* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Summary of the Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia

Survey

Document related concepts

Moral treatment wikipedia , lookup

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Psychological evaluation wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

Parkinson's disease wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Mental status examination wikipedia , lookup

Dementia praecox wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

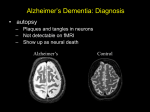

The Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia This article is a summary of the consensus statements formulated by the conference on dementia for the assessment and management of dementia in primary care. by Christopher Patterson, MD, FRCPC A Dr. Christopher Patterson, Professor, Division of Geriatric Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario. s the Canadian population ages, the prevalence of dementia will rise dramatically. There are approximately 270,000 people with dementia currently in Canada; this number is expected to rise to 778,000 by 2031.1 Manifestations of dementing disorders include not only cognitive deficits (which make it difficult to work, drive, manage finances and make decisions) but also behavioral complications (e.g., withdrawn or aggressive behavior, wandering, disinhibition). Family physicians, who provide the majority of care for older people, must be skilled in the diagnosis and management of dementia. A family physician with 1,200 patients may have 12 patients with dementia in their practice. These facts underscore the importance of developing clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for primary care physicians. The Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia (CCCD) used a rigorous process to obtain, select, grade and review evidence. Background papers were prepared and circulated to conference participants, all of whom had expertise in 8 • The Canadian Alzheimer Disease Review • September 1999 dementia or a related area. These papers were discussed and recommendations (consensus statements upon which the CPGs are based) were finalized at a conference in Montreal in February 1998. These recommendations have been published in a supplement to the Canadian Medical Association Journal.2 A “physicians guide” to their use has also been published.3 The recommendations are summarized here, but the reader is encouraged to read the supplement, which summarizes the evidence for these statements. The supplement is also available at www.cma.ca. Types of Dementia Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is by far the most common cause of dementia in Canada, accounting for more than 60% of all cases. Vascular dementia is less common, and people previously thought to have vascular dementia often have co-existent AD. Patients with frontotemporal dementia usually show signs of early behavior problems and language involvement. Dementia with Lewy bodies is characterized by early hallucinations and delusions, extrapyramidal side effects, sensitivity to neuroleptics and a marked day-today fluctuation in confusion. Dementia—A Clinical Diagnosis Although some aspects of cognitive performance deteriorate with age, cognitive losses that lead to declining function in occupational, social or dayto-day functioning are associated with dementia. If mental status testing uncovers objective evidence of memory loss or decline in other areas, the ability to perform daily activities should be assessed. The most important aspect of establishing a diagnosis of dementia is obtaining a thorough history from the patient, and a corroborative history from caregivers. The history should include a description of the onset, course and duration of the problem. Inquiries should be made about previous psychiatric problems (e.g., depression), risk factors (e.g., substance abuse, vascular disease, family history) and neurological symptoms (e.g., new onset headache). A physical examination should include a search for systemic disease, focal neurological signs and a mental status evaluation. The Mini- reversible causes are much less common than previously thought,5 emphasis is now on confirming the diagnosis on the basis of the patient’s history. For example, AD is typified by a gradual, insidious loss of memory, usually followed by difficulties with language, praxis (performing familiar tasks) and visuospatial disturbances such as agnosias (failure to recognize familiar people or surroundings). Behavioral problems usually appear later in the course of the disease. The average duration of the disease from onset to death is about seven years. Tests for patients who display typical cognitive symptoms or presentation include a complete blood count and measurement of thyroid stimulating hormone, serum electrolytes, serum calcium and serum glucose levels. In atypical cases, laboratory tests may be indicated. Neuroimaging, most commonly computed tomography (CT), can detect certain causes of dementia such as vascular dementia, tumor, normal pressure hydrocephalus or subdural hematoma; it is ineffective in distinguishing AD or other cortical dementias from normal Dementia can be detected early if the family physician maintains a high index of suspicion in elderly patients and follows up observations of functional decline and memory loss. Memory complaints should be evaluated. When caregivers report cognitive decline in a patient, cognitive assessment and careful follow-up are indicated. Mental State Examination (MMSE)4 is a good starting point, but other cognitive domains (e.g., insight, judgment) should also be assessed. A review of all prescription and nonprescription medications is essential. This information will often point to a specific diagnosis. Laboratory Tests for All Patients In the past, emphasis has been placed on investigations to rule out “reversible” causes of dementia. Because these aging. CT scans should be restricted to those people who meet the criteria in Table 1. Adhering to these “rules” reduced the number of scans performed in a memory clinic by two thirds.6 Referrals Typical characteristics of AD are insidious onset, progressive decline over seven to 10 years, and a gradual loss of cognitive and functional abilities. Physicians are encouraged to seek help Table 1 CT Scans Are Recommended for Patients • younger than 60 years of age, • who have a rapid unexplained decline in cognition or function (over one to two months), • who have a short duration of dementia (less than two years), • who have had a recent and significant head trauma, unexplained neurologic symptoms (e.g., new onset of severe headache or seizures), • who have a history of cancer (especially in sites and types that metastasize to the brain) use anticoagulants or have a history of a bleeding disorder, • who have a history of urinary incontinence and gait disorder early in the course of dementia (as may be found in normal pressure hydrocephalus), • who have any new localizing sign (e.g., hemiparesis or a Babinski reflex), • who have unusual or atypical cognitive symptoms or presentation (e.g., progressive aphasia), • or have gait disturbance. when patients do not follow this typical pattern (e.g., those who manifest early behavioral changes or delusions, fluctuating course, early motor changes) or when management difficulties arise (Table 2).3 Early Detection Dementia can be detected early if the family physician maintains a high index of suspicion in elderly patients and follows up observations of functional decline and memory loss. Memory complaints should be evaluated. When caregivers report cognitive decline in a patient, cognitive assessment and careful follow-up are indicated. There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend screening with short mental status questionnaires for cognitive impairment in the absence of symptoms or in unselected older people. Genetic Counselling Genetic counselling is recommended when there is a strong family history of The Canadian Alzheimer Disease Review • September 1999 • 9 Figure 1 Diagnosis of Dementia Complaints of memory loss Yes Suspect dementia Caregiver confirms Yes Yes Decline in function Objective evidence of cognitive decline Take history of illness from patient and reliable informant. Include: • onset of symptoms • duration of symptoms • evolution of symptoms • precipitating factors • family history Conduct physical examinations No No Subjective complaints No Dementia excluded as a possible diagnosis. Symptoms may be the result of depression or anxiety. Re-evaluate in 3 to 6 months. Conduct mental and functional assessment (e.g., MMSE and FAQ) Conduct laboratory tests CBC, TSH, electoytes, calcium, glucose Conduct other tests as indicated (CT or MRI in specific cases*) Eliminate presence of reversible conditions: • substance abuse • adverse drug effects • depression • metabolic disorders • systemic illness Yes Treat these causes Are there other causes for the symptoms? No * See table of indications 10 • The Canadian Alzheimer Disease Review • September 1999 Diagnosis of dementia confirmed. Figure 2 Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) Diagnosis of AD Disclose diagnosis to patient and family Provide support and education for caregiver and refer to support organizations Are there contributory or treatable causes of dementia? Yes Treat contributory causes (e.g., hypothyroidism, reduce sedative drugs) No Establish baseline measures MMSE Measure of function (e.g., FAQ) Begin caregiver diary Initiate treatment with donepezil for informed and willing patients with no contraindications Re-assess in 3 months Repeat baseline measures Improvement in measures Yes Continue treatment with donepezil No Reconsider diagnosis and/or treatment and refer to specialist Re-assess regularly The Canadian Alzheimer Disease Review • September 1999 • 11 Alzheimer’s disease, particularly when the onset is below the age of 60. Risk Factors and Prevention of Dementia The risk of dementia may be reduced by effectively treating vascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, smoking, atrial fibrillation).6 Recent evidence suggests that substandard education (less than six years), head trauma, Down syndrome, and family history may increase the risk of AD. This opportunity for prevention has been underused in the past. Although evidence is currently insufficient to recommend estrogen replacement, (NSAIDs) or antioxidants to prevent dementing disorders, this is an area of active research. Some authorities encourage the use of vitamin E, because it is relatively harmless, inexpensive and may be beneficial. accurately defines driving risk. Although the risk of crashes increase as dementia progresses, there is no definite age or MMSE score before which driving can be confidently assumed to be safe. Sedative drugs increase the risk of crashes.8 Caregiver Issues Solid partnerships between primary care physicians and caregivers help families cope with their role. Caregivers are in a position to monitor status and symptoms and should be included in treatment planning. Physicians can help caregivers by acknowledging the value of their work, educating them about the disease and helping them deal with stress. Support for caregivers is the most important aspect of managing a demented person. Various strategies and support organizations can greatly Physicians can help caregivers by acknowledging the value of their work, educating them about the disease and helping them deal with stress. Support for caregivers is the most important aspect of managing a demented person. Ethical Issues The wide scope of ethical issues such as participation in research, decision making, respecting individuals’ decisions, quality of life, behavior control, use of restraints, advance directives and end-of-life decisions have been dealt with elsewhere.7 The CCCD recommendations deal with only two specific issues: disclosure and driving. Ethical analysis concludes that, in general, diagnosis should be disclosed to people with dementia. Disclosure allows the patient to set out advance directives and make end-of-life decisions.7 Office assessment of driving ability is notoriously inaccurate. When in doubt, a performance-based assessment (including an on-road test) more help the caregiver. A program of education, case management and support for the caregiver from the Alzheimer Society has been shown to delay a patient’s admission to a long-term care institution by approximately one year.9 Support programs can also provide caregivers with information about legal and financial issues. Cultural Aspects In some cultures the concept of dementia does not exist. Conventional mental status tests frequently overestimate the cognitive deficits of people from different linguistic and cultural groups. It is important to provide services that are culturally appropriate. 12 • The Canadian Alzheimer Disease Review • September 1999 Table 2 Refer Patients to Other Health Care Professionals • if diagnosis is uncertain after the initial assessment and follow-up, • if the patient or his or her family want a second opinion, • in the presence of significant depression (especially if there is no response to treatment, treatment problems or failure with new medications for AD), • if the need arises for additional help in patient management (e.g., behavioral problems) or caregiver support, • when genetic counselling is indicated, • when research studies into diagnosis or treatment are being carried out. Depression and Dementia Depression is extremely common in early stages of AD. Physicians should consider a diagnosis of depression when patients experience behavioral symptoms, weight and sleep changes, sadness, crying, suicidal statements or excessive guilt. Nonpharmacologic therapy should be initiated if depressive symptoms are not part of a major affective disorder, severe dysthymia or severe emotional lability. Medication should be considered for more severe depression. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibiors (SSRIs) and reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMA) antidepressants are generally preferred over tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), which have anticholinergic effects that can aggravate cognitive deficits.10 Individuals with AD are particularly sensitive to anticholinergic agents. Referral to a specialist may be necessary if the depression is atypical or refractory. Behavioral Problems Behavioral difficulties are common and are often the most challenging complications of a dementing illness. It is important to evaluate causes and to document behavior carefully before resorting to pharmacologic treatment.11 Environmental modifications (changes to sound, light, people) are often effective. The value of neuroleptic drugs has been overestimated in the past, and in general, a cautious approach is recommended, using low doses, cautious escalation and careful observation. The newer atypical neuroleptics may offer advantages over traditional agents.12 If symptoms are successfully controlled with pharmacotherapy, physicians should regularly evaluate the need for continuing treatment and reduce or withdraw the drugs if possible. Pharmacologic Management of Dementia The goal of therapy is to halt or slow cognitive and functional decline, improve memory and other cognitive functions, maintain or improve the ability to perform daily activities, improve behavioral abnormalities, and improve mood, contentedness and quality of life of the patient, which will also improve the quality of life of the caregiver. None of the drugs that are currently available meet all of these criteria, but symptomatic treatment is available. Donepezil is currently the only medication approved by Health Canada to treat mild to moderate AD.13,14 Baseline References 1. Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group: Canadian study of health and aging: study methods and prevalence of dementia. CMAJ 1994; 150:899-913. 2. Patterson CJS, Gauthier S, Bergman H, et al.: The recognititon and management of dementing disorders: conclusions from the Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia. CMAJ 1999;160 (Suppl 12). 3. Patterson CJS, Gauthier S, Bergman H, et al.: Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia: a physicians' guide to using the recommendations. CMAJ 1999; 160:1738-42. 4. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini Mental State”: a practical method of grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatry Res 1975; 12:189-98. 5. Clarfield AM: The reversible assessments should be made before prescribing donepezil, and serial examinations should be conducted to determine whether the medication is effective. In addition to the physician’s assessment (which should include cognitive (e.g., MMSE4) and functional measures (e.g., functional assessment questionnaire15)) caregivers of the affected individual should be encouraged to record their observations in a daily diary and should be given realistic expectations. There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend vitamin E or Ginkgo biloba therapy for patients with AD. support of the Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia: Bayer Healthcare Division; Boehringer Ingelheim Canada Ltd.; Hoechst Marion Roussel; Janssen-Ortho Pharmaceutical Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc; Pfizer Canada Inc.; SmithKline Beecham Pharma; Consortium of Canadian Centres for Clinical Cognitive Research; Division of Geriatric Medicine, McMaster University; Division of Geriatric Medicine, McGill University; McGill Centre for Studies in Aging. Endorsement Conclusions The conference organizers would like to express their appreciation to the following organizations for providing grants in The following organizations endorsed consensus recommendations: Alzheimer Society of Canada; Canadian Academy of Geriatric Psychiatry; Canadian Society of Geriatric Medicine; College of Family Physicians of Canada; Consortium of Canadian Centres for Clinical Cognitive Research (C5R); Canadian Neurological Society; and the Société québécoise de gériatrie. Members of the steering committee included: Drs. C. Patterson, S. Gauthier, H. Bergman, C. Cohen, J. Feightner, H. Feldman, A. Grek, and D. Hogan. dementias: do they reverse? Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:476-86. 6. Freter S, Bergman H, Gold S, et al.: Prevalence of potentially reversible dementias and actual reversibility in a memory clinic cohort. CMAJ 1998; 159:657-62. 7. Tough issues: ethical guidelines. Toronto: Alzheimer Society of Canada, 1997. 8. Hemmelgarn B, Suisa S, Huang A, et al.: Benzodiazepine use and risk of motor vehicle crashes. JAMA 1997; 278:27-31. 9. Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, et al.: A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer's disease. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1996; 276:725-31. 10. Wragg RE, Jeste DV: Overview of depression in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 145:577-87. 11. Beck CK, Shue VM: Interventions for treating disruptive behavior in demented elderly people. Nurs Clin North Am 1994; 29:143-55. 12. Katz IR, Jeste DV, Mintzer JE, et al.: Comparison of risperidone and placebo for psychosis and behavioral disturbances associated with dementia—a randomized, double-blind trial. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:107-15. 13. Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT, the Donepezil Study Group. The efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: results of a US multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dementia 1996; 7:293-303. 14. Rogers SL, Farlow MR, Doody RS, et al.: A 24-week, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1998; 50:136-45. 15. Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH: Measurement of functional activities of older adults in the community. J Gerontol 1982; 37:323-9. The foregoing is a brief summary of the consensus statements formulated by the Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia for the assessment and management of dementia in primary care. This should be used only as a guide; the reader is urged to review the full recommendations published in CMAJ2 and the “physicians guide” to their use.3 Funding Support The Canadian Alzheimer Disease Review • September 1999 • 13