* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

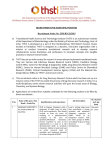

Download Study on off-label use of medicinal products in the European

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript