* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Lagoon Nebula and its Vicinity

First observation of gravitational waves wikipedia , lookup

Nucleosynthesis wikipedia , lookup

X-ray astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Astrophysical X-ray source wikipedia , lookup

Main sequence wikipedia , lookup

Hayashi track wikipedia , lookup

Cosmic distance ladder wikipedia , lookup

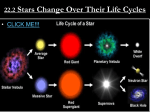

Stellar evolution wikipedia , lookup

Planetary nebula wikipedia , lookup

Astronomical spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup