* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Product Market Equation

Survey

Document related concepts

Full employment wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

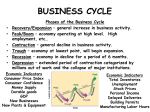

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Economic growth wikipedia , lookup

Rostow's stages of growth wikipedia , lookup

Nominal rigidity wikipedia , lookup

Fiscal multiplier wikipedia , lookup

Phillips curve wikipedia , lookup

Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory wikipedia , lookup

Inflation targeting wikipedia , lookup

Early 1980s recession wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

THE PRODUCT MARKET EQUATION: • is: x = p + q • addresses the questions: o What are the effects of changes of spending? or What happens if spending changes? o What happens if technology changes? o What happens if costs of production change? • says: Any percent change of spending must be accompanied by changes of inflation and real growth that add up to the percent change of spending. • can be used to describe how the product market responds to changes of spending, technology and costs. Derivation: X = dollars of spending = (nominal) GDP P = the price level Q = the quantity of output = real GDP x = %∆X = growth rate of nominal GDP p = %∆P = inflation rate q = %∆Q = growth rate of real GDP The Product Market Equation states the fact that the dollar amount spent (X) is equal to the price (P) times the number of units bought (Q). That is: X = P·Q. In its rate of change form, this equation becomes x = p + q. A. CALCULATING the numbers in the Product Market Equation -- x = p + q The percentage change between any two numbers, over a year’s time, is calculated by -Value in sec ond year Value in sec ond year − Value in first year OR x100% − 1 x100% Value in first year Value in first year • x = nominal GDP growth -- the percent change of spending between two years This is the “easiest” number to get. Roughly speaking, we ask every store in the country (by way of tax records, for example) how many dollars worth of goods they sold in each year. We compute the percentage difference between any two years. • p = inflation rate -- the percent change of the price level1 between two years To get this number we select a representative (“average”) selection of goods (a “basket”). We buy this same basket in consecutive years and measure the percent change of the price of this basket. We find out what percent more it costs in the second year than in the first. This is the inflation rate. This measurement has lots of problems: o It’s unclear what “average” means. Different people buy very different combinations of goods. o It’s impossible to keep the contents of the basket typical of real consumption, without changing its contents occasionally, but this defeats the concept of buying the same goods so as to compare only price changes. We problem can be stated as whether you want the “basket” to be “current” or to be “constant.” 1 . The price level can be thought of as “the cost of living.” Section D. The Product Market Equation. page 1 Macroeconomics, Kvaran o This process does not work well when the quality of the goods in the basket changes. The cars we drive, the computers we use and the medical care we get are all quite different than they were not long ago. So even if we keep a computer in the basket, it is hard to account for the fact that this year’s computer is different from last year’s. • q = real growth rate -- the growth rate of real GDP. This is intended to measure how much more real “stuff” we have than we did a year ago. This is computed by using the Product Market Equation in the form q = x - p. Once we have x and p we can calculate q. For example, if we spent 7% more than we did last year (x = 7) and if 3% percent of that went to pay higher prices (p = 3%), then we must have bought 4% more “stuff” than we did the year before. Notice a problem. If we are unsure about how well we measured inflation (p), then we have to be equally uncertain about the number for real growth (q), which we got by using p. (We can measure x about as well as we can measure anything in macroeconomics). A recession is typically declared if we have two consecutive quarters of negative real growth. Problems In The Calculations. It has been reported than Federal Reserve worries that we have overestimated inflation and consequently underestimated real growth (q). For example, suppose x = 7% for some year, that we measure inflation as p = 3, and from that we calculate real growth as q = 4. But imagine that actually inflation is only 2%: then real growth is actually 5%. It seems quite likely that as the quality of a good improves, the “real” price of the good will be overestimated. As an example, suppose this year’s computer computes 25% faster than last year’s computer and sells for the same price. This actually means that the price of buying computing has fallen -- the same amount of money can buy more of it. But all we see are two machines of the same price. We say that computers got no cheaper this year, even though computing did get cheaper. We have yet to find a way to measure that difference. Increasingly more of our modern economy involves producing goods of ever-improving quality and we have yet to find away to satisfactorily capture that truth in our numbers. Section D. The Product Market Equation. page 2 Macroeconomics, Kvaran B. THE EFFECTS OF SPENDING CHANGES. (Changes of demand in the product market) What happens when Demand changes. What is the effect of a change of spending? An increase in nominal spending (x) will produce some combination of real growth (q) and inflation (p) that add up to the percent change of spending. If spending rises by 10% in a given year, then some of the possible outcomes are given in the table. A 10% increase of spending could cause -inflation real of: growth of: 1% 9% a little inflation, a lot of real growth. 9% 1% a lot of inflation, a little real growth … or any number of other possibilities. Which outcome actually occurs will depend on a variety of factors facing producers and sellers, such as: • what are the costs of producing additional production. o are inventories available, or must you produce new output o do you have idle equipment and workers o is it easy to find additional supplies and to hire additional workers • are you expected to increase output for a long time or only a short time. • how much competition there is. For a given x, we would expect growth (q) to be large and inflation (p) to be small if: • the costs of production additional output are high/low • increased demand will be met with existing inventories/new output • additional supplies and workers are cheap and easy/difficult and expensive to find • producers have/do not have idle equipment. • the economy is in a recession/boom • the time under consideration is a long/short time. • there is/is not a lot of competition (foreign competition, for example) For our purposes, the two most important variables are (a) the length of time involved, and (b) how the economy is doing when spending changes. a. the passage of time: the shorter the amount of time involved, the greater the impact on output (q). As more time passes, it is more likely that we will get more inflation and less real growth. That is, when faced with an increase in spending (demand) an economy’s first reaction is to produce more goods. It takes some time for the inflationary effects to assert themselves. An economy can produce bursts of increased output that may not be sustainable over time. Section D. The Product Market Equation. page 3 Macroeconomics, Kvaran more in the short run x=p+q more in the long run b. how full employment is. The further an economy is from full employment, the more likely it is that spending increases will cause output growth, rather than inflation. Near full employment, spending is more likely to cause inflation. This is because, as the economy approaches full employment, the costs of generating additional output tend to rise as it becomes more difficult to get additional inputs, and production costs get pushed up. more with high unemployment x=p+q more with low unemployment c. how much competition there is. Competition, domestic or foreign, tends to limit price increases. more with a lot of competition x=p+q more with little competition C. THE EFFECTS OF CHANGES OF COST AND TECHNOLOGY. What happens when Supply changes. We can consider two types of supply changes. 1. changes of technology. This seems to have been an important factor in the growth of the 1990s. 2. changes of costs of production. This seems to describe the effects of the oil price increases of the 1970s. 1. An improvement of technology can be thought of as an increase of real growth (q). For a given x, we would expect a decrease of inflation (p). 2. An increase of the cost of production could be seen as an increase of inflation (p). For a given x this would cause a decrease of real growth. D. SUMMARY of the Product Market Equation Results. 1. x↑ ⇒ p↑ and q↑. This shows the effect of an increase of demand. 2. Improved technology ⇒ q↑ and p↓. 3. Increased production costs ⇒ q↓ and p↑. Section D. The Product Market Equation. page 4 Macroeconomics, Kvaran E. A BIT OF HISTORY by the Decades Decade 1930s 1940s 1950s 1960s the Depression World War II 1970s early 1980s later 1980s 1991 1990s 2000 the Democrat era expansion #2 oil price increases the Volcker recession Reagan expansion expansion #3 Desert Storm recession tech expansion (?) expansion #1 Recession Real Growth Unemployment Inflation really high really low low -price controls high low rising low low high high high falling high falling low high low low low rising falling We would expect real growth and unemployment to be opposites. 9.0 AVERAGES 8.0 q 7.0 p U 6.0 5.0 4.0 3.0 2.0 1.0 0.0 1960s 1960s 1970s 80 - 83 84 - 89 1990s 2000s All 1970s Averages q p U 4.3 2.5 4.8 3.3 6.6 6.2 1.8 6.5 8.5 3.8 3.1 6.9 3.2 2.2 5.8 2.5 2.0 5.2 3.3 3.7 5.9 80 - 83 q -5.2 -4.8 -8.1 1.0 -3.0 -1.4 -8.1 Min p 0.4 2.3 2.9 1.0 0.8 1.1 0.4 84 - 89 U 3.4 4.2 6.3 5.2 4.1 3.9 3.4 1990s 2000s Max COMMENTS q p U 9.8 5.8 7.0 A walk up the Phillips Curve 15.8 12.4 8.9 Oil Prices rise twice 9.0 11.2 10.7 The Volcker recession ends inflation 7.8 7.8 7.9 The Reagan expansion 7.1 4.8 7.6 Technology triumphs (?) 7.2 3.3 6.1 15.8 12.4 10.7 Section D. The Product Market Equation. page 5 Macroeconomics, Kvaran F. GRAPHING the product market equation 1. Equilibrium 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 %p D %q D 0 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 The Demand line shows all the combinations of growth and inflation that add up to 10% -what buyers are willing to spend. The Supply line then determines which combination will be offered. In this case we get: growth of 4% inflation of 6% S p 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 2. Demand Changes p% Suppose there is an increase of demand. Buyers are now willing to spend x = 12% instead of the previous x = 10%. Price and quantity both increase. S In this case we get: growth rises from 4% to 4.8% inflation rises from 6% to 7.2% D2 D1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 q% 10 11 12 3. Supply Changes 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 %p S1 S2 Suppose costs of production decrease, perhaps because of improved technology. This is shown by an increase of supply. In this case inflation decreases (6% to 4.8%) and growth speeds up (from 4% to 5.2%). D 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 %q 10 11 12 Section D. The Product Market Equation. page 6 Macroeconomics, Kvaran