* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download CLoSA Draft Chapter 34 Limitations

United Arab Emirates Legal Process wikipedia , lookup

Purposive approach wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional Court of Thailand wikipedia , lookup

Scepticism in law wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional Council (France) wikipedia , lookup

Polish Constitutional Court crisis, 2015 wikipedia , lookup

Criminalization wikipedia , lookup

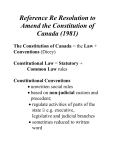

Section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms wikipedia , lookup