* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Curriculum and Assessment 3-11 E

Stress and vowel reduction in English wikipedia , lookup

Philippine English wikipedia , lookup

American and British English spelling differences wikipedia , lookup

English-language vowel changes before historic /r/ wikipedia , lookup

Ugandan English wikipedia , lookup

English phonology wikipedia , lookup

History of English wikipedia , lookup

Received Pronunciation wikipedia , lookup

Classical compound wikipedia , lookup

Phonological change wikipedia , lookup

Traditional English pronunciation of Latin wikipedia , lookup

Pronunciation of English ⟨a⟩ wikipedia , lookup

Phonological history of English high front vowels wikipedia , lookup

American English wikipedia , lookup

Middle English wikipedia , lookup

Phonological history of English consonant clusters wikipedia , lookup

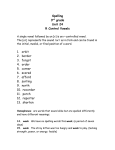

Online section of Chapter 2 in Curriculum and Assessment in English 3 to 11: A Better Plan Written English Sounds and letters Our alphabet has 26 letters. Most linguists agree that the spoken English language has 43 phonemes. (Let us not trouble ourselves about the precise number, which is a matter of debate and may vary depending on a speaker’s accent.) A phoneme is the linguistic term for the smallest unit of sound in a language that makes a difference to meaning. (From now on, I’ll make frequent use of the symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet.) The letter ‘a’, whose name, in certain accents, is pronounced /eɪ/, stands for the phoneme /æ/ in the words ‘cat’, ‘sat’ and ‘mat’. So far, so straightforward. It is also pronounced /eɪ/ (like its name) in the words ‘hay’, ‘say’ and ‘may’. It is also pronounced /ɑː/ in the words ‘father’, ‘rather’ and ‘cart’. It is also pronounced / eə/ in the words ‘care’, ‘dare’ and ‘stare’. It is also pronounced /ə/ in the words ‘about’, ‘thousand’ and ‘royal’. I could easily give similar sets of examples for most of the other letters of the alphabet, and particularly for the vowels. So, to start with, we must concede that symbol-to-sound correspondences are not simple one-to-one letter-to-sound relationships. To be fair, most phonics enthusiasts do allow that, though they are often reluctant to admit just how many ‘exceptions’ to their ‘rules’ there are. Before I go on, I’ll say a little more about my qualifying remark in the previous paragraph to do with accents. In a language such as English, with a great diversity of accents, regional, social and as used – variously – by speakers of English as an additional language, the excessive reliance on fixed symbol-to-sound relationships in the teaching of reading will lead to unnecessary difficulties and confusions. It is true that in many parts of the English-speaking world the word ‘book’ is pronounced with the short ‘oo’ sound /ʊ/. But in some parts of the north of England it is pronounced with the long ‘oo’ sound /uː/. Although in the south of England the words ‘flood’ and ‘blood’ are pronounced differently from the word ‘book’ (/ʌ/ versus /ʊ/), in other parts of the 2 A Better Plan north of England the ‘oo’ sound is pronounced similarly to that in ‘book’, as /ʊ/. Learners of English as an additional language, who are acquiring English as spoken with a particular local accent, may have a particular difficulty when confronted with the requirement to pronounce a particular letter in a certain approved but different way. We come now to pairs of letters. Again, taking a very common example, let us look at ‘t’ plus ‘h’ as in ‘the’. The sounds of the separate two letters ‘t’ and ‘h’ do not make the sound /ð/ when those two letters are put side by side, however hard we may try to convince ourselves that they do. And while we are examining one of the commonest words in the language, the definite article, let us look at another very common word, which also starts with ‘th’, whose next letter is also a vowel, and which also has one syllable: the word ‘thing’. Perhaps the reader would engage in a little audience participation at this point. Please put a finger across your throat and say the word ‘the’. Now put your finger across your throat and say the word ‘thing’. Did you notice any difference between those two experiences? Yes? When you said ‘the’, you felt a vibration in your throat. That was your voice box being activated. When you said ‘thing’, there was no vibration in the throat. The sound was being made solely in the mouth. The first sound was voiced; the second was unvoiced. So, as well as agreeing that the sounds of the separate letters ‘t’ and ‘h’ do not make the sound /ð/ when those letters are put side by side at the beginning of ‘the’, we have also to agree they do not make another sound, /θ/, when put together at the beginning of the word ‘thing’, either. This is a simple example of the problem that the 40+ phonemes in English are represented by a much larger and, to the young child, unpredictable range of letters and letter combinations. As the list of phonemes in the Wikipedia entry on synthetic phonics puts it, the short ‘oo’ sound (/ʊ/ in the International Phonetic Alphabet) is to be heard in the words ‘book’, ‘would’ and ‘put’, and the long ‘oo’ sound’ (/uː/ in the International Phonetic Alphabet) is to be heard in the words ‘moon’, ‘crew’, ‘blue’ and ‘fruit’. The pronunciation of these common words is something that children have to learn by means other than the simple matching of pairs of letters to single sounds. And there are many other examples: we could think of the pairs of vowels ‘e’ plus ‘a’, or ‘o’ plus ‘a’, or ‘a’ plus ‘i’. This last example reminds us of the rain in Spain. In this case, ‘a’ plus ‘i’ makes /eɪ/. ‘a’ plus ‘i’ between two consonants will always say /eɪ/, will it not? It will not. It will in ‘sail’ and ‘aim’, as well as in ‘rain’, but it will not in ‘stair’, ‘pair’ or ‘lair’, nor in ‘plait’. Or let us suppose that Ned left his teddy bear on the stairs before he got into his red bed, which is the A Better Plan 3 sort of thing a little child might easily do. ‘e’ plus ‘a’ between two consonants will always say /eə/, will it not? It will not. It will in ‘wear’ and ‘tear’ (as in damage to clothing rather than an overflow of emotion), as well as in ‘bear’, but not in the latter sense of ‘tear’, nor in ‘clear’, nor in ‘beat’, ‘real’ or ‘team’. To repeat: my examples are common words, of the sort that beginning readers have to encounter and make sense of. Not only is successful reading not just to do with matching single letters to single phonemes; neither is it just to do with matching combinations of letters, whether of consonants or vowels, to single phonemes. Most of the single letters in our alphabet are associated with more than one sound and, in the case of the vowels, with many sounds. Even a simple letter like ‘k’ has two sounds, as in the word ‘knock’, where one of those ‘k’s makes the sound of silence. A correspondences map? Of course, it would be possible to analyse all the symbol-to-sound correspondences in English, and draw up a kind of map to guide the early reader through this difficult territory. It would be a complicated document. Worse from the early reader’s point of view, the correspondences are most various with the commonest words of all: the very words that he or she is coming across most frequently. In 1969, the American linguists Berdiansky, Cronnell and Koehler took the 6,092 commonest one- and two-syllable words from the schoolbooks of a group of six- to nine-year-olds, and worked out that these 6,092 words required the knowledge of 211 symbol-to-sound correspondences in order to be read properly. When they came to look at these 211 correspondences more closely, they made a decision that 166 of the correspondences could be classed as rules and 45 must be classed as exceptions. The 166 correspondences applied to the pronunciation of 5,431 of the 6,092 words. The authors defined a rule as a correspondence that occurred 10 or more times in the 6,092 words. They defined an exception as a correspondence that occurred nine or fewer times. So, when is a rule not a rule? Answer: when it is an exception. Changing English Given the difficulties, as described in these terms, which young readers face, it is remarkable that they learn to read at all, and later I shall describe how they do achieve this success. But before that, I should point out some other features of our writing system which children must encounter, and which defy simple symbol-to-sound correspondences. They relate to the history of English. 4 A Better Plan English, both spoken and written, has changed massively since it emerged from the dialects of the Germanic tribes we know as the Angles and the Saxons 1,500 years ago. It was changed when the Vikings invaded. It was changed hugely when the Normans invaded. It has been changed by the march of technology, particularly from the seventeenth century onwards. It is being changed now, by the internet. The grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation of English (and of the many varieties of English which exist across the world) have evolved and continue to evolve. The scribes Before the invention of printing, as we all know, the written language was carried down the centuries by scribes, many of whom were monks working in abbeys and other religious institutions. (After 1066, scribes who came over with the Normans were often effectively civil servants, writing out the laws that the Norman conquerors made.) It must have been weary work, turning out those manuscripts, although not as weary as trying to get a living off the land under the feudal system. Today, most English speakers pronounce the word ‘light’ like ‘white’ or ‘bite’, apparently ignoring the two consonants ‘g’ and ‘h’, which sit there before our perplexed five-year-old reader. What can they be doing? The answer is that the word ‘light’ originates from the Anglo-Saxon version of the modern German word Licht. The phonetic symbol for the ‘ch’ sound in Licht or in the Scottish word ‘loch’ is /x/. During the first centuries after the Anglo-Saxon invasions, words like ‘light’ and ‘night’ were pronounced approximately as Licht and Nicht are now. Scribes at this time used the single letter ‘h’ to try to represent the sound /x/. So ‘night’ was spelt ‘niht’ and ‘light’ was spelt ‘liht’. Later, some scribes tried the Old English letter called a yogh (‘ȝ’) to represent /x/. But most scribes were opposed to continuing with the few Old English letters which were nothing to do with Latin, like the yogh, so more and more of them got as close as they could to representing /x/ by putting together ‘g’ and ‘h’. It was a reasonable compromise. However, in the centuries following, changes in pronunciation of English meant that the /x/ sound dropped away from most people’s pronunciation of these words (though not in Scotland). As we know, there is a big group of words in modern English – ‘daughter’, ‘drought’, ‘borough’, ‘right’ – that have a silent ‘gh’ in them, always after a vowel or vowels, often before a consonant as in ‘light’, sometimes at the end of a word as in ‘though’ or ‘through’. It is silent because pronunciation changed and spelling did not. Printing, once invented, tended to have a conservative effect on spelling. A Better Plan 5 Incidentally, how strange it is that ‘o’ plus ‘u’ as in ‘thought’ is pronounced differently from ‘o’ plus ‘u’ as in ‘though’, and differently again from ‘o’ plus ‘u’ as in ‘through’, but the same as ‘a’ plus ‘u’ as in ‘taught’. It is often imagined that the ‘gh’ in these combinations is the guilty party in producing these inconsistencies; but that is a false accusation. The ‘gh’ was consistent when it was pronounced, and has been consistent since it has fallen silent. The different pronunciations of the vowels or pairs of vowels in these words are to do with the different etymologies of these words, and to do with the huge change which overcame the pronunciation of English vowels, starting in the early 1400s and lasting for over 200 years. Those changes also affected ‘gh’ words where the ‘gh’ is still pronounced, but as an /f/, not a /x/, like ‘laugh’, ‘cough’ and ‘tough’. There are hundreds of other and different examples of words which have moved well away from simple symbol-to-sound correspondence because of historical changes in pronunciation: ‘knight’, ‘write’, ‘move’, ‘special’, ‘sword’, ‘answer’ and ‘son’ are some of them. Looping the loop ‘Son’ is a particularly interesting example. The scribes had a major problem to do with the absence of loops. In those days, English writing didn’t make a distinction between the letters ‘u’ and ‘v’, one a vowel, one a consonant. The Romans had made no such distinction either. They used ‘V’ for both vowel and consonant. Around the year 1200, our modern word ‘love’, as a noun, was ‘luue’ or possibly ‘lvve’ or something in between, depending on the scribe. As a verb, ‘to love’, it was ‘luuen’ or ‘lvven’ or something in between. It was hard to know where one letter ended and the next began. The upstrokes and downstrokes ran into each other. When ‘u’s and ‘v’s were close to other letters with similar upstrokes and downstrokes, as in ‘sum’ (our word ‘some’), ‘sunu’ (our word ‘son’), ‘cumen’ (our phrase ‘to come’) or ‘wumman’ (our word ‘woman’), we can imagine how difficult it would have been to read the handwritten word. So it seems that at some point some scribes just decided to differentiate the letters from each other by putting a loop on the top of the ‘u’ or ‘v’ which was a vowel, but not on the top of the ‘u’ or ‘v’ which was a consonant, turning that letter into an ‘o’. So the vowel in ‘luue’ or ‘lvve’ become an ‘o’, as it is today. Nothing to do with sound. (Much later, we started to distinguish between written ‘u’ and ‘v’, which made things easier still.) ‘Son’, the male child, was no longer to be confused with ‘sun’, the source of our light (although the original spellings of those two words had never been identical; ‘sun’ had been spelt ‘sunne’). 6 A Better Plan In another unilateral action, some scribes, confronted with Anglo-Saxon words beginning with ‘hw’, such as ‘hwich’, ‘hwær’, ‘hwæt’, ‘hwæl’ (our words ‘which’, ‘where’, ‘what’, ‘whale’), decided, wrongly, that these words were analogous to other words where ‘h’ was the second letter, following another consonant, like ‘chirche’ or ‘shipe’ or ‘thorn’. Perhaps they also decided that this was another case of too many letters with identical upstrokes and downstrokes crowded together, which would certainly be true of ‘hwich’, if we can imagine the ‘w’ as literally a double ‘u’, or a double ‘v’, or something in between (for ‘w’ as we know it had not yet emerged as a separate letter), followed immediately by an ‘i’. (The letter ‘i’ did not yet have its dot above it, either; that was another device scribes invented to make it easier to distinguish letters.) Scribes began to reverse the ‘hw-’ beginnings of words. There were and are many such words. Again, this is a development in the English writing system which has nothing to do with sound. Etymology in modern spelling In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there was a scholarly movement to re-link English words which had originated in Latin with the Latin words from which they had sprung. Many of these words had become semi-detached from their etymological parents. For instance, the English words ‘dette’ and ‘doute’, spelt d-e-t-t-e and d-o-u-t-e (our modern words ‘debt’ and ‘doubt’) had originally come from the Latin words debeo, ‘I owe’ and dubito, ‘I doubt’. (In fact, the ‘b’s had disappeared from early French some time after the Romans disappeared from Gaul.) The scholars put the now silent ‘b’s back where they belonged, and those words and others similarly interfered with (‘subtle’, ‘receipt’) have been giving readers (at least, those over-preoccupied with phonics) some difficulty on first encounter ever since. This last was an example of what we might call ‘retrospective etymologising’. Etymology of a non-retrospective kind has played a very important part in the establishment of modern spelling patterns which have nothing to do with sound. We all know the huge debt (with a ‘b’) that English owes to Latin and, through Latin, to ancient Greek. Let us look at one family of English words which acknowledge that debt: the family which has the particle ‘phone’ in it. (Of course, we commonly and casually use ‘phone’ as a whole word, as an abbreviation of ‘telephone’.) ‘Phone’ comes from the Greek word meaning ‘voice’. The Greeks did not use the pair of letters ‘p’ plus ‘h’ to make the sound /f/. They had their own letter, ‘φ’, and it is possible (but we shall never know for sure) that the sound the Greeks made A Better Plan 7 with ‘φ’ was not quite the same as /f/. When Greek words to do with sound and the voice came into Latin, the Romans decided to use the letters ‘P’ plus ‘H’ to stand in for ‘φ’, perhaps because they were aware that the Greek sound was a little softer, breathier, than straight /f/. Whatever the details, it is from Latin, not from Greek, that the ‘ph’ convention has come. The reader will not need convincing that the separate sounds of the letters ‘p’ and ‘h’ cannot possibly be persuaded to blend into the sound /f/. The origin of this convention is nothing to do with sound, but to do with the spelling decisions of a culture which flourished 2,000 years ago. Interestingly, modern Italian, which one might have expected to have continued the Latin ‘ph’ convention, has abandoned it completely; it spells the words in that family with an ‘f’. And it is the most glorious of ironies that the word ‘phonics’ is perhaps the least appropriate example there is of the rigid adherence to symbol-to-sound correspondences which its more zealous believers wish to impose on everyone else. Spellings to do with meaning One final group of challenges to the simple view of symbol-to-sound correspondences is to do with meaning. Consider the plurals of the words ‘horse’, ‘cat’ and ‘dog’: words that young children are likely to encounter often in their early reading. If we say those words in their plurals – would the reader be so kind as to do it now, please? – we notice that the single letter ‘s’ at the end of those words makes a different sound in each case. In the case of ‘horses’ it is /ɪz/; in the case of ‘cats’ it is /s/; in the case of ‘dogs’ it is /z/. These are small differences, we agree. But the use of the letter ‘s’ to form the English plural is easily the commonest way of doing it; it occurs in the case of tens, probably hundreds of thousands of words in the language. This is a good example of the use of a letter, in this case ‘s’, to do a job connected with meaning, in this case to signify plurals, rather than simply to represent one sound. Another example of this kind of thing occurs when two words which are spelt the same way are pronounced differently depending on their meaning: ‘content’ as in the content of a book and ‘content’ as in ‘I am content’; or ‘reading’, the activity we’re concerned with here and ‘Reading’ the town (spelt, we agree, with an upper-case initial letter, but then ‘reading’ could be so spelt if it were the first word of a sentence). Or consider these two sentences: ‘I will read the book tomorrow’. and ‘I read the book yesterday’. Same word, spelt the same way, used in a different tense in the two examples, and pronounced differently. 8 A Better Plan The written language and reading: a complex relationship I hope I’ve done enough to make my point that we will not properly understand the relationship between the written English language and the teaching of reading except by recognising that the relationship is far more complex (and far more interesting) than can be explained by simple symbol-to-sound correspondences. (An entertaining and accessible short book on the history of English spelling is David Crystal’s Spell it Out (2013).) Let me return for a moment to the 211 correspondences for the 6,092 commonest one- and two-syllable words in those children’s schoolbooks. If a child were made to learn, deliberately, one by one, all those correspondences, all those symbol-to-sound matches, he or she would never learn to read, because deliberate symbol-to-sound matching is too slow a process to be called reading, however speedily a determined decoder of print or handwriting learnt to make those matches. Such a person would be operating at a level of frustration which would soon lead her or him to abandon the activity altogether. When free of frustration, the learner’s brain, engaging successfully with writing, brings to bear a host of sets of cognitive and linguistic strategies to gain meaning from the text, only one set of which is the recognition of graphophonic correspondences.