* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Equation Editor and the Equation Field: Go Figure

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

of what you’ll find on each menu. The second button from the left on

the second row, for example, shows choices for building a fraction and

for adding a square root sign. Pull down the menu, and you’ll find

several variations on these basics.

Copyright © 1995-96, Pinecliffe International. All rights

reserved. Woody’s Underground Office™ is a trademark of

Pinecliffe International. Truth by the Gleaming, Merciless

Truckload™ is a trademark of PRIME Consulting Group, Inc.

Windows® is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation.

Pinecliffe International reserves the right to use and modify

reader submissions in any manner, including the right for this

publication’s readers to use such material for any purpose

whatsoever, with the exception that the use of any republished

material with a prior copyright preserve that copyright. No

republication without permission.

This article appeared in WUON Volume 1, Issue 11

(TXDWLRQ(GLWRUDQGWKH

(TXDWLRQ)LHOG*R)LJXUH

by M. David Stone

Most of the features in Microsoft Word fall into one of three

categories. There are some that almost everyone needs just about every

day (like the spelling checker); some that most people need at least

occasionally (like mail merge); and some that most people never use,

but others need so desperately that they’d be lost without them.

High on the list for category three is Microsoft Equation Editor,

Microsoft Office’s mini-application for creating equations as objects.

But don’t stop reading just because you use the Equation Editor every

day and know it backwards and forwards. Because most of what I’m

going to talk about here is how to write equations without Equation

Editor — at least, when you’re using Word. More important, I’m

going to talk about why you might want to ignore Equation Editor,

and when. (Once again, at least when you’re using Word. Equation

Editor, of course, is an OLE server application, which means you can

use it with any OLE client — or container if you insist on

technOLEbabble. The alternative I’ll cover here — Word’s equation

field — is strictly a Word feature.)

For those who aren’t already familiar with Equation Editor,

here’s a quick overview first.

To insert an equation object, you choose Insert / Object, highlight

Microsoft Equation 2.0 in the Object Type list and choose OK.

Windows, through the magic of OLE 2, will insert a blank equation

object in your document, replace your Word menu and toolbar with

the Equation Editor menu, and add an equation toolbar to your screen.

The toolbar, shown in Figure 1, consists of unnamed pull-down

menus with menu buttons (for lack of a better term) that show samples

Figure 1: The Equation Editor Toolbar

The choices on this and other menus insert templates in the

equation. The dotted boxes indicate places where you can enter text —

both the numerator and denominator of the fraction, for example.

Other toolbar menus — including the five rightmost buttons on the top

row — offer common mathematical symbols. To create an equation,

you pick and choose from the menus to insert templates and symbols

as needed, and you type text where possible. Most important, you see

the equation as you work with it.

THE EQUATION FIELD, A LITTLE-KNOWN SECRET

Equation Editor isn’t the only way to build equations in Word.

Before there was Equation Editor (we’re talking Word 1.x here), there

was the equation field. This takes the form:

{EQ equation}

More to the point, even with Equation Editor long since

available, there is still the equation field. (Don’t confuse this with the

formula field. The formula field calculates an answer to a formula. The

equation field lets you create an equation as part of your document.)

You can enter the equation field just like any other field. One

choice is to use the Insert / Field command. However, if you can

remember the name of the field without having to see it on a list (EQ

for equation shouldn’t tax your memory too much), or you think

menus are for weenies, you’ll probably find it a lot easier to simply

type the field. Position the cursor where you want the equation and

press Ctrl+F9. Word will enter the start and end markers — which

look like bolded curly braces. You can then type the text for the field

between the markers, and, with the cursor still in the field, hit F9 to

update it.

One warning: If Word is in overtype mode when you’re entering

or editing a field, you won’t be able to add text that would increase the

number of characters inside the markers. If your computer dings with

each keystroke and nothing happens on the screen, make sure you’re

in insert mode and try again.

Note too that regardless of how you enter the field in the first

place — by menu or by function key command — you can edit the

field code at any time. Alt+F9 will toggle Word between showing the

field code and field result. Set Word to show the field codes, make the

changes you need, then hit F9 to update the field and Alt+F9 again to

toggle back to field results.

1

The equation field itself can’t do everything that Equation Editor

can do. For example, you won’t find codes for entering the

mathematical symbols on Equation Editor’s menus. But you can

combine the field with appropriate fonts to get all the mathematical

symbols you need. And the equations look pretty much the same.

Figure 2 shows some text along with three equations (the first being

the word test surrounded by a box) created with Equation Editor.

{eq x = x\s\do2(0) \r(,1 - \f(v\s(2),c\s(2)))}

If you can’t immediately see the connection between these codes

and the actual equations, you’re not alone. And keep in mind that

these equations are relatively simple. Try to build a complex equation,

and you’ll quickly get lost in the maze of switches, nested parentheses,

and an unhelpful, bold Error! for the field result if you make a

mistake. This is a far cry from Equation Editor’s approach, with pulldown menus and onscreen formatting.

And now you know why Equation Editor is the recommended

choice for building equations while the equation field is a forgotten

backwater.

WHAT’S RIGHT WITH THE EQUATION FIELD

Figure 2: Inline Equation Editor Using Equation Objects

Figure 3, which differs only in subtle ways, shows the same text,

but equations created by the equation field.

Figure 3: The Same Inline Equation via Equation Fields

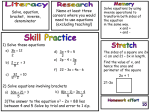

WHAT’S WRONG WITH THE EQUATION FIELD

The problem with the equation field is that you have to use an

arcane set of codes, or switches. And working with those codes is

clumsy. How arcane? How clumsy?

Well, suppose you want to create the word test with a box around

it, as in the figures. The equation field uses the switch \x() to add a box

to whatever you put in the parentheses. So the field in this particular

case would be:

{Eq \x(test)}

That’s not bad. But what about the second and third equations in

the figures — the ones with fractions, square roots, subscripts, and

superscripts? (The equations, by the way, are from special relativity,

which may be easier to work with than the equation field.)

I won’t go into details here. Word’s help screens (which I’ll talk

about shortly) do a good job of that already. But if you mix the

switches together the right way — \f(,) for fractions, \r(,) for the

radical sign, and so forth — and you throw in the right text (with the

superscripts and subscripts formatted to an appropriately small font

size), the first equation comes out to:

{eq t = \f(t\s\do2(0),\r(,1 - \f(v\s(2),c\s(2))))}

So, if the equation field is so complicated, why did I bring it up?

Well, there are times when you may want to use it anyway. Despite its

shortcomings.

If you have a minimal installation, for example, and you’ve left

out Equation Editor, the equation field is your only choice. And note

that when you move the file to a system that has Equation Editor

installed, you can convert the EQ field equations to Equation Editor

objects by double-clicking on them. Be careful about that, though.

Once you’ve converted an equation object, there’s no way to convert it

back to a field.

Another plus for the equation field is that it makes for smaller

files. The file that I used for Figure 3, with three lines of text and three

equations created with the equation field, is just 11,264 bytes — the

same length as an identical text file minus the fields. The file I used for

Figure 2, which uses Equation Editor objects instead of fields, is

17,920 bytes. The more equations you use, the more of a difference

you’ll see.

Be aware that Word’s help system makes it easy to keep the list

of equation field switches handy while you’re building an equation.

Choose Help / Microsoft Word Help Topics, go to the Find card and

enter Equation as the word you want to find. Then choose Field

Codes: Eq (Equation) field as the topic you want to display.

Word will show you a shorthand description of each switch in a

window that you can move to the side of the screen and refer to as you

work in the document. If you need more details, you can click on the

small double arrow icon to the right of each switch description. Then

you can return to the full list of shorthand descriptions with the Back

button. In between working on equations, you can minimize the

window and leave the icon on the Taskbar, so you can bring it up

again quickly and easily.

Not so incidentally, the help screen suggests using the equation

field for inline equations, meaning equations that fall within a line of

And the second comes out to:

2

text. The implication is that you can’t create inline equations with

Equation Editor. Don’t believe it.

If you insert an equation object in the middle of a text line, the

object will move left and right with the text and obey word-wrap rules

for jumping to the next line as needed. You can even create a box

around the equation, as with the word test in Figures 2 and 3, and have

the box and equation move together. Simply select the equation,

choose Format / Borders and Shading, choose Box in the Presets box,

and choose OK. For this particular effect, however, you may find it

easier to use the equation field with the \x() switch, as I’ve already

mentioned.

Ultimately, you’ll want to keep both approaches to equations

handy in your bag of tricks, picking the one that’s most appropriate to

the task at hand. As a general rule, consider using the equation field

for simple equations to save disk space, and reserve Equation Editor

for equations that are complex enough to truly benefit from being able

to see the equation onscreen as you build it. As you get more and more

comfortable with the equation field, you may well find less and less

need to use Equation Editor.

M. David Stone is a writer and occasional computer consultant.

His latest book is The Underground Guide to Color Printers, published

by Addison-Wesley.

3