* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Introduction to Macroeconomics

Nouriel Roubini wikipedia , lookup

Fiscal multiplier wikipedia , lookup

Long Depression wikipedia , lookup

Economics of fascism wikipedia , lookup

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

American School (economics) wikipedia , lookup

Economy of Italy under fascism wikipedia , lookup

Transformation in economics wikipedia , lookup

Early 1980s recession wikipedia , lookup

Introduction to

Macroeconomics

"[h]ad the price of gold been raised in the late 1920's, or,

alternatively, had the major central banks pursued policies of price

stability instead of adhering to the gold standard, there would have

been no Great Depression, no Nazi revolution, and no World War II."

Introduction to the basic propositions of macroeconomics

Macroeconomics is the branch of economic analysis most closely identified with "economic wellbeing" and the justification for studying macroeconomics is based upon four propositions - (1) economic

well-being matters; (2) economic well-being can be "captured" by macroeconomic variables (e.g..

unemployment and inflation rates); (3) there are stable relationships between macro variables; and (4) these

economic variables can be managed by policy officials.

Macro matters

The first of these propositions – macroeconomics matters - is widely accepted. Robert Mundell, recipient of

the 1999 Nobel Prize in Economics, wrote: "[h]ad the price of gold been raised in the late 1920's, or,

alternatively, had the major central banks pursued policies of price stability instead of adhering to the gold

standard, there would have been no Great Depression, no Nazi revolution, and no World War II."i He was

simply restating the sentiment of observers of the rise of Fascism in Italy and Germany and Communism in

Russia. Paul Scheffer, writing in 1932 about the followers of Hitler, describes them as,

this depressing assemblage of people is waiting for. It is waiting for a gospel, a message, a Word

that will release it from the pinch of want, something that will compensate for the unbearable

limitations of its present mode of existence. It wants to get hold of an ideal that will guide it forth

from the quagmire where it finds itself. It wants to hear an assurance that it is entitled to a place in

this new world. The man who can lift these people from their depression of spirit even for the

space of an hour can win them to himself and to the cause that he tells them represents the

substance of "liberation. … [Hitler] “is fighting for the right of the half-educated to their own

picture of the world, to a culture which is illumined by love of country. He shouts at the university

students that they are not worthy of pursuing their scholarly studies if they cannot find a common

ground with the mechanic who is intent on serving his country.ii

The hyperinflation and widespread unemployment in Germany in the 1920s was not something we can

relate to from our own experiences, but you can see from the passage below how it would wreck an

economy and a society and set the stage for the rise of a fanatic promising a better future.

'FOR these ten marks I sold my virtue,' were the words a Berliner noticed written on a banknote in

1923. He was buying a box of matches, all the note was worth by then. That was in the early days.

By November 5th, a loaf of bread cost 140 billion marks. Workers were paid twice a day, and

given half-hour breaks to rush to the shops with their satchels, suitcases or wheelbarrow, to buy

something, anything, before their paper money halved in value yet again.iii

By the time the hyperinflation had ended in April of 1924 the US dollar was worth 4.2 trillion marks, up

from a price of only 2,000 marks a year earlier - and Germans were looking for someone to lead them out

of the mess - and someone on whom to blame the mess. They found the leader in Hitler and the scapegoat

in the Jews, and we know the end of the story. And Germany was not alone.iv Mismanagement of the

macroeconomy has produced numerous episodes of hyperinflation, including in Greece (1943-1944) where

the inflation rate peaked at 8.55 billion %; in Hungary (1945-46) where it reached 4.19 quintillion percent;

1

and in China (1948-1949) where the “Chinese Communist Party never forgets it seized power in 1949

following not just military victory, but also hyperinflation under the Kuomintang government…”v

More recently, there was hyperinflation in the former Yugoslavia where Slobodan Milosevic engineered

the ethnic cleansing in Kosovo in an economy already brutalized with inflation.vi The magnitude of the

Yugoslavia hyperinflation of the early 1990s is evident in the numbers that are truly mind-boggling.vii

In October of 1993 they created a new currency unit. One new dinar was worth one million of the

old dinars. In effect, the government simply removed six zeroes from the paper money. This of

course did not stop the inflation and between October 1, 1993 and January 24, 1995 prices

increased by 5 quadrillion percent. This number is a 5 with 15 zeroes after it.

Even the catastrophic results in Yugoslavia did not, however, rid the world of hyperinflation. By mid

December in 2008 Zimbabwe was in the midst of one of the world's worst bouts of hyperinflation. It began

circulating a $500 million note as inflation approached 11,250,000%, a rate high enough for prices to

double every 22 days and to bring about a collapse of the economy.

The importance of the macro economy can also be seen in the million+ witches killed in Renaissance

Europe when the weather was unusually cold,viii rioters in the streets and presidential resignations in

Argentina in 2001 that accompanied depression-like unemployment rates of 25 percent,ix the collapse of the

government of Thailand months after the economic crisis of 1997, the Arab Spring that began with the

overthrow of Tunisia’s former president Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali by millions without access to decent jobs.

At a more personal level tough economic times are reflected in poorer health and higher suicide rates. In

tough times governments cut back public health programs and individuals cut back on their discretionary

medical spending, while “[t]he correlation between unemployment and suicide has been observed since the

19th century. People looking for work are about twice as likely to end their lives as those who have jobs. …

Fiscal policy, it turns out, can be a matter of life or death.”x

In the US, however, the state of the macroeconomy is less likely to show up in social unrest, although it

may show up in higher suicide rates that we experienced in the Great Recessionxi or crime stats. In 2008, in

the midst of the economic crisis that rippled around the world, the New York Times ran a story under the

byline "As economy dips, arrests for shoplifting soar." And the state of the economy certainly affects

election results. This is evident in the following passage.xii

At any given moment the state of any nation—and especially the state of any stable industrial

democracy, where a measure of political calm and social order can generally be taken for

granted—is determined largely by the state of its economy. Wars, relative military strength,

terrorist attacks, natural disasters, demographic changes, social trends, election outcomes, even the

results of international sporting competitions, can all contribute significantly to a country's

perception of its own well-being. At times, certainly, one or more of these factors can outweigh

the economy in affecting the collective sense of how the country is faring. But as any presidential

candidate will tell you, for the average American citizen the most basic measure of national wellbeing amounts one way or another to economics. Is my income higher or lower than it was last

year? Is my job more or less secure? Across the spectrum of class or income well-being is

measured to a considerable degree by the question "Can I afford ... ?" Can I afford to put the kids

through college? Buy a house? Put my mother in a nursing home? Pay for day care? Put food on

the table? Buy a vacation home?

It should not be surprising, therefore, that in many presidential elections the economy has been a deciding

factor. At the top of the list would be the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932 that promised a way out of

the Great Depression. John Kennedy picked up on the economy theme and defeated Richard Nixon in 1960

when the American people rallied around his promise to get the economy moving again, and Jimmy Carter

won the 1976 election with rhetoric like the following:

2

This year, as in 1932, our country is divided, our people are out of work, and our national leaders

do not lead. Roosevelt's opponent in that year was also an incumbent president, a decent and wellintentioned man who sincerely believed our government could and should not with bold action try

to correct the economic ills of our nation.

Unfortunately for Carter, the economy headed south and he lost in 1980 when Reagan challenged the

American people to reflect on the past four years and ask the question:

Can you look at the record of this administration and say, 'Well done'? Can anyone compare the

state of the economy when the Carter administration took office with where you are today and say,

'Keep up the good work'? Can you look at our reduced standing in the world and say, 'Let's have

four more years of this'?

The answer was NO, and Ronald Reagan was elected president. Bill Clinton followed the tradition and put

the economy at the center of the 1992 election with his campaign slogan "It's the economy, stupid." And

then in 2008 Barack Hussein Obama won an election that no one would have predicted a year earlier – in

part because he followed Kennedy’s lead in mastering a new technology – TV for Kennedy and the Internet

for Obama – and in part because the US economy was sliding into the Great Recession.

The economy’s impact on presidential elections is evident in the graph below.xiii Although not a “perfect”

relationship, it is clear that the incumbent party’s share of the vote increases as the economy grows faster.

For example, in the election in which GDP was falling faster than 1%, the incumbent party’s share of the

vote was about 10%, while when the economy was growing faster than 10% it was close to 100%.

Jill Gloekler, The Effect of the U.S. Economy on Presidential Elections: 1828-2008,

It is not difficult to accept this relationship, but it is a bit more difficult to understand how the country has

shifted so much to Republicans given that since the Eisenhower years in the 1950s the "real incomes of

middle-class families grew more than twice as fast under Democratic presidents as they did under

Republican presidents."xiv How is it that the Republicans have so successfully managed to get those at the

lower end of the income distribution to vote for policies that clearly hurt their economic position? Some

suggest it is a timing issue - that under Republicans the economy tends to perform best just before the

election. Others suggest Republicans have been able to divert attention from the economic issues to social

issues, so you have gay rights and abortion as key issues. And still others suggest there is a clear racial

element in the strategy began with Reagan's Southern Strategy.xv

What is clear is the likelihood of wars and the outcome of elections hinge on an economy's

performance.xvi This is why the Chinese in 2011 continued to resist efforts by the US to increase the value

of the Yuan that would close the balance of trade deficit. The weak Yuan keeps factories humming in

3

China, which keep incomes growing and reduce the chances of a social uprising that would bring down

China’s rulers – a reoccurring pattern in China’s past.

If macro matters, we can measure it

Given that the goal of macroeconomics is managing the macroeconomy, and the secret to good

management is good information, then management of the economy requires a set of macroeconomic

variables that captures the economy’s performance. The good news is there are many such variables: GDP,

inflation, and unemployment being the most widely discussed. The bad news is these variables can at times

appear to be telling different stories about the economy's performance. It is not unusual to see

unemployment rates falling – a good thing – while earnings fall – a bad thing. The indicators also usually

measure how the economy performed in a previous period - last month or last quarter - so it is difficult to

judge how an economy is doing at the present time. This problem was quite evident in early 2008 when

president Bush and some economists refused to acknowledge a recession by noting a falling unemployment

rate and the lack of any figures on GDP, while the news media focused on indicators including rising

bankruptcies, declining stock prices, declining home sales and prices, and employment declines as evidence

that a recession had begun. In the macromeasurement unit a number of these variables that are frequently

mentioned in the news are examined in some detail - their definitions as well as the historical track record

that can be used as a benchmark to evaluate the current state of the economy and begin to ponder the future.

And do not be surprised that politicians have played tricks with those numbers, something we will examine

more closely in a later unit.

Stable macro relationships?

Macroeconomic policy works if the macroeconomy “follows” some known rules. For example, let’s look at

the events following September 11, 2001. The story went something like the following. The attack on the

US made investors nervous and this drove down the price of stock as they sold their stock. In a matter of

days the value (price) of stocks dropped substantially prompting consumers, who were feeling poorer, to

cut back on spending on vacations, new cars, or a new house. Eventually, businesses producing the

vacations, autos, and homes cut back production, which is reflected in a decline in GDP and higher

unemployment rates as the production cuts translate into worker layoffs.

A similar story emerged in late 2007 as the sub prime crisis in the US morphed into a full-scale financial

crisis. It did not take long for the problems experienced by a small segment of home owners to work its

way through the economy - higher mortgage default rates among those with high risk loans triggering

higher interest rates and lower consumer and business confidence - and quickly we were in the midst of a

downward economic spiral that resulted in a recession that in late 2008 was promising to be long and deep,

something the US economy had not experienced since the early 1980s.

A final example is the relationship between interest rates and inflation rates. It is very clear in the graph

below that the two tend to move together - in the 1970s both were rising and in the 1980s - and although it

is not a perfect, anyone interested in forecasting inflation rates would need to consider interest rates.

4

It is these stable relationships that must exist if policy makers are to be able to effectively manage the

economy, and a good deal of research effort has been exerted to identify these relationships. We will not

get into the details, but we’ll certainly examine the evidence in later units in the course.

If we can measure it, can we manage it?

In the aftermath of the Great Depression and WW II, the U.S. government passed legislation – Employment

Act of 1946 – that made managing the macro economy was one of the responsibilities of the federal

government. From that time forward the US government, at least on paper, was committed to doing what it

could to achieve full employment, and in this course we will look at how well we have done at this and at

the tools government has to achieve this goal. There are two distinct tools that can be used to manage the

macroeconomy. The first is called monetary policy and refers to the decisions of the Federal Reserve (Fed)

to alter the nation's money supply and the price of that money - interest rates. The second is called fiscal

policy and refers to changes in government spending and / or taxes that are initiated by Congress or the

President.

So how did policy makers react to the macroeconomic shocks of 2001 and 2008-09? In the aftermath of

both shocks nearly everyone was proposing a fiscal policy response - they just couldn't agree on the best

response. Some proposed increases in government spending - unemployment benefits or spending on

infrastructure - while others proposed tax cuts to "induce" people to spend more on vacations, autos, and

homes. President Bush went to the American people and asked them to do their patriotic duty and go out

and spend those tax cuts. It was also why president Obama called for a massive government spending on

infrastructure and green technology to “soften” the effects of the Great Recession. If the private sector

would not buy "stuff," then the government would, and we see that in the graph below of the net federal

government savings. This is the difference between what the government takes in as tax revenues and what

is spends, and it clearly reveals the fiscal policy response to the 2001 and 2008-09 recessions. In 2001 and

then again in 2008, the net savings of the US government turned significantly negative as the tax cuts and

spending increases created big budget deficits that pumped spending into the economy.

5

As for the Fed, these were also times where the Fed could employ the other macro policy tool - monetary

policy - to manage the economy. In both cases as private spending was collapsing the Fed stepped in to

"induce" individuals and businesses to spend more by lowering interest rates, which you can see in the

graph below. The Effective Federal Funds Rate is an interest rate the Fed controls, and you see the Fed

moved aggressively in 2001 and again in 2007-08, just as it had done in the recession of the early 1990s.

By 2009 the federal funds rate was virtually 0, which the Fed hoped would prompt businesses and

individuals to get out there and borrow to support spending.

Course themes

This management of the macroeconomy sounds pretty simple – little tax cut here and interest rate cut there

and policy makers can keep the economy from falling into a recessions. The problem is it is not that easy

and there are some very deep, and often bitter, disagreements that were evident in the debate over the

Obama stimulus package. To help you better understand major macro issues that will not disappear soon,

there are three themes that run through the course.

First, to make sense of these debates, it is important to recognize the importance of ideology. In the United

States most economic policy debates you are likely to see in the mainstream press take place between two

groups - Liberals and Conservatives. Conservatives tend to believe a good government is a small

government that simply sets the "rules" to govern the competition between businesses and individuals, and

in the US their ideas are reflected in the policies of Republicans. Liberals, whose ideas are represented by

Democrats, accept the power of markets, but believe there are advantages to devising policies to offset

some of the structural flaws of the market system. The "war" between conservatives and liberals rages on

many fronts – immigration, environmental policy, business regulation being some of the more high profile

ones in recent years – and it is not likely to end any time soon. In this course we will focus on only one

dimension of that war – macroeconomic policy – and to understand these policies we will follow the advice

of Keynes and look at the theories upon which those policies are founded.

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are

wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else.

Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are

usually the slaves of some defunct economist.xvii

For those who want to follow the war, the conservative side of the battle can be found on Fox news or the

Wall Street Journal, while the liberal perspective can be found on MSNBC or the New York Times.

It should be noted, however, that the debate between conservatives and liberals is just part of a much

broader ideological debate about economic systems and policies. Baby boomers won't soon forget the Cold

War that raged for so many of their "formative" years that was essentially a war of competing economic

6

ideologies - capitalism and communism - and Delong, in Slouching Toward Utopia, notes that during the

20th century there was a considerable amount of "killing in the name of economics."xviii By the dawn of the

21st century, after the wall between Eastern and Western Germany had come down and the Soviet Union

was dismantled, the prevailing view was that capitalism had proved itself superior to communism and the

ideological debate had been settled.

At the center of the debate are differences of opinion regarding the adequacy of the self-adjustment

mechanisms: how well the economy adjusts to the inevitable external shocks such as the Asian financial

crises of 1997-98, 9/11, or the financial crisis of 2008-09. Actually this is a theme pervading all economics

courses, and it is simply the flip side of discussions on the proper scope of government activity. For

example, consider your reaction to the plight of George who is unemployed. If you view unemployment as

'self-inflicted' because you believe there are plenty of jobs for people actively looking for work and willing

to work hard, then you probably do not support government policies to protect people from unemployment

and assume no sense of responsibility for those unfortunate enough to be unemployed. If, on the other

hand, you see George as a victim of a set of forces beyond his control – a factory at which he worked for 25

years closed its doors - then you are more likely to be willing to consider implementation of government

policies designed to protect us from the ravages of the macroeconomy. Think of macro policy as flood

insurance.

Second, in the discussions of policies and theories, time matters. In both microeconomics and

macroeconomics there are two very different time frames - the short-run where the discussion centers on

business cycles and the ability of the government to "fine-tune" the economy and dampen those cycles, and

the long-run where the focus is on economic growth and the ability of the government to "speed up" the

growth process. For example, below you have two charts. In the first, based on Angus Maddison’s data,

one shift in the balance of economic power in the world is evident. In 1500 China accounted for 25% of the

world’s GDP and was the superpower, but by 1950 the US accounted for 27% of the world’s GDP and was

the superpower. Things are changing, however, and by 2006 the rise of China had many talking about the

possibility of a second shift in the balance of world power, which created a good deal of anxiety since shifts

in the balance of power are not usually peaceful. This is a discussion of the long-run and in the unit on

economic growth we will look into what might have accounted for this shift.

In the second graph we are looking at the percent of the unemployed that have been unemployed for more

than 27 weeks. Given that it covers 60 years it is possible to discuss long run – the upward trend over that

period of time and what may have happened in the country that is responsible for the upward trend. The

data also allows us to look at the short run where the focus is on the cyclical movements where it is pretty

easy to see that the US economy follows an irregular cycle of good and bad years, although the severity of

the Great Recession stands out as “special” with nearly 50 % of the unemployed being out of work for

more than half a year. It is short run changes in data such as this that dominated the debate on the fiscal

stimulus and the Fed’s monetary policies in 2010-2011, with liberals asking for extensions of

unemployment benefits while conservatives argued for cuts in government spending.

7

Third, this course is built on the premise that history matters, the theme of Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly

Philosophers. There is an important advantage of this approach pointed out by Naomi Klein. If shocks have

an important role to play in the "selling" of economic policies, then memory is the antidote. For example, in

2012 when Romney promised the American people a massive tax cut and a balanced budget, only those

with memories knew this would not happen. We had already heard the promise before from Reagan and

Bush II, and the record clearly revealed it to be an empty promise.

There is an additional reason for the historical approach. Herbert Stein correctly noted that "[f]ashions in

economic ideas come and go, like fashions in women's clothes....the history of economic thought is closer

to the history of women's fashion than to the history of astronomy or physics,"xix so by adopting the

historical approach you can see how economics, or in this case macroeconomics, is a part of much of what

passes as history, much of what you think of as the news and as business. As we examine the evolution of

Macro Theory and Policy, we continuously emphasize the parallels between then and now because "history

is a vast early warning system."

Evolution of Macro Theory and Policy

We begin our story as the nation emerges from the Civil War, a war that demonstrated clearly the link

between economic and military power because victory went to the strongest economic power. What

followed was a story of remarkable economic growth, a time in which the US was transformed from a

rural, agricultural, eastern nation into an urban, industrial, continental giant whose modern factories

provided the edge in yet another great war - WW I. It was not all good times, though. The spectacular

growth was uneven, consisting of a series of booms and busts rather than a sustained period of growth.xx

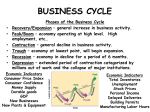

There is no simple explanation for the reoccurring business cycles, but you can think of recessions as an

economy's reaction to four "types" of shocks; (1) trade shocks originating in changes in the international

flow of goods, people, and capital, as well as trade policies, (2) external shocks such as a war in Europe, a

bad worldwide harvest, or political unrest in Argentina, (3) fiscal shocks caused by changes in the

governments' spending and taxing policies, and (4) monetary shocks associated with changes in money

supply and / or monetary policy. For those interested in some interesting background information on the

economic crises before the Great Depression, you might check out Panics, Depressions, and Economic

Crises.

The good news is these recessions were all temporary, which reinforced the prevailing view among policy

makers that they should avoid the temptation to alter the system and provide temporary relief for temporary

problems. It may be a nice idea to develop programs to help those hurt by the ravages of the business cycle,

but not if they would be ineffective or if they slowed down long-term economic growth. Basically,

Americans bought into the idea that the economy was best left to itself and there was little the government

could do to either speed up or slow growth or dampen business cycles. This is certainly one of the reasons

there was only a minimal effort to collect data on the macroeconomy. If there was nothing you could do to

improve the macroeconomy, if fiscal and monetary policy were ineffective, then why collect and

8

disseminate numbers to tell us what was already known - people were out of work and businesses were

shutting down their assembly lines and closing their doors.

As the recession following the stock market collapse of 1929 deepened and lengthened into something

never before seen - the Great Depression of the 1930s - we began to see changes in the way Americans and

elected officials viewed the economy and the government's role in managing it. The 1930s described in

John Steinbeck's classic, The Grapes of Wrath, was a special time in US history that would have a longlasting impact on the American people and their views of the proper scale and scope of government

intervention in the economy. The “specialness” is evident in the unemployment graph below. With nearly

25 percent of the nation's workers unemployed and countless thousands migrating westward, the nation was

experiencing a true economic crisis. People, millions of people, wanted change, and they got it. Major

ideological "change comes about only when social movements become so large and disruptive that

politicians can no longer ignore them,"xxiand by the early 1930s it was time to reconsider the status quo. As

Harold Laski wrote in 1932, men “accept a capitalist society … because of the material benefits it professes

to confer. Once it ceases to confer them, it cannot exercise its old magic over men's minds.”xxii

That message was not lost on Franklin Roosevelt, but he had no intention of bringing communism to

America. Rather than turning to the works of Karl Marx for guidance, Roosevelt turned to the work of John

Maynard Keynes. Where Marx would replace capitalism with a superior system, Keynes would modify

capitalism and create a kindler version. Roosevelt, with his liberal policies known as the New Deal, moved

the country toward the modern welfare state that ultimately proved to be a better choice. The US

government would now design policies to protect its people from the ravages of the economy.

This is where we begin our macroeconomic story because it is where macroeconomics began. It also marks

an important time in US economic history – it is one of only two times in US history where the country

experienced a significant ideological shift in economic theory and policy. This has happened only twice, so

you can imagine how heated the debate was at that time.

We start with the Classical Economics theory of the 1920s that provides insight into conservative policy

makers’ response to the collapse of the US economy that entailed a monetary policy of higher interest rates

to protect the gold standard and a fiscal policy of higher taxes to balance the budget. As the depression

deepened and conservative policies failed to halt the slide, there was an opening for a new perspective. Into

the theoretical and policy void stepped John Maynard Keynes peddling a liberal solution to the

macroeconomic ills - Keynesian Economics. Macroeconomic theory and policy were revolutionized from

the long-term focus on growth and minimal government involvement of conservatives to the liberals' shortterm emphasis on business cycles and government's management of the economy. Keynes' radical idea of

the multiplier that justified active fiscal and monetary policy would replace the Classical economists’

crowding out that justified a do-nothing policy.

The massive spending on World War II dragged the economy out of the 1930's Depression and diverted

people’s attention from the economy. It wasn't until 1960 when Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy beat

9

Vice-president Richard Nixon on a promise to get the economy moving that the debate resurfaced – and

where we will pick up the story again. Liberal economists who were now in positions of power in the

nation’s universities and confident that government could right the wrongs of the market system, turned

their attention to designing policies to eliminate some of the nation's major problems. When it came to

taming the business cycle and generating economic growth, the solution was the Kennedy Tax Cut. The

economy "took off" on a period of sustained growth, which is why the period is known as the zenith of

Keynesian economics. There was widespread belief that fiscal policy could manage demand to make

recessions things we read about in history books, and in the 1960s unit we will examine the theories and

policies of the 19060s. By the decade's end, however, it was clear that macroeconomic activism had its

limits. While it may have seemed a bit premature at the time, on reflection it seems as though DeLong was

correct when he wrote; "By the beginning of 1969, the US had already finished its experiment: was it

possible to have unemployment rates of four percent or below without accelerating inflation?"xxiii

The experiment had failed, but few could have anticipated what came next. In 1971 President Nixon's

announced his New Economic Policy with its incomes policies and the abandonment of the gold standard.

The efforts exerted by the US to win the war in Vietnam had created both inflation and a drain of gold, and

Nixon, who always believed he had lost the 1960 election because of the recession, was not about to

"solve" these problems by raising unemployment. The 1970's unit begins with a section on the evolution of

the international monetary system, a prerequisite for understanding Nixon's decision to abandon the gold

standard – why he did it and what was its impact. Here is where we will look carefully into the international

exchange market to understand the forces affecting the value of the US $.

Abandoning the gold standard also meant central banks around the world would now have considerable

freedom in determining their money supply. They used that freedom and in the decade “experimented”

with monetary policy as a way to get the economy growing again, which is why the second section of the

1970s unit is devoted to monetary policy. Unfortunately, the experiment went badly in a decade of

sustained and rising inflation, what Brad DeLong describes in America's Only Peacetime Inflation: The

1970s, as inevitable.

[T]he memory of the Great Depression meant that the US was highly likely to suffer an

inflationary episode like the XXXXs in the post-World war II period-maybe not as long, and

maybe not exactly when it occurred, but nevertheless a similar episode.

A graph that captures the extent of the problem is the Misery Index - the sum of inflation and

unemployment rates. It was an awful time and Americans showed their displeasure by twice voting sitting

presidents out of office – Ford and Carter. It was even worse elsewhere. All across the developed world

growth was down while inflation and unemployment were up, and Keynesians had no solution.

In Western Europe the annual growth rate in GDP per capita dropped more than a third from the rate in the

previous twenty years, while in Japan it was a drop of nearly two-thirds. It was once again a time for a

change, and that change came first in the UK where numerous labor strikes had disrupted “normal” life in

the 1970s - halting the busses, closing the mines, shutting off the power and lights, piling up the corpses. It

was also a time of humiliation as the country’s booming budget deficits and falling currency had forced it

to ask for a bailout from the International Monetary Fund. The agent of change would be little known

Margaret Thatcher, who became Prime Minister in 1979.

10

In the US the economy slipped into a "funk" that budget director David Stockman likened to an "economic

Dunkirk." Just as the high unemployment levels of the 1930s "forced" a shift to the ideological left after the

election of FDR in 1932, the simultaneous rise of inflation and unemployment that drove the misery index

up in the 1970s pushed the nation to the ideological right with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.xxiv

Whereas "'market failures' were the paramount economic concern of the 1960s and 1970s… 'government

failure' became the preoccupation of the 1980s and 1990s. Of course, communism was the greatest

'government failure' of them all, and with its failure symbolized by the tearing down of the Berlin Wall, the

believers in markets inexorably rose to take control of the 'high economic ground' on the world stage, and

in the battle of ideas."xxv

In the first section of the 1980s unit we examine Reagonomics, or what is more often referred to as Supplyside Economics, which is essentially the pre-Keynesian classical theory dressed up in newer and trendier

language. The move from demand to supply sides of the economy also redirected attention from the

economy's short-term business cycles to its long-term growth. During this decade the economics profession

refocused its efforts on unlocking the secrets to economic growth, which is the focus of the second section

in this unit.

One result of Reagan’s policies were monstrous budget deficits that dominated policy discussions in the

first half of the 1990s, just as it did in the early 2010s as the debate raged over what to do in response to the

Great recession. The 1990s unit begins with the conversion, under the direction of Fed Chairman Alan

Greenspan, of Bill Clinton the budget-busting Keynesian candidate into Bill Clinton the deficit-busting

conservative president. In the unit we will examine the government’s finances, which sets the stage for a

discussion of the debates and policies triggered by the Great Recession. For those of you who have paid

attention, you will see that we have truly come full circle. The debate that raged in the aftermath of the

Great Recession triggered by financial crisis of 2007 looks very much like the debate of the 1930s in the

Great depression. On one side we have modern Republicans / conservatives once again arguing for fiscal

austerity – substantial spending cuts to stimulate economic recovery - and for a return to the gold standard,

a monetary system they defended in the Great Depression. On the other we have Democrats / liberals

calling for quantitative easing, essentially an expansionary monetary policy of printing more money, and

the fiscal stimulus in the form of government spending increases and tax cuts.

First, however, we are going to look at some of the basics you will need to understand the evolution of

macroeconomic theory and policy.

11

12

Introduction

i

R. A. Mundell, "A Reconsideration of the Twentieth Century", June 2000 American Economic Review

Paul Scheffer, “Hitler: Phenomenon and portend,” Foreign Affairs, April 1932 in “How we got here,” Foreign Affairs

J/F 2012

iii

"1923: Loads of Money," The Economist December 31, 1999. Another quote that captures the sentiment at that time

appeared in the New York Times on October 30, 1923. 'Give me all the food an American dollar will buy,' was the order

of a prosperous looking stranger in one of the lesser restaurants in Berlin. Such lavish orders are unusual in these days

of bad exchange rates, but the waiter recovered from his astonishment and began to serve the guest. Soup, several meat

dishes, fruit and coffee were served. While the guest was smoking his cigar the waiter brought another plate of soup,

and later another meat dish. 'What does this mean?' the astonished and satisfied guest asked. The waiter bowed politely

and replied: 'The dollar has gone up again.'

iv

Unfortunately, as the table below from Thayer Watkin's site at SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY, indicates,

Germany was not the only example of hyperinflation in the pre WW II era.

Hyperinflation Rates: Pre WW II

World War I

ii

1. Germany 1920-1923

2. Russia 1921-1924

3. Austria 1921-1922

3.25 million percent

213 percent

134 percent

4. Poland 1922-1924

5. Hungary 1922-1924

World War II

275 percent

98 percent

1. Greece 1943-1944

8.55 billion percent

2. Hungary 1945-1946

4.19 quintillion percent

The post WW II era, as you can see in the table below of the more egregious examples, is also littered with examples of

hyperinflation that tended to be centered in three places - the transitional countries of the Soviet Union in the early

1990s following the collapse of communism, Latin America in the 1980s and 1990s, and Africa where many countries

were embroiled in civil wars ("The realities of modern hyperinflation"). To give you a better idea of how these buts of

hyperinflation could wreak havoc on a society, I have computed the prices of a $1 loaf of bread and a $10,000 tuition

bill after ONE year of inflation at those rates. You should have no trouble seeing the problems in a society where

tuition rates could rise from $10,000 to nearly $2,040,000 in one year and $32 trillion by your senior year.

Hyperinflation Rates: Post WW II

$1 bread a year $10,000 tuition 1

$10,000 tuition 4

Time period Peak rate %

later

year later

years later

Bolivia

1984-85 23,447

235

2,354,700 30,742,723,228,574

Brazil

1989-90

6,821

69

692,100

229,443,308,786

Peru

1990 12,378

125

1,247,800 2,424,264,071,783

Ukraine

1991-94 10,155

103

1,025,500 1,105,968,248,325

Dem. Re. of Congo

1994 23,760

239

2,386,000 32,410,203,456,016

Georgia

1994 15,606

157

1,570,600 6,085,025,078,741

Russia

1992

1,353

15

145,300

445,720,344

Turkmenistan

1993

3,102

32

320,200

10,511,998,986

Nicaragua

1998 14,315

144

1,441,500 4,317,760,877,045

v

Didi Kirsten Tatlow, “Cost of Living Increasingly a Struggle for China's Poor,” NYT 12/9/2010

Steve Hanke, Wall Street Journal, April, 28, 1999: According to Hanke, “Long before NATO struck Yugoslavia, Mr.

Milosevic’s monetary madness had destroyed the economy. Wreck an economy, then start a war: It’s an age-old power

preservation ploy.” “Yugoslavia destroyed its own economy. Mr. Milosevic claimed that the Yugoslavs were victims.

According to him, hyperinflation and resulting hardships were caused by the embargoes imposed by the United Nations

in May 1992 and April 1993. In reality Mr. Milosovic’s money machine was put into overdrive to finance his war

machine. More than 80% of all government expenditures were being financed with freshly printed dinars. As a result of

the printing of money, inflation raged for nearly two years, peaking in January of 1994 when it reached 313 million

percent a year. At that time there were in circulation 500-billion dinar notes, worth a mere 4.15 German marks when

they were printed on December 23, 1993. For the second time the world had witnessed a country turn against itself

against the backdrop of debilitating hyperinflation.

vii

Thayer Watkins at SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY, "Worst Episode of Hyperinflation in History" And do not

think this was the last of hyperinflation because in 2006 we had another example - this time in Zimbabwe. Michael

Wines, "Zimbabwe's prices rise 900%, turning staples into luxuries," New York Times May 2, 2006

vi

13

How bad is inflation in Zimbabwe? Well, consider this: at a supermarket near the center of this

tatterdemalion capital, toilet paper costs $417.

No, not per roll. Four hundred seventeen Zimbabwean dollars is the value of a single two-ply sheet. A roll

costs $145,750 -- in American currency, about 69 cents.

viii

Emily Oster, “Witchcraft, Weather, and Economic Growth in Renaissance Europe"

The situation in Argentina was so bad that within a matter of months four presidents had been forced from

office. Alberto Fujimori was a victim of the declining Peruvian economy in 2000, president Jamil Mahuad of Ecuador

was ousted in a coup led by individuals looking for an end to the country's severe recession, and in 2003 Bolivia's

president Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada fled the country in the midst of protests Bruno and Easterly (1996) suggest that

economic crises, in this case crises triggered by bouts of hyperinflation, can speed the process of economic reform in

lower income countries and that the return of growth will be faster in those countries that experienced hyperinflation. If

we follow the logic a bit further we end up where Albert Hirschman (1987) did and conclude that "inflation has acted

as the equivalent of war in eliciting change" or Alesina and Drazen (1991) who "model delayed stabilization as a war of

attrition." It should be noted, however, that not everyone agrees on the universality of the power of the macroeconomy

and its link to national security issues. Alan B. Krueger and Jitka Maleckova, in their article "Education, Poverty, and

Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection?" raise questions about the link between terrorism and poverty that is related

to the state of the economy. After an analysis of a wide array of data from around the world they concluded that there is

"little reason for optimism that a reduction in poverty or an increase in educational attainment would meaningfully

reduce international terrorism. Any connection between poverty, education, and terrorism is indirect, complicated, and

probably quite weak." Another good survey of the link between terrorism and economic activity is Abadie's "Poverty,

political freedom, and the roots of terrorism," AEA May 2006. Here the author describes the results of his effort to

explain risk of domestic terrorist attacks in which he finds that income (GDP) does not seem to matter, but political

freedom does - terrorism seems to be lower in countries with either very little or very high levels of political freedom.

There is also a link between terrorism and geography - it seems terrorism is more likely in countries where it would be

difficult to track down the terrorists - those with mountainous terrain and those with tropical jungles.

x

David Stuckler & Sanjay Basu, “How austerity kills,” NYT May 12, 2013

xi

Tara Parker-Pope, “Suicide rates rise sharply in U.S.,” NYT My 2, 2013

xii

"America's Fortunes" in 2004 State of the Union, The Atlantic Monthly J/F 2004

xiii

Jill Gloekler & Irwin L. Morris , The Effect of the U.S. Economy on Presidential Elections: 1828-2008, Paper

prepared for presentation at the American Politics Workshop, Department of Government and Politics, University of

Maryland, April 30, 2010

xiv

Larry Bartels, Inequities," New York Times Magazine, April 27, 2008

xv

One indicator is that Reagan launched his presidential campaign in Philadelphia, MS, a small southern city with a

strong link to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. At that time many southerners were angry with the federal

government for sending in federal troops, so Reagan tapped into this anger with his sattes' rights campaign. Another

element of the campaign pointed out by Krugman is that the anti tax package was designed to send the coded message

that this would starve the government of funds to help "Those People." Paul Krugman, "Bigger than Bush," NYT

January 2, 2009

xvi

Others have looked at the state of the economy and tried to link it to other indicators of well-being. In "How much

did Thailand suffer?," an article appearing in The Economist after the severe economic crash in 1998, you see that with

the onset of the crash there was an increase in the number of suicides, the children left at orphanages, babies abandoned

at hospitals, and the number of children under 14 treated for drug use. You will also learn to care about it as you head

into the 'real" world since success in your job search will hinge in part on the unemployment rate.

xvii

John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1935

xviii

It is not possible to write economic history without taking the sometimes bloody hands of twentieth-century

governments into account. First, the possibility that the secret police will knock at your door and drag you off is a

serious threat to your material well-being. Second, shooting and starvation were part of certain governments'

"management" of the economy. They were tactics used to compel the people to perform service and labor as the

government wished.

But, perhaps most important, the twentieth century is unique in that its wars, purges, massacres, and

executions have been largely the result of economic ideologies. Before the twentieth century, people

slaughtered each other over theology: eternal paradise or damnation. People slaughtered each other over

power: who gets to be top dog and command the material resources of society. Only in the twentieth century

have people killed each other on a large scale in disputes over the economic organization of society. The two

most prominent examples: the Communist governments in Russia and China, which, according to the

political scientist Rudolph Rummel, were responsible for the deaths of almost 100 million people. " DeLong

ix

xix

Herbert Stein, Presidential Economics, p 397

In the 72 years between 1857 and 1929, the US economy experienced 19 contractions (recessions) averaging 20

months, and 19 expansions averaging 25 months. The longest recession was in the 1870s and lasted 65 months - nearly

xx

14

51/2 years, while the longest expansion was 46 months - nearly 4 years during the Civil War. A partial listing of the

business cycles recorded by the National Bureau of Economic Research is presented below.

US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions

Duration in

months

Trough

Peak

Contraction

Expansion

December

1854 June

1857 -30

December

1858 October

1860

18

22

June

1861 April

1865

8

46

December

1867 June

1869

32

18

December

1870 October

1873

18

34

March

1879 March

1882

65

36

May

1885 March

1887

38

22

April

1888 July

1890

13

27

May

1891 January

1893

10

20

June

1894 December

1895

17

18

June

1897 June

1899

18

24

December

1900 September

1902

18

21

August

1904 May

1907

23

33

June

1908 January

1910

13

19

January

1912 January

1913

24

12

December

1914 August

1918

23

44

March

1919 January

1920

7

10

July

1921 May

1923

18

22

July

1924 October

1926

14

27

November

1927 August

1929

13

21

A comparison of the business cycle list with a few dates from your history courses reveals a definite pattern between

wars and business cycles. During both the Civil War (1861-1865) and WW I (1914-1918) the US economy was

growing - wars put people to work - and with the onset of peace the economy slipped into recession. This link between

government spending during wars and economic growth is testament to the power of fiscal policy, a theme that Keynes

will pick up on in the 1920s and 1930s.

During this period the US also moved in the direction of protecting its industries with tariffs, reversing a trend prior to

the Civil War. In 1861, prior to Lincoln's election, tariffs averaged 20 percent, but with the support of Eastern, and the

absence of Southern, congressmen, a series of tariff laws were passed that moved the average tariff rate higher. By

1864 the average tariff was nearly 50 percent as American industries were able to grow behind a wall of artificially

high imported products. After years in which little movement was made on tariffs, the McKinley Tariff of 1890 and the

Dingley Tariff of 1897 raised the tariff rate to 60 percent, which helped propel the economy out of the 1895-97

recession. In between the US has passed the Wilson-Gorman Act 1894 in which the sugar tariff was re-imposed, a

decision that "hammered" Cuba's new sugar industry and contributed to a political uprisings against Spain. In 1898,

after the Maine exploded in Havana's harbor, the US entered the Spanish-American War - a war that was over by the

end of the year.

What is not so obvious in the table is the link between money and the economy, but it is certainly there - a relationship

examined in greater detail in the discussion of the history of money in the 1970s. As it turns out, recessions were often

triggered by shocks to the monetary system related to international flows of gold. During these years, the US was either

on, or trying to return to the gold standard, which linked the supply of money, the supply of gold, and the international

flow of funds needed to purchase goods, services, and assets. Under this system economic or political developments in

foreign countries, discoveries of gold, or even weather changes somewhere in the world, could cause dramatic changes

in the supply of gold. For example, the western expansion in the 1880s acted as a magnate for foreign capital entering

the US. As foreigners looking to strike it rich began investing in the US, the supply of gold in the nation increased, but

by 1893 the inflows had become outflows and the US economy weathered a severe recession triggered by bank failures

and a declining money supply. Things turned around in 1896 with the discovery of new gold sources, including the

Klondike region in Alaska, and the new gold drove the money supply and prices higher.

xxi

Larissa MacFarquhar, "Outside Agitator: Naomi Klein and the New Left," The New Yorker, December 8, 2008

xxii

Harold Laski, “The position and prospects of communism,” October 11932 in “How we got here,” Foreign Affairs,

J/F 2012

xxiii

De Long "America's Only Peacetime Inflation: The 1970s"

15

xxiv

Some, such as Francis Fukuyama, thought the world had reached "The End of History" because the debates /

conflicts over the "best" economic and political systems were over, while others, such as Samuel Huntington, believed

the conflict of economic ideologies would be replaced by a new conflict, The Clash of Civilization? You would not be

too far off the mark if you looked at the US invasion of Iraq as one such clash, one that would hardly be described as

peaceful. The belief expressed by the Bush administration that American soldiers would be treated as liberators

suggests their acceptance of the end of history over the clash or civilizations view, but in 2005 we would have to say it

is "too early to call." It is also too early to call the end of communism, as you could see in the elections in Latin

America in 2005.

xxv

De Long "America's Only Peacetime Inflation: The 1970s"

16