* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

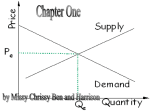

MBA, P1 Sep–Oct 2012 Prices & Markets Timothy Van Zandt Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 The purpose of this handout is to outline the approach I have taken in class and explain where the readings fit in. Some sections are extensive and detailed—the parts that cover the framing of the sessions in a way that differs from the readings. Other sections are skeletal because the readings and slides fill in the details. 1. Students selling textbooks: unit demand and unit supply Our first double sessions 1 & 2 followed closely Chs. 1 & 2. Our starting point for the course was thus trade in a market when each buyer wants to buy only one unit and each seller has only one unit to sell. The motivating example in class was of P4 students selling used Corporate Finance textbooks to incoming P1 students. We approached it from this perspective: • What gains does trade bring to the buyers and sellers? • What kind of trade maximizes those gains? Eventually we reached this picture: Figure 1 $ Consumer surplus MC ↔ Supply P ∗ → 35 Producer surplus MV ↔ Demand Q∗ →500 Q The points on the MC/supply curve are the costs of the individual sellers. It is a marginal cost curve because, at a quantity on the horizontal axis, it measures the extra cost to the sellers (collectively) when one more unit is taken from them. It is a supply curve because, starting at a price on the vertical axis, it tells us how many sellers would sell at that price. The points on the MV/demand curve are the valuations of the individual sellers. It is an MV curve because, at a quantity on the horizontal axis, it measures the extra valuation to the buyers (collectively) when one more unit is given to them. It is a demand curve because, starting at a price on the vertical axis, it tells us how many buyers would purchase at that price. Furthermore, we can read the following from this picture: Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 1. The efficient quantity is given by MC=MV, so it is at the intersection of these two curves. 2. The equilibrium price is given by supply=demand, likewise at the intersection of these two curves. 3. The area of the rectangle P ∗ × Q∗ is the revenue of the sellers and the expenditure of the buyers. 4. The sellers’ total cost is the area under the MC curve; subtracting this from their revenue leaves the producer surplus. 5. The buyers’ total valuation is the area under the MV curve; subtracting out their expenditure leaves the consumer surplus. Understanding that supply comes from MC and that demand comes from MV helps us in several ways: • Price movements are due to shifts in either the supply or the demand curve. We understand that such shifts come from changes in costs or changes in valuations. We thus understand, for example, that a tax on sellers of $10 per unit will shift the MC curve (hence supply curve) up by exactly 10 units. • The impact on prices of a shift in a demand or supply curve depends on the elasticity (price sensitivity) of each of these curves. We understand, for example, that the supply curve is elastic (flat) when sellers have very similar costs. • We can see the gains that traders get. We can see that a seller ends up selling because his cost is lower than that of other sellers, and the amount of his surplus equals his cost advantage over the marginal seller. 2. From students selling textbooks to real firms There are some interesting markets in which sellers have only one unit to sell. In a labor market, the sellers are workers. Although some workers may flexibly choose how many hours to work, as a first approximation the basic unit is a “full-time job” and the most important decision a worker makes is whether and in which industry to work. Likewise, though illegal in many countries, there are markets for kidneys. A person can live a healthy life with one kidney but not zero, so each potential kidney donor—such as I, or you if you still have both kidneys—has only one kidney to sell. However, in this course, we are most interested in markets in which the sellers are firms. A firm’s level of output may be quite large and is always an important decision; we must understand it to have a model of markets with firms. There are further complications: regulations, market power, entry and exit decisions, and adjustment lags and costs that affect market dynamics. In this section, I outline how we deal with each of these complications throughout the course so that we can understand markets in which the sellers are firms. For context, let us consider the market for electricity in Kazakhstan. The electricity production in Kazakhstan has been 85% privatized, the distribution of electricity is through a market (with distributors sharing the same state-owned transmission grid), and the market price fluctuates according to supply and demand. There are 71 power plants, some owned by the same owners. Vestas, a Danish company that manufactures and installs wind turbines, is an example of a firm considering entry into this market. How can 2 Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 Figure 1 help us understand this market? 2.1. Regulation In our market for used textbooks, equilibrium trade is efficient. However, inefficiencies can arise in other markets for a variety of reasons, leading to market regulation. In the electricity market in Kazakhstan, there are regulatory caps on the market price, there are subsidies for renewable energy such as wind, and any generation project must pass through a complicated approval process. We deal with the regulatory environment in an easy way: leave it for later courses, such as your International Political Analysis core course and the Business and Public Policy elective. The tools in Prices and Markets remain critical: you cannot understand the regulated electricity market in Kazakhstan without understanding the underlying market forces that exist under the regulatory layer and without understanding the objectives of the regulators. 2.2. Market power A supply curve measures how much sellers choose to sell at any price, when each seller presumes that he has no influence over the price. This means that the sellers are price takers. Such price-taking behavior makes sense in our textbook market in Sessions 1 & 2. A seller might nudge the equilibrium price up by choosing not to sell, but then that seller could not benefit from the higher price. We can also relate to price-taking behavior as consumers. I eat about 0.00000727% of the tomatoes sold in France. When I buy tomatoes near my home in Fontainebleau, I see a price posted for tomatoes and I figure that I can buy as few or as many tomatoes as I want without affecting that price. In contrast, a typical firm faces a trade-off between volume and price: if it sells more, it does so at a lower price. This trade-off—which means also that the firm can get a higher price by selling less—is called market power. A firm has market power to the extent that either it is a big player in the market or its product is differentiated in the eyes of the buyers. In the electricity market in Kazakhstan, there is no product differentiation: buyers view all electricity as the same and hence there is a single market price. However, one of the 71 plants generates 13% of the electricity. If this plant cut its production by onethird, the supply of electricity in the market would drop by over 4% and the market price would rise noticeably. In particular, the price at which the plant would sell its remaining two-thirds capacity would be higher. Market power is precisely such a trade-off between a firm’s volume of production or sales and the price at which it sells its output. Even a large wind farm built by Vestas in Kazakhstan would represent a small share of the electricity market. Hence, Vestas’ market power would be negligible if it entered. However, suppose that Kazakhstan created a separate market for green energy. Vestas would be the sole supplier of this differentiated good. Some buyers—either firms seeking carbon credits or consumers who want to reduce their personal carbon footprint—would be willing to pay a premium for such green energy. The size of this premium would vary across buyers. Thus Vestas—like any firm whose product is differentiated—would also have market power: if it sells less, it can charge a higher price because it sells only to 3 Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 higher-valuation customers. Market power will be an important topic in this course, starting in Session 7—the part of the course that we call pricing with market power when we study firms’ individual decisions and then imperfect competition when we study firms’ interaction. In the meantime, we ignore market power up through Session 6 by assuming that each firm is a price taker. As a model of firms’ interaction, this is called perfect competition and means simply the model of supply and demand. In summary, our course is divided into two parts: Sessions 1–6 Sessions 7–15 Perfect competition Imperfect competition (firms are price takers) (firms have market power) I chose the word “ignore” meaningfully. Of course, perfect competition is good for quantitatively measuring markets in which firms have little market power. However, it is useful for understanding any market. By first abstracting from the market power that might exist, prices are driven entirely by cost and valuation, with MC = P = MV. When we take into account market power, there is a mark-up over marginal cost: MC < P = MV. Yet cost and valuation remain the most important drivers of prices and market dynamics, in ways that are simple to see with the model of perfect competition but harder to visualize with imperfect competition. 2.3. Entry and exit Unlike consumers, the entry of a firm into a market happens as a discrete jump due to economies of scale. Vestas would not enter Kazakhstan with a single turbine—the generation cost per megawatt–hour would simply be too high. Instead, the minimum scale with which it would enter might be a wind farm with 50 turbines—and it would still face the choice of exactly how large to be: 50, 60, 120 turbines? We therefore need to understand simultaneously firms’ entry/exit decisions and their quantity (i.e., scale or volume) decisions. Here is where we reach the difference between the division of material in the FPM lectures notes (Chapters 3, 4 and 5) and my division of material in class (Topics 3, 4, and 5). In class, I divided the material as follows: • Topic 3: Entry/exit in isolation. • Topic 4: Quantity decisions in isolation. • Topic 5: Entry/exit and quantity combined. For each topic, I integrated the relevant parts of Ch. 3 (costs), Ch. 4 (supply, equilibrium), and Ch. 5 (short-run vs. long-run dynamics). Furthermore, I explained that Figure 1 continues to provide a summary, even if the interpretation of the upward-sloping supply curve differs across topics: in Topic 3, it comes solely from the entry of new firms; in Topic 4, it comes solely from the expansion of output by firms in the market; in Topic 5, it comes simultaneously from the entry of new firms and the expansion of output by firms already in the market. This schema is illustrated in Figure 2. 4 Aggregate supply 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 $ MC↔supply € 5 10 15 20 25 Supply goes up via entry of new firms 30 Q (100MW) € 10 20 30 20 100 200 Qi 300 Q MC ↔ Supply Supply goes up via expansion of output by firms in market 40 20 40 … MCi ↔ Supplyi Quantity ← MC Entry ← break-even price (economic cost) Individual firm Re-interpret unit supply from Sessions 1 & 2 as entry Fix which firms are in the market, only decision is how much to prod. Fix size of a firm, only decision is whether to enter Topic 4 Isolate quantity How Topic 3 Isolate entry/exit Figure 2: Understanding the entry/exit and quantity decisions of firms 40 50 5 10 15 20 25 30 P 10 20 30 ACu € 10Qu 15 20 25 30 35 MC 100 200 300 Supply goes up via entry and exp. of firms in market 5 Entry ← AC Quantity ← MC Q Q 400 AC Firms decide both whether to enter and how much to produce Topic 5 Combine entry/exit & quantity and resulting market equilibrium Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 5 Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 6 2.4. Market dynamics: short run vs. long run Firms’ entry and exit from markets and their changes to output can involve long lead times and costs. As a consequence, when the demand in a market shifts unexpectedly, the dynamic response of the firms and hence of the market unfolds over time. Even with no further surprises in the market, things will look differently one week from now, a month from now, and a year from now, and so on. Though there are a continuum of time horizons, we try only to compare a shorter and a longer time horizon. Thus, we speak of a loosely-defined “short run” and “long run”. We consider two types of adjustments that differentiate the short run from the long run: 1. It may take time for firms to enter or exit the market. 2. Firms already in the market may have trouble adjusting production. In Topic 3, we consider the time it takes firms to enter and exit the market. In the long run, there is exit and entry; in the short run the set of firms and hence output are fixed. This is not presented in FPM but is simple; we do it here in Section 3.6. In Topic 4, we consider the difficulty firms have in adjusting production. This is covered in FPM §5.2–§5.4. In the long run, all inputs are adjustable; in the short run, one or more inputs is fixed. In Topic 5, when we integrate entry/exit and quantity decisions, there is another possible comparison: in the long run, exit and entry is possible and all inputs are variable; in the short run, the inputs remain variable but there is no exit and entry. Whatever the source of adjustment delays and costs, the basic implications for market dynamics are the same: Adjustment delays and costs imply that supply adjusts less in the short run than in the long run—hence, prices are more volatile in the short run than in the long run. I now give a graphical treatment of these general market dynamics. When we then look at a specific source of adjustments costs, all that changes is the interpretation. Figure 2 shows our “leading example” of a market, in long-run equilibrium. Figure 2 $ Slong P1∗ → 35 D1 500 Q Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 7 This picture is familiar, but I have labeled the demand curve D 1 and the equilibrium price P1∗ , anticipating that we’ll see a shift in the demand curve. Furthermore, the supply curve has been labeled Slong , anticipating that we consider also short-run responses of supply. Consider an upward shift in the demand curve. This would come from an increase in the buyers’ valuations for the good sold in this market (for example, because the price of a substitute good has gone up). Such an upward shift by $10 is shown in Figure 3, with the shifted demand curve labeled D 2 . Figure 3 $ Slong P2∗ → 40 P1∗ → 35 D2 D1 500 570 Q We see the new equilibrium with a price of P2∗ = 40. This exercise is very similar to the one we did in Sessions 1 & 2 when there was a shift in the supply curve due to an increase in cost or to a tax, but we model instead a shift in demand. The long-run supply curve is telling us how firms respond to other prices when they have a “long time” to enter or exit and otherwise adjust output. What is a “long time”? It depends on the horizon that we are interested in. If we want to see the market price one year down the road, for example, then this long-run supply curve shows how firms respond to prices when they have one year to enter and exit the market and adjust their output. Consider instead how price evolves over a shorter horizon, say 3 months from now. With a tighter time frame, the firms’ adjustments are harder—it is harder or may be impossible to enter or exit the market; some changes in production are impossible to make quickly, others are costly. Therefore, supply responds less in the short run than in the long run. Take, for example, Vestas after it has entered the market with a windfarm. (For simplicity, I speak as if Vestas would actually operate the windfarm; more likely there would be a distinct operator.) Suppose that its price forecast at time of entry was correct and so it is operating the windfarm at its design capacity. As long as the price does not change, it would keep its output at this level, whether a week or a year from now. Suppose, however, that the price of green energy jumps up and is expected to stay at the higher price. Even at design capacity, Vestas can squeeze out more output right away by increasing the maintanence cost, but this is very expensive. It would take more than a year for Vestas to be able to add turbines to the windfarm, and even longer for Vestas or another entrant to develop another site. Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 8 On the flip side, suppose that the the price drops and is expected to stay low. When Vestas designed its capacity, it factored in all the marginal costs, especially the construction and installation cost of each turbine. If it had expected such a lower price, it would have built a much smaller windfarm or not entered at all. However, if it now lowers output by idling some turbines, its actual savings will be small; therefore, Vestas would likely continue to operate the farm close to design capacity. Let’s visualize this by drawing in a short-run supply curve for Figure 3. Our starting point is the initial long-run equilibrium: The market price is $35 and firms collectively produce 500 units. The short-run supply curve depends crucially on this status quo. If the price remains at 35, output will still be 500, whether a week or a year from now. The short-run response differs from the long-run response only when the price moves away from 35 and firms try, but find it costly, to adjust their output. Thus, the short-run supply curve passes through the long-run supply curve at the current equilibrium. At prices above 35, supply expands less in the short run than in the long run. Likewise, at prices below 35, supply contracts less (and hence remains higher) in the short run than in the long run. This is shown in Figure 4. Figure 4 $ Sshort Slong P1∗ → 35 D1 500 Q In Figure 5, I put the new demand curve back in the picture to visualize how prices respond in the short run and long run following the shift in demand. The intersection of the short-run supply curve with the new demand curve is the short-run equilibrium. Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 9 Figure 5 $ Sshort Slong Pshort → 43 P2∗ → 40 P1∗ → 35 D2 D1 500 570 530 Q The graph is getting busy, so approach it slowly. 1. Pick out the initial long-run equilibrium where D 1 (red) intersects Slong (blue). The price is 35. 2. Then the demand curve shifts to D 2 (orange). Pick out the short-run equilibrium where D 2 intersects the short-run supply curve (green). The price goes up to 43. 3. Finally, pick out the new long-run equilibrium where D 2 (orange) intersects the long-run supply curve (blue). The price goes down to 40 because firms have more time to expand output. 2.5. And from students buying textbooks to other consumers? There are many examples of “unit demand” besides student buying textbooks. Most household buy only one refrigerator; most people have one Facebook account; most people get only one gym membership. In other cases, buyers can flexibly choose how much to consume of a good—such as how much electricity to use in a month, how many gallons of gasoline to buy each week. This extension is outlined in Ch. 2B of the FPM lecture notes. However, we deliberately did not cover this in class; instead, we dwelled on the mirror image for sellers. The important takeway is that Figure 1, and everything we do with it, works whether buyers have unit demand or have multi-unit demand. We merely have different interpretations of the points on the aggregate demand curve. With unit demand, each point is the valuation of one buyer; this interpretation is useful when we want to highlight the differences among consumers. With multi-unit demand, the valuations of the buyers are blended in the aggregate demand curve, so we cannot easily visualize the individual buyers. Yet the aggregate demand curve still measures the aggregate marginal valuation. Otherwise, the complications we have brought up for firms are less important for consumers. Yes, regulation directly restricts consumers purchases, though not in the heavy-handed way that regulation affects firms. Yes, consumers can have “adoption” costs that are analogous to the entry costs of firms, but the adoption decision of one consumer is not the significant market event that the entry of a firm can be. Yes, buyers can have market power, particilarly if the buyer is another firm (B2B), but not so com- Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 10 monly or significantly. Yes, it also takes time for consumers to adjust the consumption in response to changing market prices; yet such adjustment delays and costs are small compared to those of, for example, the construction of new factories or ships. Due to (a) the lower importance of these complications for consumers, (b) that studying them would be the mirror image of our treatment for firms, and (c) that our focus is on the managerial decisions of firms, we do not take up any of these complications on the buyer side of the market. 3. Entry and exit in isolation 3.1. Model: a reinterpretation of the textbook market We can isolate Vesta’s entry decision by fixing the size of the windfarm that it must enter with, such as at 100MW (megawatts). We can isolate entry and exit in equilibrium by fixing each potential firm’s level of production when in the market. Each firm’s sole decision is whether to be in the market. Our model of supply is then the same as in Sessions 1 & 2, but the sell decision is reinterpreted as an entry decision. The price above which a firm would want to enter— the analog of the seller’s cost in the textbook market—is the firm’s break-even price or per-unit cost. The picture of aggregate supply and aggregate MC remains the same, as in Figure 6, except that the magnitude of each unit on the horizontal axis is the fixed quantity of each firm. Figure 6 $ 45 40 MC↔supply 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 5 10 15 20 25 30 Q (100MW) The curve shows the potential firms’ break-even prices, from lowest to highest. Supply expands as the price goes above the break-even price of a larger number of firms, and thus as more firms enter the market. The supply curve also measures aggregate marginal cost. For example, the per-MW social cost of expanding output from 1500 to 1600 MW is the break-even price $17/MWh of the 16th most efficient entrant—this is the entrant whose production should be brought on line in order to expand output. Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 We can then add in a demand curve, obtaining a graph like that of Figure 1. We can, for example, illustrate the impact of a tax on electricity or an increase in production costs by shifting the MC and hence supply curve. Only two things remain to be done: (a) probe the meaning of the break-even price; (b) see what the model tells us about entry and exit. 3.2. Understanding the break-even price The break-even price could also be called the “willingness-to-sell”: the price above which the firm prefers to be in the market and produce and below which the firm prefers to stay out. We call it also the per-unit economic cost. These three terms are synonyms. What exactly does it represent? For sellers of textbooks, it was a subjective measure of how much the seller valued the book, taking into account also the possible opportunity to resell the book outside the market. The cost for a firm might seem more tangible and easy to measure, but we have to be careful not to confuse it with the accounting cost that appears in a profit-and-loss statement. Remember that a firm wants to enter as long as it can cover its economic cost; it wants to exit if it could save its economic cost. Zero profit on a P&L statement would not make the stakeholders happy about having entered the market. The owners of the firm put in equity and perhaps their own time and other resources. The return required on each of these resources so that the owner is happy to use it in the firm rather than in some other way is called the opportunity cost of the resource. The accounting profit must cover the total opportunity costs in order for entry to be worthwhile. Put another way, the true break-even price or per-unit economic cost is the sum of the accounting cost and the opportunity cost of assets and other resources owned by the firm. This concept of opportunity cost is covered in FPM §3.3. Furthermore, at the beginning of Session 4, I worked through an example based on an entrepreneurial activity (past or planned) of one of your classmates. Opportunity costs are explored further in your managerial accounting course in P2, one theme of which is how to measure costs in order to guide decisions. The bottom line for this course? You should understand that “cost” always means “economic cost”, including opportunity cost; hence “zero economic profit” means, for example, that the equity holders are getting the same (risk-adjusted) return on their investment that they could have obtained elsewhere. They are neither thrilled nor regretful about their investment. When a firm exits a market, some expenses that loomed large when entering the market cannot be recovered: they are sunk. These sunk costs do not form part of the economic cost (the savings from exit) when a firm chooses to exit a market. This may create an asymmtry between entry and exit. At the moment of entry, no costs are sunk. At the moment of exit, some costs that were important in the entry decision may now be sunk. As a consequence, the break-even price above which a firm outside the market wants to enter may be higher than the break-even price below which that same firm would choose to exit once in the market. Getting caught between these prices is the familiar dilemma of the entrepreneur when things do not go well: “I wish I hadn’t entered, but there is no point in exiting now.” Sunk costs are reviewed in FPM §3.3 and I used your classmates’ entrepreneurial example in Session 4 to illustrate which costs might be sunk at the moment of exiting the market. Sunk costs are studied further in managerial accounting. The resulting asym- 11 Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 12 metry between entry and exit is an important theme in some of your competitive strategy courses—along with the associated concept of irreversible investments, the implication for the value of flexibility in the face of uncertainty, and the effects on market dynamics. We do not have the time to do much with this asymmetry—at best, it lurks in the background. The bottom line for this course? Any time we are considering a firm’s decision, the economic cost that guides this decision does not include costs that are already sunk. 3.3. Economic profit and competitive advantage From here to the end of Section 3, I will explore various ways in which this model helps us understand entry and exit. Everything I show here will remain true when we intergrate the entry/exit and quantity decisions, it is just clearer and simpler to see because we have isolated entry and exit. In particular, Sections 3.3–3.5 are an isolation of ideas about entry and exit and competitive advantage that appear in FPM Ch. 4. First, this simple model of entry and exit provides insights into market composition, the entrepreneurial decision to enter or exit a market, and economic profit—all coming from the idea of competitive advantage, which here means having a lower cost than other firms. The jaggedness of the supply curve in Figure 6 helps us see that each point is the break-even price or entry decision of another firm, but it can otherwise muddle the picture. So let’s smooth out the diagram, without forgetting that each point is a distinct firm. Let’s add in a demand curve and visualize equilibrium. This gets us back to Figure 1, which I reproduce it here for your convenience. I have reduced the scale on the horizontal axis so that each firm does not seem so insignificant (one out of 50 rather than one out of 500). Figure 7 $ Consumer surplus MC ↔ Supply P ∗ → 35 Producer surplus MV ↔ Demand Q∗ →50 Q In class, we made these observations: 1. Which firms are in the market? Those with the lowest costs, that is, those with a competitive advantage over other firms. 2. How much is a firm’s producer surplus? Per unit, it is the gap between the market price P ∗ and its own cost Ci . The market price is also approximately the cost of the marginal firm in the market (the last firm to enter or the next firm that would Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 13 enter). Thus, the magnitude of a firm’s surplus is the magnitude of its competitive advantage over the marginal firm. Furthermore, we observed in class that a firm’s surplus equals its contribution to the market, as follows. Suppose a firm i in the market with cost Ci were to disappear. Either the amount consumed by the buyers must fall or this firm must be replaced by a firm not in the market. • In the first case, the loss on the margin to the buyers is P ∗ because this is the marginal value on the demand side: either the valuation of the lowest-valuation buyer who is getting the good or the marginal valuation of each buyer in the case of multi-unit demand. Thus, buyers lose P ∗ per unit but the firm’s cost Ci per unit also disappears: the net decline in gains from trade is P ∗ −Ci per unit. This is precisely the economic profit earned by the firm. • If instead firm i is replaced, the next firm brought into the market has a per-unit cost of approximately P ∗ . The production cost thus increases from Ci to P per unit that i was producing. In other words, the presence of firm i reduces production costs by P − Ci per unit, and this is also precisely firm i’s economic profit. The magnitude of firm i’s economic profit (and thus its contribution to the market) is small when its cost is similar to that of the marginal firm. This is necessarily true for all firms active in the market if all potential entrants have very similar costs, as illustrated in Figure 8. Figure 8 $ MC ↔ Supply P ∗ → 35 Producer surplus MV ↔ Demand Q∗ →50 Q Each firm gets very little profit because it is replaceable. It is in the red ocean of a mature industry in which imitation is easy. No firm contributes much to the market because it can be replaced by another firm with similar cost. From the outside, it would be hard to identify which firms have a competitive advantage and hence should be in the market. Figure 7 shows, in contrast, a blue-ocean industry in which successful firms have unique capabilities that cannot be imitated by other firms. Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 14 Figure 9 $ MC ↔ Supply P2∗ → 40 P1∗ → 35 D2 D1 50 57 Q Figure 10 $ MC ↔ Supply P2∗ ≈ P1∗ → 35 D2 D1 50 63 Q 3.4. Long-run market dynamics and the elasticity of supply The similarity of the firms’ costs in Figure 8 means also that the supply curve is flat and hence very elastic. That is, small changes in the price lead to large changes in supply, due to the entry and exit of similar firms. How much the market price changes when the demand curve shifts depends on the elasticity of supply. Figures 9 and 10 show the supply curves in Figures 7 and 8, along with the demand curve in those figures (labeled D 1 ) and the same demand curve shifted up by $10 (D 2 ). The price is initially $35 for both supply curves. After the shift in demand, the price increases significantly in Figure 9. Yet the price hardly moves in Figure 10 because supply is so elastic: the narrow range of break-even prices nearly pins down the market price, whatever is the demand curve. An increase in demand merely leads to the entry of new firms into the market until the price is close to where it was before. Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 15 3.5. Taking firm similarity to an extreme: free entry In a red ocean in which firms have similar costs because they lack unique capabilities and imitation is easy, we have observed the following: 1. The market price is nearly pinned down by the similar costs of the firms; an increase in demand leads to new entry until the price settles to nearly where it was before. 2. Each firm earns very little economic profit, because each is nearly replaceable. 3. Differences between firms are so small that it may be difficult from the outside to see which firms should/would be in the market. Let’s take this scenario to the extreme: all firms, including a large pool of potential entrants, have the exact same cost structures. This idealization is called free entry. Figure 8 becomes Figure 11 if the common break-even price is $35. Figure 11 $ MC ↔ Supply P ∗ → 35 Demand ∗ Q →50 Q It is important to understand that free entry is an assumption about the similarity of firms, not about whether firms are “allowed” to enter a market or not. We had been doing quite fine studying entry and exit by firms that could freely choose whether to be in or out. However, previously we had taken in account firm differences—which in reality exist whether minor or significant. In contrast, the idealization called free entry means that all firms are identical. Our observations about the red ocean of firms with similar costs become absolute statements when the firms have identical costs: 1. The market price must equal the common break-even price of the firms; an increase in demand leads to new entry until the price settles to exactly where it was before. 2. Each firm earns no economic profit, because each is replaceable. 3. Because firms are identical, the model does not pin down which firms end up in the market. Although we lose any ability to identify who is in the market, the assumption of free entry allows us to quickly see the essential features of a market in which firms are highly similar. It immediately pins down the market price and then, with access to demand data, the number of firms in the market. Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 16 For example, consider the wholesale market for cut roses. Colombia and Ecuador are the world’s largest producers. Colombia has about 215 exporters of flowers, many of whom grow roses. Let the unit for measuring output be one million roses. For example, the United States imports about 2 billion roses per year, or 2000 of our one-million-rose units. The wholesale price for one unit could be, for example, $250K. (These numbers provide some context but I will not try to precisely calibrate my numerical example.) To isolate entry and exit, we assume that each grower must have production of exactly 8 units per year. To make this a model of free entry, we assume that each grower has the exact same production cost of $250K per unit. Thus, without yet any information about demand, we know that the market price must be $250K and that each grower just breaks even. We cannot determine which firms are in the market, but we can figure out how many. For this, we need information about demand. Given the market price, the demand curve tells us total demand. Then, since supply=demand, this is also the total supply. We divide by the size of each firm (8 units) to get the number of firms in the market. For example, suppose that the demand curve (here measuring prices in $1,000) is Q = 1060 − 2P. Thus, at the market price of P ∗ = 250, total demand is Q∗ = 1060 − 2 × 250 = 560. This number must also be the total supply. Since each firm supplies 8 units, the number of firms is N∗ = 560 ÷ 8 = 70. In summary, we have these simple calculations in this model of free entry: Symbol Q∗i P∗ Q∗ N∗ Measuring … Comes from … Output per firm Market price Total output Number of firms Fixed in order to isolate entry/exit The firms’ common break-even price Demand d(P ∗ ) at the market price Q∗ ÷ Q∗i Here 8 $250K 560 70 3.6. Market dynamics based on entry and exit We can use this model of entry and exit for our first concrete story about the difference between the short run and the long run. For our short run, we assume that firms cannot exit or enter. Since we have suppressed quantity decisions, this means that supply cannot adjust at all: it is perfectly inelastic, as drawn in Figure 12. Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 17 Figure 12 $ Sshort Slong Pshort → 45 P2∗ → 40 P1∗ → 35 D2 D1 50 57 Q The story is interesting. When the demand shifts, the price jumps up to 45. Then it begins to fall as one firm after another enters the market, until the number of firms grows from 50 to 57. Something not evident until now is that firms have to really understand the world to make their decisions: they cannot simply respond myopically to market prices. The total number of firms with break-even prices below 45 is about 65 in Figure 12. Thus, when the price first jumps to 45, there are 15 firms not in the market who would find it profitable to enter. Yet in the long-run equilibrium, only 7 of these firms end up in the market. Remember, entry takes time, so firms have to decide now whether to enter, before seeing the long-run price. Each firm has to forecast that price in order to determine whether to enter. Firms do this by having either hard data or intuition about demand and hard data or intuition about where they stand (in terms of cost) relative to other potential entrants. The latter is particularly challenging—one has to have insights about firms that do not even exist. Especially when the data are poor, understanding the forces driving market dynamics is better than naively responding to market prices and being buffeted about by the market winds. 4. Quantity decisions in isolation Next we consider the quantity (that is, scale or volume) decision of a firm given that it is in the market, and the resulting market equilibrium given a fixed set of firms in the market. We covered this, including a full numerical example, in Session 3. The best summary is the blackboard write-up that I sent by email and posted on the course web page. (A more complicated numerical example is our perfect competition simulation, in which 39 firms competed in a market and made quantity but not entry or exit decsions.) For a firm’s quantity decision, only marginal cost matters. Therefore, this topic draws on the discussion of marginal cost—but nothing else—from FPM Ch. 3. The supply decision is studied in FPM Ch. 4 on page 98. The bottom line is that a firm’s supply curve is the inverse of its marginal cost curve. We then find aggregate supply by summing the individual supply curves. This is straightforward; I did it in class and you can see also FPM §4.4. In class, I explained Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 why the aggregate supply curve measures aggregate marginal cost. This is a deeper concept, but the bottom line is that Figure 1 remains valid. In this setting, we can revisit short-run vs. long-run dynamics. Here the long run means that there is a fixed set of firms in the market who have a long time (as long as they need) to adjust production efficiently. The short run means that firms cannot change their usage of one or more inputs—that is, some inputs are fixed in the short run. This is covered in FPM Ch. 5. In class, I only cover it graphically and briefly, in the debrief of the simulation. Therefore, I will not ask detailed questions on the exam about short-run costs vs. long-run costs as covered in FPM §5.2–5.4. Nevertheless, you should understand well the the general picture of short-run vs. long-run market dynamics in Section 2.4 of these notes. That section subsumes FPM §5.5, and FPM §5.6 and 5.7 are already excluded by the Prep Guide as required reading. Thus, none of FPM Ch. 5 is essential reading for the quiz and exam. 5. Combining entry/exit and quantity decisions This was covered in the second half of Session 4 and most of Session 5. We went through a full numerical example. Conceptually, there is little not already covered in Topic 3 and Topic 4. The main innovation concerns the individual firm’s AC curve, what it says about economies of scale (or why its shape comes from economies of scale), and how it characterizes the firm’s entry decision. Whereas in Topic 3 we simply assume a scale for each firm, here the reason that entry is a discrete jump into the market is due to economies of scale: initially decreasing average cost. Furthermore, the minimum scale at which entry takes place depends on the magnitude of these economies and is given by the quantity Qu that minimizes the firm’s average cost. Furthermore, whereas in Topic 3 a firm’s break-even price is simply given, here we derive it as the firm’s minimum average cost ACu . Thus, key FPM readings are from Ch. 3 on costs: fixed costs as a source of economies of scale, and the mathematics of U-shaped average cost (pages 87–89). The other key reading is pages 105–107 of Ch. 4 on equilibrium with free entry. In the notes that follow, I give a skeletal summary of the main ideas. See the slides from Session 5 for numerical examples. 5.1. Costs The average cost curve becomes important for two interrelated reasons having to do with entry. First, it captures economies of scale, which is why a firm’s entry is a discrete decision. That is, a firm jumps into the market with a significant scale rather than sliding in unnoticeably. Second, the entry decision can be derived entirely form the AC curve. We assume that the AC curve is U-shaped: there are initially economies of scale and then, at higher quantities, diseconomies of scale. This is both realistic (even if more complicated situations could arise) and provides good intuition about entry decisions. The simplest way to have a U-shaped AC curve is to assume FC > 0 and increasing MC. This is the only case we consider. Besides being simplest, it provides the best intuition about entry. The fixed cost can be thought of as an entry cost. The firm enters 18 Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 19 if this entry cost is made up for by the variable profit that it earns in the market (where variable profit is calculated excluding the fixed cost). 5.2. A firm’s quantity A firm’s optimal quantity or scale, given that it enters, is given entirely by the MC curve, as illustrated in Figure 13. This is a repeat of the firm’s decision in Topic 4. Fixed cost and average cost do not matter. Figure 13 € MC↔supply 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 s(6) = 40 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 Q 5.3. A firm’s entry or exit decision A firm’s entry or exit decision is given entirely by the minimum point on the AC curve. The minimum average cost, denoted ACu , is the firm’s break-even price. The firm enters if the market price is higher (or expected to be higher) than ACu and it stays out otherwise. The quantity Qu that minimizes average cost is the firm’s minimum scale of production if it enters the market. Figure 14 € 8 7 AC 6 ACu 5 4 3 2 1 10 20 Qu 30 40 50 60 70 Q Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 20 5.4. Combining the two decisions We can superimpose the AC and MC curves to see the entry/exit and quantity decisions together. The two curves cross at the minimum point on the AC curve. This is shown in Figure 15. The firm stays out of the market, and hence supplies 0, until the price reaches ACu . At that price, the firm would enter the market with quantity Qu . At higher prices, the firm’s output follows the MC curve. Overall, the firm’s supply curve is the thick light blue line. Figure 15 € MC 8 7 AC 6 u AC 5 4 3 2 1 10 20 Qu 30 40 50 60 70 Q 5.5. Aggregate supply and equilibrium As the price rises, aggregate supply increases for two reasons: entry of new firms as the price crosses their break-even prices (as in Topic 3); and expansion of output by firms in the market (as in Topic 4). The supply curve could look as shown in Figure 16. Equilibrium is then found in the usual way by supply=demand. Figure 16 P 30 25 20 15 10 5 Q 100 200 300 400 Prices & Markets • Overview of perfect competition: Sessions 1–6 5.6. An alternate view of entry/exit and equilibrium Constructing the aggregate supply curve allows us to see that Figure 1, and everything we can do with it, remains valid. Furthermore, we understand that we can interpret the increase in supply in Figure 1 as coming from both entry of new firms and expansion of output by firms already in the market. However, there is an alternate two-stage view of equilibrium that is closer to the way the firms think about entry. In the first stage, firms decide whether to enter or stay in the market. In the second stage, firms compete—as in the model of fixed firms in the market from Topic 4. The individual firms’ decisions and equilibrium are understood by working backwards. In the second stage, the equilibrium price and the variable profit that each firm earns (disregarding its fixed cost of entry) depends on the set of firms in the market. The first-stage entry and exit decisions are in equilibrium if the each firm in the market does not lose money (and hence would not prefer to exit) whereas any firm not in the market could not make a profit by entering. In terms of break-even prices, this means that the equilibrium price is not lower than the break-even price of any firm in the market, whereas if a firm not in the market were to enter then the equilibrium price would be lower than its break-even price. In terms of fixed costs and variable profits, this means that each active firm’s variable profit covers its fixed cost of entry, yet if another firm entered the market then its variable profit would be lower than its fixed cost of entry. Although the dynamics of market entry and exit can be very complex, the most intuitive story is to suppose that firms enter one at a time, with the most efficient firms entering first. We can then see how eventually equilibrium must be reached. Each time another firm enters the market, supply expands, the market prices falls, and the variable profit of each firm goes down. At the same time, the pool of remaining firms are increasingly inefficient. Hence, eventually the declining market price and declining variable profit makes subsequent entry unprofitable and the market reaches equilibrium. This two-stage approach is not outlined in any of the lecture notes except in the form of Exercise 4.3, which I think most students will find too involved. Furthermore, I have not found time to discuss it in class, so it does not form part of the our required material in this part of the course on perfect competition. On the other hand, I will use it for entry and exit with imperfect competition. 5.7. Free entry When there is free entry (that is, firms are identical), the main conclusions are the same as in Topic 3: Firms earn zero profit, the price is pinned down by the common break-even price of the firms, and supply is perfectly elastic. The calculations change a bit because each firm’s output Q∗i and the break-even price P ∗ are derived from the cost curve as the quantity Qu that minimizes average and the minimum value ACu of the average cost. (A firm’s output and break-even price were simply given in Topic 3.) Otherwise, the calculations are the same: total output comes from the demand curve: Q∗ = d(P ∗ ); the number of firms comes from N∗ = Q∗ ÷ Q∗i . 21