* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Concepts that Revolutionized the Field of Infectious Diseases

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

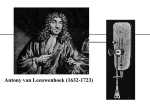

90 Journal of The Association of Physicians of India ■ Vol. 63 ■ August 2015 Pioneers in Infectious Diseases The Concepts that Revolutionized the Field of Infectious Diseases Piyush Chaudhari1, Anjali Shetty2, Rajeev Soman3 T he fields of Microbiology and Infectious diseases have developed tremendously in the 19th and the 20th centuries. Four revolutionary concepts that evolved during this period form the cornerstones on which these fields have developed further. Louis Pasteur and Germ Theory of Infectious Diseases Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization. Louis Pasteur was an average student in his early years, and not particularly academic, as his interests were fishing and sketching. He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree (1840), Bachelor of Science degree (1842) and a doctorate (1847) at the École Normale in Paris. Professionally he held several posts of importance in various universities. During these appointments he was considered a strict disciplinarian responsible for raising the standards of exams and greater competition. Pasteur often made a remark: “dans les champs de l’observation, le hasard ne favorise que les esprits préparés.” (In the field of observation, chance favors only the prepared mind) fermentation experiment and crushing the theory of spontaneous generation of life. Before Pasteur there existed the miasma theory of disease transmission (which held that diseases such as cholera, chlamydia or the Black Death were caused by a miasma, a noxious form of “bad air”) and the theory of spontaneous generation. Following his fermentation experiments, Pasteur demonstrated that the skin of grapes was the natural source of yeasts, and that sterilized grapes and grape juice n e ve r f e r m e n t e d . H e r e c e i ve d a stern criticism from Félix A r c h i m è d e P o u c h e t , w h o wa s director of the Rouen Museum of Natural History. To settle the debate between the eminent scientists, the French Academy of Sciences offered Alhumbert Prize carrying 2,500 francs to whoever could experimentally demonstrate for or against the doctrine. Pa s t e u r d e m o n s t r a t e d t h a t fermentation is caused by the growth of micro-organisms, and the emergent growth of bacteria in nutrient broths is due not to spontaneous generation, but rather to biogenesis (Omne vivum ex vivo “all life from life”). In 1856, a local wine manufacturer sought his advice on the problems of making beetroot alcohol and souring after long storage. In 1857, he developed his ideas stating that: “I intend to establish that, just as there is an alcoholic ferment, the yeast of beer, which is found everywhere that sugar is decomposed into alcohol and carbonic acid, so also there is a particular ferment, a l a c t i c ye a s t , a l wa y s p r e s e n t when sugar becomes lactic acid.” He demonstrated that yeast was responsible for fermentation to produce alcohol from sugar, a n d t h a t a i r ( o x y g e n ) wa s n o t required. And that fermentation could also produce lactic acid (due to bacterial contamination), which make wines sour. This is regarded as the foundation of Pasteur’s To prove himself correct, Pasteur exposed boiled broths to air in a swan-neck flask that contained a filter to prevent all particles from passing through to the growth medium, and even in a flask with no filt er at all, wit h ai r bei n g admitted via a long tortuous tube that would not allow dust particles to pass. Nothing grew in the broths u n l e s s t h e f l a s k s we r e b r o k e n open, showing that the living organisms that grew in such broths came from outside, as spores on dust, rather than spontaneously generated within the broth. This was one of the most important experiments disproving the theory of spont aneous g enera t i o n f o r which Pasteur won the Alhumbert Prize in 1862. He concluded that: “Never Fellow in Infectious Diseases, 2Consultant Microbiologist, 3Consultant Physician and Infectious Diseases Specialist, PD Hinduja National Hospital and MRC, Mumbai, Maharashtra 1 Journal of The Association of Physicians of India ■ Vol. 63 ■ August 2015 will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this simple experiment. There is no known circumstance in which it can be confirmed that microscopic beings came into the world without germs, without parents similar to themselves.” The germ theory of disease states that some diseases are caused by microorganisms. These small organisms, too small to see without magnification, invade humans, animals, and other living hosts. Their growth and reproduction within their hosts can cause a disease. While Pasteur was not the first to propose the germ theory (Girolamo Fracastoro, Agostino Bassi,Friedrich Henle and others had suggested it earlier, with an experimental demonstration by Francesco Redi in the 17th century). Pasteur developed it and conducted experiments that clearly indicated its correctness and managed to convince most of Europe that it was true. Today, he is often regarded as the father of germ theory. Robert Heinrich Herman Koch and his Postulates addition, Koch created and improved laboratory technologies and techniques in the field of microbiology, and made key discoveries in public health. His research led to the creation of Koch’s postulates, a series of four general principles linking specific microorganisms to specific diseases that remain today the «standard» in medical microbiology. These postulates, which not only outlined a method for linking cause and effect of an infectious disease but also established the significance of laboratory culture of infectious agents. The postulates were formulated by Robert Koch and Friedrich Loeffler in 1884, based on earlier concepts described by Jakob Henle. Koch applied the postulates to describe the etiology of cholera and tuberculosis, but they have been generalized to other diseases. The postulates are: 1. The organism must always be present, in every case of the disease. 2. The organism must be isolated from a host suffering from the disease and grown in pure culture. 3. S a m p l e s o f t h e o r g a n i s m taken from pure culture must cause the same disease when inoculated into a healthy, susceptible animal in the laboratory. 4. The organism must be isolated from the inoculated animal and must be identified as the same original organism first isolated from the originally diseased host Robert Koch (1843 – 1910) was a celebrated German physician a n d pi o n e e r i n g m ic robiologis t and is considered the founder o f mo de r n b a cteriology. H e is known for his role in identifying the specific causative agents of tuberculosis, cholera, and anthrax and for giving experimental support for the concept of infectious diseases. In Koch’s postulates have played an important role in microbiology, yet they have major limitations. For example, Koch was well aware that in the case of cholera, the causal agent, Vibrio cholerae, could be found in both sick and healthy people, invalidating his first postulate. Furthermore, viral diseases were not yet discovered when Koch formulated his postulates, and 91 there are many viruses that do not cause illness in all infected individuals, a requirement of the first postulate. Additionally, it was known through experimentation that H. pylori caused mild inflammation of the gastric lining when ingested. It still did not immediately convince skeptics that H. pylori was associated with ulcers. Eventually, skeptics were silenced when a newly developed antibiotic treatment eliminated the bacteria and ultimately cured the disease. More recently, modern nucleic acid-based microbial d e t e c t i o n m e t h o d s h a ve m a d e Koch’s original postulates even less relevant. These nucleic acidbased methods make it possible to identify microbes that are a ssoci at e d wi t h a d i se a se , b u t in many cases the microbes are uncultivable. Also, nucleic acidbased detection methods are very sensitive, and they can often detect t h e ve r y l o w l e ve l s o f v i r u s e s that are found in healthy people without disease. K o c h ’ s p o s t u l a t e s h a ve a l s o influenced scientists who examine microbial pathogenesis from a molecular point of view. In the 1980s, a molecular version of Koch’s postulates was developed to guide the identification of microbial genes encoding virulence factors. Molecular Koch’s postulates are a set of experimental criteria that must be satisfied to show that a gene found in a pathogenic microorganism encodes a product that contributes to the disease caused by the pathogen. The postulates were formulated by the microbiologist Stanley Falkow in 1988 and are based on Koch’s postulates. For many pathogenic microorganisms, it is not currently possible to apply molecular Koch’s postulates to a gene in question. Paul Ehrlich and the Magic Bullet Paul Ehrlich (1854 – 1915) was a German Jewish physician and 92 Journal of The Association of Physicians of India ■ Vol. 63 ■ August 2015 was a Russian biologist, zoologist and protozoologist, best known for his pioneering research into the immune system. scientist who worked in the fields of hematology, immunology, and chemotherapy. His laboratory discovered arsphenamine ( S a l va r s a n ) , t h e f i r s t e f f e c t i ve medicinal treatment for syphilis, thereby initiating and also naming the concept of chemotherapy. Ehrlich popularized the concept of a “magic bullet”. Ehrlich had postulated that if a compound could be made that se l e cti ve l y t a r g e t ed a diseasecausing organism, then a toxin for that organism could be delivered along with the agent of selectivity. Hence, a “magic bullet” (magische Kugel, his term for an ideal therapeutic agent) would be created that killed only the organism targeted. The concept of a “magic bullet” was to some extent realized by the invention of monoclonal antibodies as they provide a very specific binding affinity. Elie Metchnikoff and Phagocytosis Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (also seen as Élie Metchnikoff) (1845 –1916) Mechnikov was born in the village Ivanovka near Kharkov, Russian Empire (now near Kharkiv in Ukraine) the youngest son of Ilya Mechnikov, a Guards officer. As a child Mechnikov developed a passion for natural history as well as biology and botany. He w o u l d g i ve l e c t u r e s o n t h e s e s subjects to his siblings and other small children. When Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species was published, Mechnikov became interested in the survival of the fittest, testing and teaching it. He attended Kharkiv University where he studied natural sciences, completing his four-year degree in two years. He then went to Germany to study marine fauna on the small North Sea island of Heligoland and then at the University of Giessen, University of Göttingen and then at Munich Academy. While at Giessen, he discovered, in 1865, intracellular digestion in one of the flatworms, a n o b s e r va t i o n w h i c h wa s t o influence his later discoveries. M e t c h n i k o v a l s o d e ve l o p e d a theory that aging is caused by toxic bacteria in the gut and that lactic acid could prolong life. Based on this theory, he drank sour milk every day. He wrote three books: Immunity in Infectious Diseases, The Nature of Man, and The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies, the last of which, along with Metchnikoff’s studies into the potential life-lengthening properties of lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus), inspired Japanese scientist Minoru Shirota to begin investigating a causal relationship between bacteria and good intestinal health, which eventually led to the worldwide marketing of kefir and other fermented milk drinks, or probiotics. References 1. Seckbach, Joseph (editor) (2004). Origins: Genesis, Evolution and Diversity of Life. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 20. ISBN 978-14020-1813-8. 2. Ullmann, Agnes (August 2007). “PasteurKoch: Distinctive Ways of Thinking about Infectious Diseases”. Microbe (American Society for Microbiology) 2 (8): 383–7. Retrieved December 12, 2007. He discovered phag ocy t osis after experimenting on the larvae of starfish. He realized that the process of digestion in microorganisms was essentially the same as that carried out by white blood cells. His theory, that certain white blood cells could engulf and destroy harmful bodies such as bacteria, met with scepticism from leading specialists including Louis Pasteur, Behring and others. At the time most bacteriologists believed that white blood cells ingested pathogens and then spread them further through the body. 3. Magner, Lois N. (2002). History of the Life Sciences (3 ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0-2039-1100-6. 4. Roll-Hansen, Nils. “Experimental Method and Spontaneous Generation: The Controversy between Pasteur and Pouchet, 1859–64”. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 1979; XXXIV (3): 273–292. 5. Farley J; Geison GL (1974). “Science, politics and spontaneous generation in nineteenth-century France: the PasteurPouchet debate”. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 48 (2): 161–98. PMID 4617616. 7. Amsterdamska, Olga. “Bacteriology, Historical.” International Encyclopedia of Public Health. 2008. Web. Mechnikov’s work on phagocytes won him the Nobel Prize in 1908. He worked with Émile Roux on calomel, an ointment to prevent people from contracting syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease. 8. Karnovsky ML. “Metchnikoff in Messina: a century of studies on phagocytosis”. N Engl J Med (US) 1981; 304:1178-80. 6.http://en.wikipedia.org