* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Axiom Sets

History of geometry wikipedia , lookup

Multilateration wikipedia , lookup

Projective plane wikipedia , lookup

Lie sphere geometry wikipedia , lookup

Perspective (graphical) wikipedia , lookup

History of trigonometry wikipedia , lookup

Contour line wikipedia , lookup

Duality (projective geometry) wikipedia , lookup

Euler angles wikipedia , lookup

Integer triangle wikipedia , lookup

Pythagorean theorem wikipedia , lookup

Trigonometric functions wikipedia , lookup

Compass-and-straightedge construction wikipedia , lookup

Rational trigonometry wikipedia , lookup

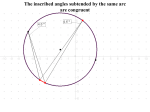

Geometry: Sets of Eclidean Axioms MATH 3120, Spring 2016 1 Euclid’s Postulates The works of Euclid are not rigorous in the modern sense. His results rely upon unstated assumptions. His set of axioms was not complete - we need to add a few to guarantee that what we think of Euclidean geometry actually turns up. He did not realize the need for undefined terms, and for this reason his actual definitions rely upon “common understanding.” However, Euclid’s Elements served as the world’s geometry textbook for more than 2,000 years. We will approach Euclide from the modern perspective. We will look first at the axioms. Though he began with definitions, we will postpone them until later and focus instead on the postulates and propositions. Note that Euclid’s 5th postulate is the famous (or infamous) “parallel postulate.” Euclid’s postulates are as follows: 1. To draw a straight line from any point to any point. 2. To produce a finite straight line continuously in a straight line. 3. To describe a circle with any center and radius. 4. That all right angles equal one another. 5. That, if a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which are the angles less than the two right angles. Euclid offers the following common notions: 1. Things which equal the same thing also equal one another. 2. If equals are added to equals, then the wholes are equal. 3. If equals are subtracted from equals, then the remainders are equal. 4. Things which coincide with one another equal one another. 5. The whole is greater than the part. Here we will return to definitions. You will see that several of these should be undefined terms, and the rest should be based upon the undefined terms and axioms. These definitons do try to describe Euclidean figures. Modern geometers take the spirit of Euclid and “patch up” his axiomatics to make things work as intended. 1. A point is that which has no part. 2. A line is breadthless length. 3. The ends of a line are points. 4. A straight line is a line which lies evenly with the points on itself. 5. A surface is that which has length and breadth only. 6. The edges of a surface are lines. 7. A plane surface is a surface which lies evenly with the straight lines on itself. 1 8. A plane angle is the inclination to one another of two lines in a plane which meet one another and do not lie in a straight line. 9. And when the lines containing the angle are straight, the angle is called rectilinear. 10. When a straight line standing on a straight line makes the adjacent angles equal to one another, each of the equal angles is right, and the straight line standing on the other is called a perpendicular to that on which it stands. 11. An obtuse angle is an angle greater than a right angle. 12. An acute angle is an angle less than a right angle. 13. A boundary is that which is an extremity of anything. 14. A figure is that which is contained by any boundary or boundaries. 15. A circle is a plane figure contained by one line such that all the straight lines falling upon it from one point among those lying within the figure equal one another. 16. And the point is called the center of the circle. 17. A diameter of the circle is any straight line drawn through the center and terminated in both directions by the circumference of the circle, and such a straight line also bisects the circle. 18. A semicircle is the figure contained by the diameter and the circumference cut off by it. And the center of the semicircle is the same as that of the circle. 19. Rectilinear figures are those which are contained by straight lines, trilateral figures being those contained by three, quadrilateral those contained by four, and multilateral those contained by more than four straight lines. 20. Of trilateral figures, an equilateral triangle is that which has its three sides equal, an isosceles triangle that which has two of its sides alone equal, and a scalene triangle that which has its three sides unequal. 21. Further, of trilateral figures, a right-angled triangle is that which has a right angle, an obtuseangled triangle that which has an obtuse angle, and an acute-angled triangle that which has its three angles acute. 22. Of quadrilateral figures, a square is that which is both equilateral and right-angled; an oblong that which is right-angled but not equilateral; a rhombus that which is equilateral but not rightangled; and a rhomboid that which has its opposite sides and angles equal to one another but is neither equilateral nor right-angled. And let quadrilaterals other than these be called trapezia. 23. Parallel straight lines are straight lines which, being in the same plane and being produced indefinitely in both directions, do not meet one another in either direction. Finally, we get to Euclid’s theorems. He called them propositions. More exist than are listed here. However, the most important thing to notice is that Euclid didn’t use his controversial 5th postulate until Proposition 27 which is evidence he was concerned about it. Other Greek mathematicians criticised the 5th postulate, thinking it was a theorem (proposition) that could be proven. While they were all correct to be concerned, they failed to see through to the heart of the matter. Here are Euclid’s first 32 postulates: 1. To construct an equilateral triangle on a given finite straight line. 2. To place a straight line equal to a given straight line with one end at a given point. 3. To cut off from the greater of two given unequal straight lines a straight line equal to the less. 2 4. SAS Congruence Condition. If two triangles have two sides equal to two sides respectively, and have the angles contained by the equal straight lines equal, then they also have the base equal to the base, the triangle equals the triangle, and the remaining angles equal the remaining angles respectively, namely those opposite the equal sides. 5. In isosceles triangles the angles at the base equal one another, and, if the equal straight lines are produced further, then the angles under the base equal one another. 6. If in a triangle two angles equal one another, then the sides opposite the equal angles also equal one another. 7. Given two straight lines constructed from the ends of a straight line and meeting in a point, there cannot be constructed from the ends of the same straight line, and on the same side of it, two other straight lines meeting in another point and equal to the former two respectively, namely each equal to that from the same end. 8. If two triangles have the two sides equal to two sides respectively, and also have the base equal to the base, then they also have the angles equal which are contained by the equal straight lines. 9. To bisect a given rectilinear angle. 10. To bisect a given finite straight line. 11. To draw a straight line at right angles to a given straight line from a given point on it. 12. To draw a straight line perpendicular to a given infinite straight line from a given point not on it. 13. If a straight line stands on a straight line, then it makes either two right angles or angles whose sum equals two right angles. 14. If with any straight line, and at a point on it, two straight lines not lying on the same side make the sum of the adjacent angles equal to two right angles, then the two straight lines are in a straight line with one another. 15. If two straight lines cut one another, then they make the vertical angles equal to one another. Corollary. If two straight lines cut one another, then they will make the angles at the point of section equal to four right angles. 16. In any triangle, if one of the sides is produced, then the exterior angle is greater than either of the interior and opposite angles. 17. In any triangle the sum of any two angles is less than two right angles. 18. In any triangle the angle opposite the greater side is greater. 19. In any triangle the side opposite the greater angle is greater. 20. In any triangle the sum of any two sides is greater than the remaining one. 21. If from the ends of one of the sides of a triangle two straight lines are constructed meeting within the triangle, then the sum of the straight lines so constructed is less than the sum of the remaining two sides of the triangle, but the constructed straight lines contain a greater angle than the angle contained by the remaining two sides. 22. To construct a triangle out of three straight lines which equal three given straight lines: thus it is necessary that the sum of any two of the straight lines should be greater than the remaining one. 3 23. To construct a rectilinear angle equal to a given rectilinear angle on a given straight line and at a point on it. 24. If two triangles have two sides equal to two sides respectively, but have one of the angles contained by the equal straight lines greater than the other, then they also have the base greater than the base. 25. If two triangles have two sides equal to two sides respectively, but have the base greater than the base, then they also have the one of the angles contained by the equal straight lines greater than the other. 26. If two triangles have two angles equal to two angles respectively, and one side equal to one side, namely, either the side adjoining the equal angles, or that opposite one of the equal angles, then the remaining sides equal the remaining sides and the remaining angle equals the remaining angle. 27. If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the alternate angles equal to one another, then the straight lines are parallel to one another. 28. If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the exterior angle equal to the interior and opposite angle on the same side, or the sum of the interior angles on the same side equal to two right angles, then the straight lines are parallel to one another. 29. A straight line falling on parallel straight lines makes the alternate angles equal to one another, the exterior angle equal to the interior and opposite angle, and the sum of the interior angles on the same side equal to two right angles. 30. Straight lines parallel to the same straight line are also parallel to one another. 31. To draw a straight line through a given point parallel to a given straight line. 32. In any triangle, if one of the sides is produced, then the exterior angle equals the sum of the two interior and opposite angles, and the sum of the three interior angles of the triangle equals two right angles. 4 2 Hilbert’s Axioms The system begins with undefined terms point, line and plane and the fundamental incidence relation. We need two more relations: the betweenness relation denoted by *, and the congruence relation denoted by ∼ =. All three relations are undefined and are given meaning within the corresponding set axioms. In addition, we need a continuity axiom to ensure circles and lines intersect as they should, and, of course, some axiom about parrallels. A quick note about incidence: although the relation P ∈ l should, strictly speaking, be read: “P and l are incident,” we shall use “l contains P ,” “P lies on l” or any obviously equivalent such expression. 2.1 Incidence Axioms I.1 For every pair of distinct points A and B there is a unique line l containing A and B. I.2 Every line contains at least two points. I.3 There are at least three points that do not lie on the same line. 2.2 Betweenness Axioms The next group of axioms deals with the relation “B lies between A and C.” We will use the notation A ∗ B ∗ C for “B lies between A and C.” B.1 If A ∗ B ∗ C, then A, B and C are distinct points on a line, and C ∗ B ∗ A also holds. B.2 Given two distinct points A and B, there exists a point C such that A ∗ B ∗ C. B.3 If A, B and C are distinct points on a line, then one and only one of the relations A ∗ B ∗ C, B ∗ C ∗ A and C ∗ A ∗ B is satisfied. B.4 Let A, B and C be points not on the same line and let l be a line which contains none of them. If D ∈ l and A ∗ D ∗ B, there exists an E on l such that B ∗ E ∗ C, or an F on l such that A ∗ F ∗ C, but not both. If we think of A, B and C as the vertices of a triangle, another formulation of B4 is this: If a line l goes through a side of a triangle but none of its vertices, then it also goes through exactly one of the other sides. This formulation is also called Paschs Axiom. Note that this is not true in Rn where n ≥ 3. Hence, I.3 and B.4 together define the geometry as “2-dimensional.” 2.3 Congruence Axioms We have two sets of congruence axioms. The first set describes congruent line segments. C.1 Given a segment AB and a ray r from C, there is a uniquely determined point D on r such that CD ∼ = AB. C.2 ∼ = is an equivalence relation on the set of segments. C.3 If A ∗ B ∗ C and A0 ∗ B 0 ∗ C 0 and both AB ∼ = A0 B 0 and BC ∼ = B 0 C 0 , then also AC ∼ = A0 C 0 . The second set describes angle congruence. −−→ C.4 Given a ray AB and an angle ∠B 0 A0 C 0 , there are angles ∠BAE and ∠BAF on opposite sides of −−→ ∼ ∠BAF ∼ AB such that ∠BAE = = ∠B 0 A0 C 0 . 5 C.5 ∼ = is an equivalence relation on the set of angles. C.6 Given triangles 4ABC and 4A0 B 0 C 0 . If AB ∼ = A0 B 0 , AC ∼ = A0 C 0 and ∠BAC ∼ = ∠B 0 A0 C 0 , then 0 0 0 0 0 ∼ ∼ ∼ the two triangles are congruent: BC = B C , ∠ABC = ∠A B C and ∠BCA = ∠B 0 C 0 A0 . 6 3 Birkhoff ’s Axioms Birkhoff’s Axiom set is an example of what is called a metric geometry. A metric geometry has axioms for distance and angle measure which leverage the properties of real numbers and the real number line. Birkhoff used the following undefined terms: • Points • Sets of points called lines • Distance between any two points A and B: a non-negative real number d(A, B) such that d(A, B) = d(B, A) • Angle formed by three ordered points A, O, B (A 6= O, B 6= O): ∠AOB a real number (mod 2π). The point O is called the vertex of the angle. Birkhoff used only four axioms: 1. Line Measure Axiom. The points A, B, . . . of any line l can be placed into one-to-one correspondence with the real numbers x so that |xA − xB | = d(A, B) for all points A, B. 2. Point-Line Axiom. One and only one line l contains two given points P , Q (P 6= Q). 3. Angle Measure Axiom. The half-lines l, m, . . . through any point O can be placed into oneto-one correspondence with the real numbers a(mod2π) so that if A 6= O and B 6= O are points of l and m, respectively, the difference (am − an )(mod2π) is ∠AOB. 4. Similarity Axiom. If in two triangles 4ABC, 4A0 B 0 C 0 and for some constant k > 0, d(A0 , B 0 ) = kd(A, B), d(A0 , C 0 ) = kd(A, C), and m∠B 0 A0 C 0 = ±∠BAC, then also d(B 0 , C 0 ) = kd(B, C), m∠A0 B 0 C 0 = ±∠ABC, and ∠A0 C 0 B 0 = ±∠ACB. Birkhoff provided several defined terms: 1. A point B is between A and C (A 6= C), if d(A, B) + d(B, C) = d(A, C). 2. The points A and C, together with all points B between A and C, form line segment AC. 3. The half-line l0 with endpoint O is defined by two points O, A in line l (A 6= O) as the set of all points A0 of l such that O is not between A and A0 . 4. If two distinct lines have no point in common, they are parallel. A line is always regarded as parallel to itself. 5. Two half-lines through O are said to form a straight angle if m∠mOn = ±π. Two half-lines through O are said to form a right angle if m∠mOn = ± π2 , in which case we also say that m is perpendicular to n. 6. If A, B, C are three distinct points, the segments AB, BC, CA are said to form a triangle 4ABC with sides AB, BC, CA and vertices A, B, C. If A, B, C are collinear, then 4ABC is said to be degenerate. 7. Any two geometric figures are similar if there exists a one-to-one correspondence between the points of the two figures such that all corresponding distances are in proportion and corresponding angles have equal mesure (except, perhaps, for their sign). Any two geometric figures are congruent if they are similar with a constant of proportionality k = 1. 7 4 SMSG Axioms The School Mathematics Study Group was formed during the 1950’s space race to help provide rigor to the geometry instruction in US high schools. This set of axioms is dependent which means that some axioms could be stated as theorems and proven from the other axioms. However, adding extra axioms provides all the tools we need to begin geometry instruction at a reasonable level. For instance, in Hilbert’s or Birkhoff’s axiomatic systems, we have to prove circles exist and then derive their properties. In the SMSG set, we are given the definitions and basic properties as axioms. The undefined terms are point, line and plane. 1. Line Uniqueness. Given any two different points, there is exactly one line which contains both of them. 2. Distance Postulate. To every pair of different points there corresponds a unique positive number. 3. Ruler Postulate The points of a line can be placed in correspondence with the real numbers in such a way that: (a) To every point of the line there corresponds exactly one real number, (b) to every real number there corresponds exactly one point of the line, and (c) The distance between two points is the absolute value of the difference of the corresponding coordinates. 4. Ruler Placement Postulate. Given any two points P and Q on a line, the coordinate system can be chosen in such a way that the coordinate of P is zero and the corrdinate of Q is positive. 5. Points Exist. (a) Every plane contains at least three non-collinear points. (b) Space contains at least four non-coplanar points. 6. Points. If two points lie in a plane, then the whole of the line containing these points lies in the same plane. 7. Plane Uniqueness. There is at least one plane containing any three points, and exactly one plane containing any three non-collinear points. 8. Plane Intersection. If two different planes intersect, then their intersection is a line. 9. Plane Separation Postulate. Given a line and a plane containing it, the points of the plane that do not lie on the line form two sets such that (a) each of the sets is convex, and (b) if P is in one set and Q is in the other, then the segment P Q intersects the line. 10. Space Separation Postulate. The points of space that do not lie in a given plane form two sets such that (a) each of the sets is convex, and (b) if P is in one set and Q is in the other, then the segment P Q intersects the plane. 11. Angle Measurement Postulate. To every angle there corresponds a real number between 0◦ and 180◦ . −−→ 12. Angle Construction Postulate. Let AB be a ray on the edge of the half-plane H. For every −→ r between 0 and 180 there is exactly one ray AP with P in H such that m∠P AB = r. 8 13. Angle Addition Postulate. If D is a point in the interior of m∠BAC, then m∠BAC = m∠BAD + m∠DAC. 14. Supplementary Postulate. If two angles form a linear pair, then they are supplementary. 15. Side Angle Side Postulate. Given a one-to-one correspondence between two triangles (or between a triangle and itself), if two sides and the included angle of the first triangle are congruent to the corresponding parts of the second triangle, the correspondence is a congruence. 16. Parallel Postulate. Through a given external point there is at most one line parallel to a given line. 17. To every polygonal region there corresponds a unique positive real number called its area. 18. If two triangles are congruent, then the triangular regions have the same area. 19. Suppose that the region R is the union of two regions R1 and R2 . If R1 and R2 intersect in at most a finite number of segments and points, then the area of R is the sum of the areas of R1 and R2 . 20. The area of a rectangle is the product of the length of its base and the length of its altitude. 21. The volume of a rectangular parallelepiped is equal to the product of the length of its altitude and the area of the base. 22. Cavalieri’s Principle. Given two solids and a plane, if for every plane that intersects the solids and is parallel to the given plane the two intersections determine regions that have the same area, then the two solids have the same volume. 9