognostic approach to defining the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):S12–21. 6. Masman AD, et al. Medication use during end-of-life care in a palliative care centre. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(5):767–775. 7. National Clinical Guideline Centre. Care of the dying adult. (draft for consultation 29 July 2015). Manchester: NICE; 2015. 8. Fahlman C, et al. Prescription drug spending for Medicare+Choice beneficiaries in the last year of life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(4):884–893. 9. Gaertner J, et al. Inpatient palliative care: a nationwide analysis. Health Policy. 2013;109(3):311–318 8. 10. Hinkka H, et al. Assessment of pain control in cancer patients during the last week of life: comparison of health centre wards and a hospice. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2001;9(6):428–434. 11. Hwang SJ, et al. Hospice offers more palliative care but costs less than usual care for terminal geriatric hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a nationwide study. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(7):780–785. 12. Moore PV, Bennett K, Normand C. The importance of proximity to death in modelling community medication expenditures for older people: evidence from New Zealand. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 2014;12(6):623–633. 13. Silveira MJ, Kazanis AS, Shevrin MP. Statins in the last six months of life: A recognizable, life-limiting condition does not decrease their use. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):685–693. 14. Tavčar P, et al. Drugs and their costs in the last six days of life: A retrospective study. Eur J Oncol Pharm. 2014;8(2):19–23. 15. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; 2015. Downloaded by [University of Technology Sydney] at 01:07 12 April 2016 EXPERT REVIEW OF PHARMACOECONOMICS & OUTCOMES RESEARCH 16. El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS. Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(3):87–94. 17. Rabow M, et al. Moving upstream: a review of the evidence of the impact of outpatient palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16 (12):1540–1549. 18. Heppenstall CP, et al. Medication use and potentially inappropriate medications in those with limited prognosis living in residential aged care. Australas J Ageing. 2015. doi:10.1111/ajag.12220. [Epub ahead of print] 19. Ma G, Downar J. Noncomfort medication use in acute care inpatients comanaged by palliative care specialists near the end of life: a cohort study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(8):812–819. 20. Vegda K, et al. Trends in health services utilization, medication use, and health conditions among older adults: a 2-year retrospective chart review in a primary care practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:217. 21. Gysels M, et al. Diversity in defining end of life care: an obstacle or the way forward? PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68002. 22. Hui D, et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):659–685. 23. Hui D, et al. The lack of standard definitions in the supportive and palliative oncology literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43 (3):582–592. 24. Hui D, et al. Concepts and definitions for “actively dying,” “end of life,” “terminally ill,” “terminal care,” and “transition of care”: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(1):77–89. 25. Sade RM. Introduction. Defining the beginning and the end of human life: implications for ethics, policy. And Law. J Law Med Ethics. 2006;34(1):6–7. 26. Thompson G, McClement S. Defining and determining quality in end-of-life care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2002;8(6):288–293. 27. American Academy of, H., et al. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for quality palliative care, executive summary. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(5):611–627. 28. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Care of dying adults in the last days of life. Clinical Guideline 31. London: NICE; 2015. (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17) (18) (19) (20) (21) (22) (23) (24) (25) (26) (27) (28) (29) (30) (31) (32) (33) (34) Appendix 1 Search strategy (35) End-of-life drug therapy and cost review – search strategy in Ovid MEDLINE: (36) (37) (38) (39) (1) Death/(12476) (2) Terminally ill/(5725) 243 Terminal care/or hospice care/(26880) Palliative care/(43279) Palliative medicine/(49) ‘Hospice and palliative care nursing’/(150) (dying or die* or death).ti,kf. (301172) ((terminal or palliati*) adj1 care).ti,kf. (11287) (‘terminally ill’ or ‘terminal illness’).ti,kf. (2132) (palliati* adj1 stage*).ti,ab. (359) (‘end-of-life’ adj2 (stage or stages)).ti,ab. (49) or/1–11 (364700) ‘end-of-life’.ti,ab. (13908) ((last or final) adj1 (hour* or days* or minute* or stage* or week* or month*)).ti,ab. (14642) ((dying or terminal) adj1 phase*).ti,ab. (2030) ((dying or terminal or end) adj1 stage*).ti,ab. (51986) (dying adj2 (actively or begin* or begun)).ti,ab. (53) (death adj2 (imminent* or impending or near or throes)).ti,ab. (1564) ((dying or death) adj2 (patient* or person* or people)).ti,ab. (20683) (Body adj2 (shut down or shutting down or deteriorat*)).ti,ab. (115) (deathbed or death-bed).ti,ab. (98) or/13–21 (101137) 12 and 22 (19542) drug therapy/or drug administration routes/or drug administration schedule/or drug prescriptions/or drug therapy, combination/or fluid therapy/or home infusion therapy/or inappropriate prescribing/or medication errors/or polypharmacy/or premedication/or self administration/or self medication/(333170) drug therapy.fs. (1846732) exp Analgesics/(455564) exp anti-anxiety agents/or exp antipsychotic agents/(157583) exp Benzodiazepines/(60672) exp Antiemetics/(131824) exp Cholinergic Antagonists/(75547) exp Diuretics/(73436) (analges* or morphin* or opioid* or antiepileptic* or anticonvuls* or acetaminophen or paracetamol or NSAIDs or non-steroidal antiinflammat*).ti,ab,kf. (237984) (anti-anxiety agent* or Midazolam or anxiolytic* or diazepam or oxazepam or lorazepam or benzodiazepine*).ti,ab,kf. (60986) (anticholinergic* or anti-cholinergic* or glycopyrronium or scopolamine).ti,ab,kf. (17337) (antiemetic* or antipsychotic* or haldol or risperidone).ti,ab,kf. (39037) (diuretic* or furosemide).ti,ab,kf. (42112) or/24–36 (2651529) 23 and 37 (2109) 38 and cost (477)