* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Cataract surgical outcomes, visual function and quality of life in four

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

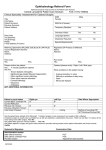

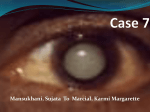

Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2011; 39: 119–125 doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02427.x Original Article ceo_2427 119..125 Cataract surgical outcomes, visual function and quality of life in four rural districts in Vietnam Leonard Yuen MD MRCOphth MPH,1 Nhu Hon Do MD PhD,2 Quoc Luong Vu MD,2 Sruti Gupta MD,3 Evelyn Ambrosio MD4 and Nathan Congdon MD MPH5 1 Singapore National Eye Centre, Singapore; 2Vietnam National Institute of Ophthalmology, Hanoi, Vietnam; 3School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, 4Helen Keller International, New York, New York, USA; and 5Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China ABSTRACT Background: To evaluate cataract surgical outcomes in four rural districts of Ha Tinh Province, Vietnam. Design: Cross-sectional study. Participants: Post-cataract surgery patients sampled randomly from facilities in four rural districts of Ha Tinh Province >3 months after surgery. Main Outcome Measures: Postoperative visual acuity (VA), visual function and quality of life. Results: Among 412 patients, the mean age was 74.5 ⫾ 9.4 years, 67% (276) were female, and 377 (91.5%) received intraocular lenses (IOL). Nearly two-thirds of patients had no postoperative visits after discharge. Postoperatively, more than 40% of eyes had presenting VA <6/18, while 20% remained <6/60. The mean self-reported visual function and quality of life for all patients were 68.7 ⫾ 23.8 and 73.8 ⫾ 21.6, respectively. Most patients (89.5%) were satisfied with surgery and the majority (94.4%) would recommend surgery to others. One-third of patients paid ⱖ$US50 for surgery. In multiple regression modelling, older age (P < 0.01), intraoperative complications (P < 0.01) and failure to receive an IOL (P < 0.01) were associated with postoperative VA <6/60. Conclusion: Satisfaction with surgery was high, and many patients were willing to pay for their operations. Poor visual outcomes were common; however, and better surgical training is needed to reduce complications and their impact on visual outcomes. More intensive postoperative follow-up may also be beneficial. Key words: cataract, epidemiology, quality of life, Vietnam, visual function. INTRODUCTION Cataract remains the leading cause of blindness in the world.1 It accounts for 65% of blindness in Vietnam2 and with an incidence of 87.6 cases per 100 000 persons annually, there are 70 870 new cases per year.3 Vietnam has a large and rapidly aging population with over 86 million people (thirteenth most populous in the world). Thus the already-significant cataract burden will only worsen without additional intervention. National cataract surgical programmes have proven able to significantly reduce the backlog of un-operated blind4 but are highly dependent on good output. In Vietnam, the cataract surgical rate was 1362 cases per million population per annum in 2006 (Personal correspondence with Dr Richard Le Mesurier, FRCS, FRCOphth, Vision 2020 Regional Coordinator for the Western Pacific Region). Although this figure is three times that of China (450 cases per million population per annum)5 it is significantly less than that of India (4425).6 䊏 Correspondence: Professor Nathan Congdon, Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510060, China. Email: [email protected] Received 16 May 2010; accepted 23 August 2010. © 2011 The Authors Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology © 2011 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists 120 Yuen et al. In order to achieve the further increases in the cataract surgical rate that will be needed to reduce the backlog of cataract blindness in Vietnam, maximizing the quality of postoperative outcomes will be critical. Previous studies have shown that cataract surgery in rural Asia may often be associated with poor visual outcomes,7–12 low visual function (VF), and reduced quality of life (QOL).7,8,11 These undesirable results are particularly striking when compared with excellent results reported from urban centres, such as in India.13,14 To date, there is little information available on visual outcomes for cataract surgery in Vietnam.15 Ha Tinh is among the poorest provinces of Vietnam with 2008 Gross Domestic Product of $US420/person/year.16 We report on postoperative vision, VF and QOL for a sample of patients undergoing extracapsular cataract extraction in Ha Tinh Province. We also report the incidence of postsurgical complications, compliance of patients with aftercare instructions, and the association of patient and surgical factors with visual outcomes. These data were collected by the Vietnam National Institute of Ophthalmology (VNIO) and an international non-governmental organization, Helen Keller International, before initiating a cataract surgical programme, and were designed to be representative of prevailing surgical outcomes at a variety of facilities in Vietnam at the time of the survey in 2003. MATERIALS AND METHODS Twenty separate institutions including tertiary government hospitals, local government facilities, local private hospitals/clinics and eye camps run by local government facilities were chosen as representative of surgical facilities in the four districts of Ha Tinh (Thi xa Ha Tinh, Thi xa Hong Linh, Huyen Nghi Xuan and Huyen Duc Tho). Random sampling from surgical lists at these facilities was used to identify 700 persons who had undergone cataract surgery in one or both eyes between January and December 2003. Among these, 412 subjects (58.9%) could be located for examination and interviews at commune health stations. These were conducted at least 3 months after the patient’s latest operation, with patients having had more recent surgery excluded. Oral informed consent was obtained for each patient, and analysis of data was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. The Declaration of Helsinki was followed throughout all study procedures. Field work was conducted by two clinical teams, each covering two of the four districts. Each team consisted of an ophthalmologist, a supervisor, a team leader and two eye health workers. The research teams underwent a 3-day didactic and practical training course conducted by the VNIO and Helen Keller International on interview, vision measurement and ocular examination techniques. Presenting visual acuity (VA) was measured for each eye of all subjects using a Tumbling E Snellen vision chart at a distance of 6 meters, with and without pinhole. A slitlamp examination, including dilation of the pupil, was performed by the team ophthalmologist to identify the presence or absence of an intraocular lens (IOL) and of surgical complications, including: posterior capsular opacification, abnormalities of wound architecture, presence of an irregular pupil, iris or vitreous adherent to the wound, de-centration of the IOL, or persistent corneal oedema. All subjects were administered questions adapted from the World Health Organization Standard Cataract Survey Form regarding the date and type of facility where the surgery was performed, the amount paid for surgery, duration of admission, the number of postoperative visits and compliance with postoperative instructions and medications. The VF and QOL interviews were conducted by one of two trained interviewers. The VF-1417 was used to assess VF, and the QOL questionnaire used in the current survey was a Vietnamese-language translation of an instrument developed for use among cataract patients in rural southern India.18 These instruments have been previously described elsewhere in detail. Briefly, the VF questionnaire consisted of 11 questions within 4 subscales: visual perception, peripheral vision, sensory adaptation and depth perception. Subjects rated their function and/or current vision problems in each of the 11 areas on a four point scale, from ‘not at all/very good’ (1) to ‘a lot/poor’ (4). The QOL questionnaire included 12 questions within 4 categories: self care, mobility, social interaction and mental well-being. Subject responses were also on a 4-point scale, with problems in each area rated as ‘none at all’ (1) to ‘a lot’ (4). For both instruments, an aggregate score of 1–100 was the created, with 1 reflecting a maximum difficulty level and 100 reflected the absence of any difficulty. Team supervisors reviewed all forms collected on a daily basis for completeness, quality of entries and consistency. The completed forms were then submitted to the VNIO Project Coordinators. Statistical methods Descriptive statistics (means, proportions, tables and graphs) were completed using SPSS Builder (SPSS © 2011 The Authors Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology © 2011 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists Cataract surgical outcomes in Vietnam Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) for age in years, gender, number of follow-up visits postoperatively, number of days in hospital and total patient cost. Presenting VA was grouped into three categories: Good (6/6–6/ 18), Borderline (<6/18–6/60) and Poor (<6/60). A cumulated logistic model was used to analyse single eye surgeries. Only the right eye was used in all analyses for patients having bilateral surgery. ChiSquared test for the proportional odds assumption was used to validate the assumption of independence for VA categories. This was not statistically significant, indicating that the categories were independent from each other (c2 test with 8 degrees of freedom = 10.8, P = 0.21). Multiple logistic regression was performed for factors that were associated with having postoperative presenting VA worse than 6/60. Covariates included older age (years), operative complications, IOL insertion, duration in hospital (days), hospital type, cost of surgery ($US), time since surgery (months), any postoperative follow-up visits and gender. The VF and QOL scores were assessed against age, gender and visual outcomes. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. RESULTS The survey collected data from 412 patients, with a mean age of 74.5 ⫾ 9.4 years and among whom 67% (276) were female. (Table 1) Surgery had been performed on a single eye in 308 (74.8%) patients, and 104 (25.2%) had undergone surgery in both eyes. The IOLs were inserted in 377 (91.5%) eyes. Only 12.6% of patients reported spending 3 or fewer days in hospital postoperatively, and the mean was 5.7 ⫾ 2.4 days (range 1 to 27 days). (Table 1) Nearly two-thirds (64.6%) of patients had no further postoperative visits after discharge from the surgical facility. (Table 1) Principal reasons included ‘felt follow-ups were unnecessary’ (n = 76, 32.7%), ‘forgot’ (n = 57, 24.6%), ‘distance or expense of travel’ (n = 56, 24.1%) and ‘not informed of need to follow up’ (n = 35, 15.1%). Surgery was performed in local government hospitals in 18.9% of cases, eye camps in 56.8% and tertiary government hospitals in 10.2%. About twothirds (64.8%) of patients reported paying <$US50 for surgery (Table 1). Median time since surgery was 24 months. Postoperatively, 44% of eyes had presenting VA better than 6/18, while 36% fell between <6/18 and 6/60, and 20% remained <6/60 after surgery. The mean self-reported VF and QOL for all patients were 68.7 ⫾ 23.8 and 73.8 ⫾ 21.6, respectively, on a scale of 0–100. (Table 1) The VA, VF and QOL outcomes were better in Vietnam than has been reported for 121 Table 1. Demographic and clinical data for 412 subjects who underwent cataract surgery in Ha Tinh, Vietnam Factor Age (years) ⱕ50 51–60 61–70 71–80 >80 Gender Male Female Hospital type Local government hospital Local private hospital / clinic Tertiary hospital Eye surgical camp Other Postoperative days in hospital ⱕ3 4 5 6 7 ⱖ8 Postoperative visits 0 1 2 ⱖ3 Total amount paid for surgery ($US) ⱕ20 21–49 50–99 ⱖ100 Data unavailable Presenting postoperative visual acuity >6/18 6/18–6/60 <6/60 Visual Function (mean ⫾ SD) Quality of life (mean ⫾ SD) Number % 7 25 81 209 90 1.7 6.1 19.7 50.7 21.8 136 276 33.0 67.0 78 39 42 234 19 18.9 9.5 10.2 56.8 4.6 52 58 125 20 134 23 12.6 14.1 30.3 4.9 32.5 5.6 266 72 53 21 64.6 17.5 12.9 5.0 166 102 124 16 4 40.3 24.8 30.1 3.9 1 182 148 82 44 36 20 68.7 ⫾ 23.8 73.8 ⫾ 21.6 SD, standard deviation. two population-based studies in rural China,7,8 but not as good as those for a clinical series from an urban centre in Southern India.14 (Table 2) Surgical complications were recorded as present at the time of follow-up examination for 14.6% (60/412) of operated eyes. (Table 3) Among 408 patients responding to the question, 365 (89.5%) were satisfied with the surgery and 385 (94.4%) would recommend surgery to others. Among those who were unsatisfied or unwilling to recommend surgery, the principal reason was poor visual outcome (79% [34/43] and 87% [20/23], respectively.) © 2011 The Authors Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology © 2011 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists 122 Yuen et al. Table 2. Surgical outcomes among 412 persons undergoing cataract surgery in Ha Tinh, Vietnam as compared to figures reported from studies in India and China Outcome Visual acuity worse than 6/60 (%) Mean visual function score Mean quality of life score Ha Tinh, Vietnam (current study) Doumen, China6 Shunyi, China7 Aravind, India13 20 68.7 ⫾ 23.8 73.8 ⫾ 21.6 52.6 41.6 ⫾ 20.0 54.5 ⫾ 29.3 44.8 61.9 ⫾ 30.0 71.0 ⫾ 31.8 1.1 79.8 ⫾ 20.0 88.5 ⫾ 20.0 Note that visual function and quality of life scores vary from 1 (worst) to 100 (best). Table 3. Surgical complications recorded at the time of follow-up examination. (Eyes may have had more than one complication: 60 subjects had any complication, and a total of 83 complications were reported) Complications Aphakia Posterior capsule opacification Uveitis Iris trauma Dislocated IOL Persistent corneal oedema Scleral erosion of the IOL Number % among 60 subjects with complications % among all 412 subjects 35 23 14 3 3 3 2 58.3% 38.3% 23.3% 5.0% 5.0% 5.0% 3.3% 8.5% 5.6% 3.4% 0.73% 0.73% 0.73% 0.49% IOL, intraocular lens. Table 4. Multiple logistic regression of factors potentially associated with having postoperative visual acuity >6/60 in 412 subjects who underwent cataract surgery in Ha Tinh, Vietnam Factor Beta value 95% confidence interval P-value Older age (years) Operative complications present Intraocular lens inserted Duration in hospital (days) Hospital type† Cost of surgery ($US) Time since surgery (months) Any postoperative follow-up visits Female gender -0.010 -0.212 0.210 0.0057 0.031 0.0001 0.00035 -0.34 0.486 -0.004, -0.016 -0.057, -0.367 0.001, 0.421 -0.239, 0.035 -0.017, 0.792 -0.001, 0.001 -0.002, 0.003 -0.488, 0.534 -0.012, 0.649 <0.01 <0.01 <0.01 0.71 0.20 0.24 0.80 0.57 0.70 Bold font indicates values significant at the <0.05 level. †Operated in tertiary government hospitals or in eye camps compared with surgeries performed in local government hospitals or local private hospitals/clinics (denominator). In multiple logistic regression modelling, increasing age (P = 0.002), intraoperative complications (P = 0.007) and failure to receive an IOL (P = 0.001) were significantly associated with presenting postoperative acuity <6/60 in the surgical eye. Gender, time since surgery, time in hospital, amount paid for surgery, having reported any follow-up visits, and the type of hospital in which the patient was operated were unassociated with poor postoperative vision (Table 4). Poor VF scores were associated with having poor vision in the operated eye (P < 0.0001), and with female gender (P = 0.03). Poor QOL scores were associated with poor vision and older age (P = 0.01) (Table 5). DISCUSSION The results of this study indicate that cataract surgical outcomes including acuity, self-reported VF and QOL for a broad variety of settings in rural Vietnam appear to be better than those reported for several locations in rural China.7,8 However, one out of five patients remained blind after surgery, a result which compares poorly with major Asian urban centres such as Aravind,14 and results recently reported for rural Asian centres emphasizing high-quality training.19 Besides self-reported VF and QOL, there are other indices of patient satisfaction that are of importance © 2011 The Authors Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology © 2011 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists Cataract surgical outcomes in Vietnam 123 Table 5. Linear regression analyses for visual function score and quality of life as associated with visual acuity in the better eye, the worse eye, age and gender Visual function score Vision in the better eye (<6/60 compared to ⱖ6/18) Vision in the worse eye (<6/60 compared to ⱖ6/18) Age Gender Quality of life score Vision in the better eye (<6/60 compared to ⱖ6/18) Vision in the worse eye (<6/60 compared to ⱖ6/18) Age Gender to cataract surgical programmes. Recent evidence suggests that positive word of mouth advertising is of particular importance in patients’ willingness to accept surgical services in rural Asia.20 In the current study, 90% of patients were not only satisfied with their own surgery, but would recommend it to others. Given the relatively high proportion of persons with poor postoperative results, the high levels of self-reported satisfaction may reflect poor preoperative vision (which we were unable to assess). It is also significant that the primary reason for not recommending surgery was failure to restore sight in the patient’s eye. Another important index of patient satisfaction for programmes dependent on surgical revenues is uptake of second eye surgery. The figure in this cohort was only 25%, as compared to greater than 50% in other rural Asian self-pay cataract surgical programmes with good outcomes.21 This is another indication that satisfaction with surgical results may not have been optimal in the current study, though the lower uptake might also be due to cost, travel distance or the lack of need for high-quality bilateral vision in this population. The results of this study have practical implications for sustainable surgical programmes in Vietnam. Patients are willing to pay substantial amounts for cataract surgery: nearly 35% paid $US50 or more, a figure consistent with the mean of $US55 reported by willingness to pay studies in rural China.22 These amounts are sufficient to cover the equipment, personnel and material costs in a surgical programme taking full advantage of economies of scale. Our results with regards to risk factors for poor visual outcomes (postoperative vision worse than 6/60 in the operated eye) suggest specific strategies for reducing the observed figure of 20% after surgery. Surgical complications, an important determinant of poor post-surgical vision in this setting, could be reduced through additional training and surgeon feedback. Training in appropriate case-selection may also improve visual results. The finding that surgical Beta value -15.93 -1.24 -0.91 -2.21 Beta value -9.51 0.02 -2.66 -1.67 95% confidence interval -12.71, 1.81, -0.82, -0.36, -19.66 -4.29 -1.00 -4.06 95% confidence interval -5.96, 3.37, -2.55, 0.37, -13.06 -3.33 -2.77 -3.71 P-value <0.001 0.22 0.36 0.03 P-value <0.001 0.22 0.01 0.09 complications are prevalent and significantly associated with vision outcome echoes results from other settings in rural Asia.8,9,23,24 The fact that failure to use an IOL is significantly associated with poor outcomes suggests that further increasing the already high (>90%) rate of pseudophakia will further reduce poor outcomes. Aphakia and failure to optimize the resulting refractive error has been identified as among the most common causes of poor postoperative vision in Asian studies.8,10,11,23,24 Strong anecdotal evidence suggests that the large majority of these patients received an average-power IOL rather than one chosen on the basis of biometry. It is likely that more widespread use of biometry will reduce poor visual outcomes in this setting. A tendency towards long inpatient stays and relatively few outpatient postoperative visits was clearly visible in our data: two-thirds of patients had no visits after discharge. Though the postoperative follow-up was not significantly associated with visual outcome in this cohort, the observational study design was subject to bias in this regard. The question remains as to whether more comprehensive follow-up might have improved outcomes. More intensive follow-up implies additional costs to both patients and hospitals. Services such as refraction21 and yttrium aluminium garnet (YAG) capsulotomy25 delivered at the time of follow-up may improve vision, though uptake in rural Asian settings may be low.21,25 Studies of scaled-back follow-up in the developed world have not generally shown a significant impact on vision,26 but these are of uncertain relevance in the developing world setting, where postoperative follow-up can offer an opportunity to identify and treat ocular comorbidities masked preoperatively by dense lens opacity.27 The results of this study must be understood within the context of its limitations. Although the sample was chosen to be representative of different venues for cataract surgery in four rural districts in Ha Tinh Province, Vietnam, it is not © 2011 The Authors Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology © 2011 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists 124 Yuen et al. population-based, as are some Asian studies of cataract surgical outcomes.7–10 The possibility of bias and failure to accurately represent the population of interest cannot be excluded. As noted above, no controlled protocol was employed for length of hospital stay or follow-up. The possibility remains that failure to observe an association between these variables and visual outcome is due to the fact that vision drove decisions about inpatient stay or follow-up, rather than the reverse. Though pinhole vision was measured, refraction and best-corrected VA were not. It may, however, be argued that presenting acuity is the most relevant visual outcome in this setting in view of the modest reported uptake of postoperative refractive services even when available in rural Asia.21 Finally, ocular comorbidities and posterior capsular opacity, potentially important and remediable cause of suboptimal postoperative visual outcomes in rural Asia25,27 were not assessed in the current study. Despite its limitations, the current report provides data on cataract surgical outcomes in one of the largest countries in Southeast Asia. These results highlight the fact that patients are generally willing to recommend surgery to others and often ready to pay substantial amounts for operations, both of which are of importance to programme planners in Vietnam. Observed risk factors for poor outcomes suggest some practical strategies to reduce the prevalence of postoperative blindness, which affected one out of five patients in this setting. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A. B. C. D. Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Starr Foundation, New York City, NY, USA. Financial disclosures: None. Contributions of authors: Design and conduct of the study (NHD, QLV); collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data (LY, NHD, QLV, EA, NC); and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript (LY, NHD, QLV, SG, EA, NC). Statement of conformity with author information: Oral informed consent was obtained for each patient, and analysis of data was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. The Declaration of Helsinki was followed throughout all study procedures. REFERENCES 1. Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya’ale D et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ 2004; 82: 844–51. 2. Orbis. Country Profile for Vietnam. Accessed October 2010. Available from: http://www.orbis.org/Default. aspx?cid=8242&lang=1&pre=view 3. World Health Organization Country Health Information Profile. Western Pacific Region Health Databank for Vietnam. 2005 revision. Accessed October 2010. Available from: http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/ user_upload/arsh/Country_Profiles/Viet_Nam/ Chapter_6.pdf (Table 38). 4. Jose R, Bachani D. World Bank-assisted cataract blindness control project. Indian J Ophthalmol 1995; 43: 35–43. 5. Tan L. Increasing the volume of cataract surgery: an experience in rural China. Community Eye Health 2006; 19: 61–3. 6. Aravind S, Haripriya A, Taranum BSS. Cataract surgery and intraocular lens manufacturing in India. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2008; 19: 60–5. Review. 7. He M, Xu J, Li S, Wu K, Munoz S, Ellwein LB. Visual acuity and quality of life in patients with cataract in Duomen County, China. Ophthalmology 1999; 106: 1609–15. 8. Zhao J, Sui R, Jia L, Fletcher A, Ellwein LB. Visual acuity and quality of life in patients with cataract in Shun Yi County, China. Am J Ophthalmol 1998; 126: 515–23. 9. Murthy GV, Ellwein LB, Gupta S, Tanikachalam K, Ray M, Dada VK. A population based eye survey of older adults in a rural district of Rajasthan: II. Outcomes of cataract surgery. Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 686–9. 10. Thurlasirij RD, Reddy A, Selvaraj S, Munoz S, Ellwein LB. The Sivaganga eye survey II. Outcomes of cataract surgery. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2002; 9: 313–24. 11. Nirmalan PK, Katz J, Robin AL et al. Utilisation of eye care services in rural south India: the Aravind Comprehensive Eye Survey. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 1237– 41. 12. Pokharel GP, Lelvaraj S, Ellwein LB. Visual Functioning and Quality of life outcomes among cataract operated and unoperated blind populations in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol 1998; 82: 606–10. 13. Mamaidipudi PR, Vasavada AR, Merchant SV, Namboodiri V, Ravilla T. Quality of Life and visual function assessment after phacoemulsification in an urban Indian population. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003; 29: 1143–51. 14. Prajna NV, Chandrakanth KS, Kim R et al. The Madurai Intraocular Lens Study. II: Clinical outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 1998; 125: 14–25. 15. Tobin S, Nguyen QD. Extracapsular cataract surgery in Vietnam: a 1 year follow-up study. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1998; 26: 13–17. 16. Wikipedia. Ha Tinh Province Information Profile. Accessed May 2010. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Ha_Tinh_Province 17. Cassard SD, Patrick DL, Damiano AM et al. Reproducibility and responsiveness of the VF-14. An index of functional impairment in patients with cataracts. Arch Ophthalmol 1995; 113: 1508–13. © 2011 The Authors Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology © 2011 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists Cataract surgical outcomes in Vietnam 18. Fletcher AE, Ellwein LB, Selvaraj S, Vijaykumar V, Rahmathullah R, Thulasiraj RD. Measurements of vision function and quality of life in patients with cataracts in southern India. Report of instrument development. Arch Ophthalmol 1997; 115: 767–74. 19. Lam DS, Congdon NG, Rao SK et al. Visual outcomes and astigmatism after sutureless, manual cataract extraction in rural China: study of cataract outcomes and up-take of services (Scouts) in the caring is hip project, report 1. Arch Ophthalmol 2007; 125: 1539–44. 20. Congdon N, Rao SK, Choi K et al. Sources of patient knowledge and financing of cataract surgery in rural China: the sanrao study of cataract outcomes and up-take of services (SCOUTS), report 6. Br J Ophthalmol 2008; 92: 604–8. 21. Congdon NG, Rao SK, Zhao X, Choi K, Lam DS. Visual function and postoperative care after cataract surgery in rural China: study of cataract outcomes and up-take of services (SCOUTS) in the caring is hip project, report 2. Arch Ophthalmol 2007; 125: 1546–52. 22. He M, Chan V, Baruwa E, Gilbert D, Frick KD, Congdon N. Willingness to pay for cataract surgery in rural southern China. Ophthalmology 2007; 114: 411– 16. 125 23. Bourne RR, Dineen BP, Ali SM et al. Outcomes of cataract surgery in Bangladesh: results from a populationbased nation-wide survey. Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87: 813–19. 24. Bourne RR, Dineen BP, Jadoon Z et al. Outcomes of cataract surgery in Pakistan: results from the Pakistan National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey. Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91: 420–6. 25. Congdon N, Fan H, Choi K et al. Impact of posterior sub-capsular opacification on vision and visual function among subjects undergoing cataract surgery in rural China: the study of cataract outcomes and uptake of services (SCOUTS) in the caring is hip project, report 5. Br J Ophthalmol 2008; 92: 598–603. 26. Tinley CG, Frost A, Hakin KN, McDermott W, Ewings P. Is visual outcome compromised when next day review is omitted after phacoemulsification surgery? A randomised control trial. Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87: 1350–5. 27. Liu Y, Congdon N, Fan H, Zhao X, Choi K, Lam DS. Ocular comorbidities among cataract-operated patients in rural China: the caring is hip study of cataract outcomes and uptake of services (SCOUTS), report No. 3. Ophthalmology 2007; 114: 47–52. © 2011 The Authors Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology © 2011 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists