* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Decoding the Secrets of Eqyptian Hieroglyphs

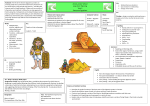

Middle Kingdom of Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Index of Egypt-related articles wikipedia , lookup

Prehistoric Egypt wikipedia , lookup

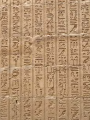

Rosetta Stone wikipedia , lookup

Military of ancient Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Egyptian race controversy wikipedia , lookup

Egyptian language wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Egyptian technology wikipedia , lookup