* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Soup as a Weight Management Strategy

Gastric bypass surgery wikipedia , lookup

Cigarette smoking for weight loss wikipedia , lookup

Overeaters Anonymous wikipedia , lookup

Obesity and the environment wikipedia , lookup

Diet-induced obesity model wikipedia , lookup

Calorie restriction wikipedia , lookup

Human nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Childhood obesity in Australia wikipedia , lookup

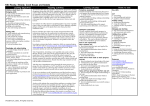

as a Weight Management Strategy www.campbellsoup.com A Comprehensive Research Review 2nd Edition, Revised December 2010 as a Weight Management Strategy A Comprehensive Research Review, December 2010 Introduction Energy Density and Calorie Intake Energy Density: A Better Way to Control Calories Combined Effects of Energy Density and Portion Size 1 1 3 4 Energy Density: Weight or Volume 5 Energy Density and Body Weight 5 Soup and Weight Management 6 Soup and Satisfaction Energy Density, Soup and Diet Quality 7 9 Conclusion 10 Putting It Into Practice 11 References 12 Soup as a Weight Management Strategy As North Americans’ waistlines continue to expand, so have the number of strategies to help people manage their weight. One approach that has been gaining steam in recent years focuses on energy density. Energy density refers to the amount of calories in a given weight of food – or specifically the number of calories per gram. A food that is high in energy density (or calorie density) provides a large amount of calories for a given weight of food, while a food of low calorie density has fewer calories for the same weight of food. With foods of lower calorie density, you can eat a larger portion for the same calories. Studies on food intake and energy density show that people tend to eat about the same weight or volume of food each day. So, including foods with a low energy density, like water-rich vegetables, helps to lower calorie intake without reducing the amount consumed – an important factor that can help you feel satisfied on fewer calories. Soup is one example of a low energy-dense, high-volume food that may be valuable in helping to e role of soup in weight management has been studied is paper summarizes the current scientific evidence that suggests soup can be an effective – and nourishing – part of a weight-management plan. Four Ways Soup Can Help Manage Body Weight: 1. Decrease hunger 2. Increase fullness 3. Enhance satisfaction 4. Reduce calorie intake Energy Density and Calorie Intake Feeling full on fewer calories is the concept behind the energy density approach. Foods that are high in water – such as fruits, vegetables and soups – are considered high-volume foods that are low in energy density. Numerous studies indicate that the energy density of foods affects calorie intake, satiety and ultimately body weight. (Rolls BJ , Bell EA, Medical Clinics 2000, Yao M, Roberts SB, Nutrition Reviews 2001, Kral TVE, Roe LS, Rolls BJ, AJCN 2004). 1 In a review of the literature, Drewnowski and colleagues concluded that energy density of the diet has a larger and more robust impact on calorie intake than any one macronutrient. (Drewnowski, Nutrition Reviews 2004). A literature review by Yao and Roberts found that in studies lasting longer than 6 months, weight loss was 3 times greater in people who ate foods of low energy density than in those who simply ate low-fat foods. (Yao M, Roberts SB, Nutrition Reviews 2001). Energy Density Energy density is the relationship of calories to the weight of food (calories per gram) Very Low Energy-Dense Foods 0 to 0.6 calories per gram. Broth-based soups, nonstarchy vegetables and fruits, milk Low Energy-Dense Foods 0.6 to 1.5 calories per gram Cereal and milk, starchy vegetables and fruits, beans, chili, yogurt Medium Energy-Dense Foods 1.5 to 4 calories per gram Bread, meats, cheeses, pizza, French fries, salad dressings, ice cream ,cake High Energy-Dense Foods 4 to 9 calories per gram Bacon, butter, oils, nuts, chips, chocolate candy, cookies Adapted from e Volumetrics Eating Plan by Barbara Rolls, PhD. Given a fixed number of calories, people who choose low energy-dense foods can “put more on their plate” for fewer calories than those who eat high energy-dense items. An analysis of food consumption patterns of more than 7,300 U.S. adults found that women and men who ate a low energy-dense diet consumed, respectively, 300 and 400 more grams of food than those who ate high energy-dense diets. (Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, AJCN 2006). Despite eating a greater weight of food, men who had low energy-dense diets ate 432 fewer calories a day than men with a high energy-dense diet. For women, the difference was 278 calories less. On average, the women who ate low energy-dense diets also had a lower body e prevalence of obesity was 6 percent lower for men and 5 percent lower for women in the low energy-dense versus high energy-dense diet groups. Lowering the energy density of entrees by adding more water and water-rich vegetables reduced calorie intake without affecting ratings of hunger and fullness. (Bell EA, Castellanos VH, AJCN 1998). In this study of normal-weight women, the researchers formulated lunch and dinner entrees with three levels of energy density. Low energy-dense entrees had a higher water content achieved primarily by adding extra vegetables, while the high energye women tended to eat the same us, the reduction in energy density resulted in a comparable reduction in calorie intake. For example, comparing the A Comprehensive Research Review - 2nd Edition, Revised December 2010 lowest, to highest energy-dense conditions, lowering the energy density by 30 percent caused participants to consume 30 percent fewer calories, despite reporting similar ratings of fullness. Other studies have shown that low energy-dense diets can reduce calorie intake 15 to 30 percent compared to high energy-dense diets. (Bell EA, Rolls BJ, AJCN 2001, Rolls BJ, Bell EA, AJCN 1999, Kral TVE, Roe LS, Rolls BJ, Appetite 2002, Ello-Martin JA, Roe LS, AJCN 2007). Furthermore, reducing the energy density did not result in differences in hunger or fullness. At the same calorie levels, foods with low energy density provide a greater volume of food, which may help people feel full at a meal while consuming fewer calories. Energy Density: A Better Way to Control Calories Fat increases the energy density of a food more than carbohydrate or protein, while water decreases energy density by adding weight but not calories. However, studies indicate that lowering the energy density of foods by increasing water content may have a greater effect on calorie intake than cutting fat. (Yao M, Roberts SB, Nutrition Reviews 2001). Research also suggests that the energy density of a food is a stronger determinant of overall calorie intake than the fat content of a food. (Rolls BJ, Bell EA, Castellanos VH, AJCN 1999). In a study by Rolls and colleagues at the Pennsylvania State University, the fat and energy density of one-half of participants’ meals was varied. For the other half, participants could choose from a variety of foods to consume until they felt satisfied. When the fat content was held constant, lowering the energy density by 30 percent significantly reduced calorie intake during meals for both lean and obese subjects. When the energy density was held constant, lowering the fat content from 37 percent to about 16 percent of calories had no effect on food intake. (Rolls BJ, Bell EA, Castellanos VH, AJCN 1999). In a recent longitudinal study, women consuming lower energy density diets reported eating more food but significantly less total calories than those eating a higher energy density diet. The authors concluded that lower energy density diet can be achieved by consuming more servings of fruits and vegetables and limiting intake of high fat foods and such diet moderates weight gain (Savage JS, Marini M, Birch LL, AJCN 2008). Several other studies have also examined the impact of fat on satiety and provide consistent evidence that manipulating the amount of fat in the diet does not infl uence food intake when the energy density of the diet is held constant. (Rolls BJ, Bell EA, EJCN 1999, The secret to feeling full? Reducing the energy density of foods is more effective than reducing fat when controlling calories. 3 Duncan KH, Bacon JA, Weinsier RL, AJCN 1983, Rolls BJ, Kim-Harris S, Fischman MW, AJCN 1994, Rolls BJ, J Nutr 2000). There is also evidence that people who are obese or considered “restrained” eaters (chronically limit their eating behavior to prevent weight gain), may be less apt to feel what little satiety effect fat has. (Mattes R, Physiology & Behavior 2005, Cecil JE, Francis J, Physiology & Behavior 1999, Prentice A, AJCN 1998). Regardless of the fat, carbohydrate and protein content of the diet, when the palatability of foods is similar, it appears that the energy density of a food is the major determining factor in how foods affect satiety and calorie intake. (Rolls BJ, J Nutr 2000). Ello-Martin and colleagues at the Pennsylvania State University compared two approaches for reducing the energy density of a weight-loss diet. (Ello-Martin JA, Roe LS, AJCN 2007). In this study, one group of obese women was instructed to reduce fat intake and the other was taught to cut fat and increase consumption of water-rich foods such as fruits and vegetables. During the first six months of the study, the lower-fat, fruit and vegetable group lost 33 percent more weight than the group that concentrated solely on cutting fat. After one year of intervention, 49 percent of the subjects in the lower-fat, fruit and vegetable group were no longer considered obese, whereas 28 percent of those in the lower-fat only group achieved this classification. Fat intake did not differ significantly between the two groups. What differed was the volume of food consumed. Those in the lower-fat, fruit and vegetable group consumed a 25 percent greater weight of food. During the intervention, hunger ratings for the lower-fat only group did not differ compared to when they started the study. Women in the lower-fat, fruits and vegetables group; however, reported lower hunger ratings compared to baseline and lower hunger ratings compared to the lower-fat only group. The energy density of food, therefore, was an important factor in reducing calorie intake, enhancing weight loss and controlling hunger. Because dieting is often associated with hunger and deprivation, this study suggests that choosing low energy-dense, high-volume foods can be an effective weight-loss strategy. It can provide a satisfying amount of food, provide a variety of flavorful foods, and enhance satiation. And, it can do all of that for fewer calories and a net weight loss. Combined Effects of Energy Density and Portion Size Similar to fat consumption, portion size has been implicated as a factor contributing to the increased incidence of obesity in North America. Large portion sizes increase calorie intake. (Ledikwe JH, Ello-Martin JA, Rolls BJ, J Nutr 2005, Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS, AJCN 2006). Researchers have shown that increasing portion size and energy density of a single food has additive effects leading to increased calorie intake during a meal. (Kral, Roe, Rolls, AJCN 2004). It appears the counter equation holds true as well – reducing portion size and energy density has additive effects for lowering calorie intake. In one study, the portion size and energy density of multiple foods was manipulated and served to participants over a two-day period. (Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS, AJCN 2006). Reducing the energy density of foods by 30 percent resulted in a 23 percent decrease in calorie intake for the day. Reducing portion size by 25 percent led to a 12 percent decrease in calorie intake. Combined, their influence yielded a 32 percent decrease in energy intake A Comprehensive Research Review - 2nd Edition, Revised December 2010 Energy Density: Weight or Volume? The water content of foods is a critical determinant of energy density and appears to have a larger effect than other ingredients, such as fat or fiber. (Yao M, Roberts SB, Nutrition Reviews 2001, Rolls BJ, Drewnowski A, Ledikwe JH, JADA 2005). Soup, fruits and vegetables contain about 80-95 percent water. Water is calorie-free. Thus, it adds weight and volume – factors that have been shown to enhance fullness. Interestingly, the positive effect of the volume of food on satiety is not always dependent on increasing the weight of food. Rolls and colleagues created a greater volume of milkshake by adding air. (Rolls BJ, Bell EA, Waugh BA, AJCN 2000). The men in the study were given a yogurt-based milkshake 30 minutes before lunch. The milkshakes varied in volume (300 ml, 450 ml, 600 ml) but were equal in calories and weight because the higher volume was achieved by incorporating air. The study participants ate 12 percent fewer calories at lunch after they drank the 600 ml milkshake and reported greater increases in feelings of fullness. Similar studies that used water to increase volume and lower energy density of a pre-meal drink found water had a greater impact on satiety and reduced calorie intake more than the addition of air — perhaps because of the greater weight of water. Energy Density and Body Weight Energy density has been shown to be an important determinant of body weight status in clinical and population studies (Ello-Martin JA, Roe LS, Ledikwe JH, Beach AM, Rolls BJ, AJCN 2007, Ledikwe JH, Rolls BJ, Smiciklas-Wright H, Mitchell DC, Ard JD, Champagne C, Karanja N, Lin PH, Stevens VJ, Appel LJ, AJCN 2007, Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Beach AM, Kris-Etherton PM, Obesity Research 2005, Mendoza JA, Drewnowski A, Christakis DA, Diabetes Care 2007, Kant AK, Graubard BI. Int J Obesity (Lond) 2005, Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Khan L, Serdula MK, Seymour JD, Tohill BC, Rolls BJ, AJCN 2006; Bes-Rastrollo M, van Dam R, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Li TY, Sampson LL and Hu, AJCN 2008). In a clinical study, reduction in dietary energy density was found to be the main predictor of weight loss during first two months among 200 overweight men and women (Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Beach AM, Kris-Etherton PM, Obes Res 2005). Changes in dietary energy density were also related to changes in body weight in a secondary analysis of the results from a multicenter intervention (Ledikwe JH, Rolls BJ, Smiciklas-Wright H, Mitchell DC, Ard JD, Champagne C, Karanja N, Lin PH, Stevens VJ, Appel LJ, AJCN 2007). In a prospective study of over 50,000 middle aged women, the dietary energy density was associated with weight gained over a eight year period (Bes-Rastrollo M, van Dam R, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Li TY, Sampson LL and Hu, AJCN 2008). In a crosssectional study analyzing NHANES 1999-2002, dietary energy density was independently and significantly associated with higher BMI among 9,688 U.S. adults (Mendoza JA, Drewnowski A, Christakis DA, Diabetes Care 2007). Barbara Rolls recently summarized that several clinical trials have shown that reducing energy density of the diet by the addition of water rich foods such as fruits and vegetables was associated with substantial weight loss even when patients were not told to restrict calories and lowering energy density could provide effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of obesity (Rolls BJ, Physiol Behav 2009) 5 Soup and Weight Management As a water-rich food, soup has been shown to help control hunger, reduce total calorie intake and offer eating satisfaction – all key factors to successful weight management. (Duncan KH, Bacon JA, AJCN 1983, Kissileff HR, Thornton J, Physiology & Behavior 1982, Rolls BJ, Federoff IC, Gurthrie JF, Appetite 1990, Himaya A, Louis-Sylvestre J, Appetite 1998, Rolls BJ, Roe LA, Beach AM, Obesity Research 2005, Flood JE, Rolls BJ, Appetite 2007). Studies indicate that soup has a high satiety value and may help people feel full and eat less at a meal when served as a first course. (Mattes R, Physiology & Behavior 2005). In a series of experiments to evaluate the satiety effects of various foods, Kissileff and colleagues found that the soups they tested as a first course or “preloads” were significantly more satiating than the crackers and cheese or juice that were served as preloads. When the women ate soup before their meal, they consumed fewer calories at that meal and reported a decreased desire to eat. (Kissileff HR, Gruss LP, Thornton J, Physiology & Behavior 1984). Why Soup May Help You Eat Less Low energy density (fewer calories per gram than other foods) High volume, so dieters feel less deprived with fewer calories Strong sensory cues (taste, flavor and texture) Cognition cues (meal more satisfying than sipping a beverage) Rolls and colleagues studied the satiety effects of eating soup as a first course in normal weight, non-dieting men. (Rolls BJ, Fedoroff IC, Gurthrie JF, Appetite 1990). When subjects ate tomato soup as their first course, they consumed an average of 100 fewer calories in the meal than when they ate either cheese and crackers or cantaloupe as their first course. Men also reported a significant decrease in hunger and an increased feeling of fullness after consuming the soup. Soup was found to be significantly more satiating than cheese and crackers or the melon (that had an energy density similar to the soup). Water served within a soup appears to be significantly more satiating compared to water orwart ML AJCN 1999). In this study by Rolls and colleagues, 24 normal-weight women ate breakfast, lunch and dinner in the laboratory one day a week for four weeks. Before each lunch, they received a preload meal of a chicken, rice and vegetable casserole, a chicken, rice and vegetable casserole with a glass of water or a chicken, rice vegetable soup e serving size was 1 ½ cups for the casserole and 2 ½ cups for the soup. When women ate the soup, they consumed 16 percent fewer calories than when they ate either the casserole alone or the casserole with the glass of water. Eating the soup significantly increased feelings of fullness and reduced hunger. Drinking a glass of water with the casserole had no effect on total calories consumed or on feelings of being full. us, water was found to have a greater impact on satiety and calorie intake when it was e researchers believe part of A Comprehensive Research Review - 2nd Edition, Revised December 2010 Satiety is enhanced when water is incorporated into a food, such as soup, but not when consumed as a beverage. the reason may be related to volume, which might have caused more stomach distension, or that the soup itself dispersed nutrients in the stomach and intestine more than the solid meals did and this dispersion delayed stomach emptying or relayed signals to the body that ey suggest it’s also possible that drinking beverages causes the body to respond to thirst mechanisms whereas eating soup yields a satiety-related response. Consuming soup on a regular basis was found to help bolster satiety during weight loss in e Pennsylvania State University. (Kris-Etherton PM, Ledikwe JM, Roe LM, FASEB Journal 2004). In this study of overweight and obese men and women, the researchers found that adding one or two servings of soup per day to a weight-loss plan, increased participants’ ratings of fullness. Furthermore, despite losing the same amount of weight, about 15 pounds over one year, participants who were given soup to consume twice per day, ate a greater weight of food than participants in the comparison group, who were not given soup to eat. Participants in a fourth group, given energy-dense, dry snacks to consume twice per day, reported the greatest hunger and lost the least amount of weight (about 10 pounds). Taken together, these results suggest that soup helps enhance fullness when calorie intake is reduced. Water in foods increases volume, reduces energy density and promotes a feeling of fullness. Fruits, vegetables and soups contain 80 to 95 percent water. Soup and Satisfaction Soup has been shown to have a high satiety value (Mattes R, Physiology & Behavior 2005) and people perceive soup to be filling and satisfying – which adds to the perception that it is satiating. (Rolls BJ, Fedoroff IC, Guthrie JF, Appetite 1990). Mattes at Purdue University documented the satisfying nature of soup by comparing the satiety values of liquids, solids and soups. (Mattes R, Physiology & Behavior 2005). Study participants rated hunger and fullness after consuming various preloads: apple juice, apple or apple soup; chicken breast or chicken soup; and peanuts or peanut soup. e soup preload meals led to higher satiety ratings in contrast to the liquids and solid food options. Calorie intake was lower on the days soup was consumed than on the days solid e author concluded that liquids have minimal satiety properties, yet the opposite effect holds true for soups. In terms of the influence on appetite, soups were more comparable to solid foods than liquids. 7 Several characteristics of soup have been suggested to be involved in enhancing satiety, including the amount consumed, energy density and temperature. (Kissileff HR, Gruss orton J, Physiology & Behavior 1984, Norton GNM, Anderson AS, Hetherington e type of soup may not be a significant factor. In a study funded by the National Institutes of Health, four different soups were evaluated as a preload: broth and vegetables served separately, chunky vegetable soup, chunky-pureed vegetable soup or pureed vegetable soup. (Flood JE, Rolls BJ, Appetite 2007). When soup was consumed as a first course or preload, the study participants reduced calorie intake at e type of soup did not significantly affect calorie intake or ratings of satiety. Sipping a bowl of soup often takes longer to eat compared to eating solid foods, which may e provide additional satiating effects. ( Jordan HA, Levitz LS, Utgoff physiological feedback from ingested food takes at least 20 minutes to develop, independent of the amount of food eaten. Researchers examined the impact of eating soup on calorie intake and rate of eating and found that men and women who ate soup for lunch or dinner consumed fewer calories in the same meal and ate at a slower rate. A more recent study by Andrade and colleagues showed that when healthy women ate a meal quickly (~ 9 minutes) versus more slowly (>20 minutes), they reported lower satiety ey also consumed nearly 70 calories more at the fast-paced meal than at the more leisurely one. To maximize the satiating or hunger-reducing effects of soup, researchers at Columbia University in New York tested whether hunger ratings would be lower with a larger portion of soup eaten before a meal versus a smaller portion. (Muurahainen NE, Kissileff HR, AJP 1991, Nolan LJ, Guss JL, Liddle RA, Nutrition 2003). Hunger ratings were significantly reduced after men in the study ate nearly 18 ounces of tomato soup compared e researchers studied the effect of soup in combination with treatments ey concluded that hunger ratings are more sensitive predictors of intake when the stomach is relatively full (after the larger soup serving) than when it is relatively empty (after the smaller soup serving). Eating a big bowl of soup caused the body to release more CCK, which helped trigger a feeling of fullness. Soup is a well-accepted food and can be a welcome addition to any weight-management plan. Researchers confirmed these observations when subjects who ate soup every day on a reduced-calorie diet said they liked a soup strategy better than simply reducing calories. A Comprehensive Research Review - 2nd Edition, Revised December 2010 According to a self-administered questionnaire designed to evaluate participants’ perceptions regarding their eating plans, 97 percent of the soup group members were enthusiastic about the value of soup in their weight-loss plans. (Foreyt JP, Reeves RS, Darnell LS, JADA 1986). Energy Density, Soup and Diet Quality Including more water-rich foods – such as fruits, vegetables and soups – is one of the most effective strategies for lowering the energy density of the diet. Studies indicate that incorporating more of these water-containing foods can also enhance the overall quality of the diet. People who eat a low energy-dense diet tend to eat more fruits and vegetables and more fiber, and have diets that contain more vitamin A, C and folate. (Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Khan L, JADA 2006). It has also been observed that the energy density and nutrient density of foods and diets is inversely related. (Rolls BJ, Drewnowksi A, JADA 2005). A low energy-dense diet that is rich in fruits and vegetables may help lower the risk of heart e Pennsylvania State University showed that women in the group instructed to reduce fat intake and increase intake of fruits and vegetables, as part of the weight-loss diet, had more beneficial changes in blood levels of insulin, triglycerides and non-HDL cholesterol than women instructed to reduce fat intake only during weight loss. (Ello-Martin JA, Roe LS, Ledikwe JH, AJCN 2007). French researchers examined soup consumption and nutrient intake. (Galan P, Renault N, Aissa M, IJVNR 2003). Subjects who consumed soup on a daily basis had lower intakes of e researchers conclude that soup helped increase vegetable consumption, which in turn increased vitamin intake. In a French study, eating soup was associated with better diet quality and lower body weight. Two studies conducted at the University of Delaware compared the diets of soup users and non-soup users based on an analysis of national food consumption surveys. (Hartell B, Khoo CS, Gaughan C, FASEB J 2003, Khoo CS, Hartell B, Montgomery P, FASEB J 2003). Researchers found that on the days when people ate soup, the composition of their diet was more consistent with the Dietary Guidelines than on days when people did not e diets of soup users (1/2 to 3 cups of soup per day) contained more whole grains, dark green and dark yellow vegetables, fruit, fish, beans and fiber than non-soup 9 e diets of soup users also contained fewer calories, less fat and saturated fat, less cholesterol and added sugars. Other researchers have found that frequent soup users consume less fat and are more likely to have a lower body mass index compared to non-soup and occasional soup users. (Bertrais S, Galan P, Bertrais S, JHND 2001). Frequent soup users were defined as people who ate 5-6 servings of soup in a 6-day period. Conclusion Reducing the energy density of the diet may be an effective strategy to achieve and maintain a healthy weight. One of the easiest ways to reduce the energy density of the diet is to eat more waterrich foods, such as fruits, vegetables and soups. Soup is a nourishing and satisfying food that can help people feel full on fewer calories. Eating more soup can be a convenient way to accomplish several health-promoting goals. It helps lower the energy density of the diet, it is an easy way to eat more vegetables, it is simple and quick to prepare, and it can help add variety to the diet. e convenient nature of soup makes it a great kitchen staple. Because of its multi-faceted nature, i.e. sweet or savoury; creamy or broth–based; chunky or pureed, it is hard to tire of soup. There are literally dozens of varieties to choose from, including many that are lower in sodium. An additional advantage of soup is that people enjoy it in their diet, suggesting that the long-term compliance needed to achieve sustainable weight loss may be more readily accomplished when soup Putting it into practice As an appetizer:Whether eating at home or eating out, soup is a smart start. To reap its satiating benefits when eating out, order soup first. Enjoy it, then order the balance of your meal from the menu. Chances are you’ll order less. When eating at home, dish up a bowl of soup. Eat it, clear the dishes, then serve the main meal. Again, it is likely your appetite for the meal that follows will be less – perhaps reducing calorie intake as much as 30 percent. As the main event: A hearty soup filled with beans, vegetables, poultry, meat or even fish can easily serve as a main entrée for lunch or dinner. Ingredient options are nearly endless for soups, so the possible varieties are broad and deep. Soup can also be the main dish or supporting cast to a sandwich or salad. As a snack: Whether it is the mid-morning or mid-afternoon munchies, the before sports energy booster or the after school pick-me-up, soup can satisfy hunger between meals. Soups that are shelf-stable and portable make them easy to eat at work, at school and on the go. As an ingredient:Broth can add volume and flavor to foods, lower their energy density ey can be used in stews, casseroles and stir fries to add ey can thin sauces and gravies and they serve as an excellent substitute for oil when sautéing meats and vegetables. As a party manager:Often cocktail parties, potlucks and picnics offer endless amounts of higher-calorie and energy-dense foods. Eating a bowl of soup before going to such events can help reduce calorie intake by satisfying one’s appetite and providing a sense of fullness. is incorporated into meals. Utilizing soup as part of a low energy-density approach to eating well can be a satiating, enjoyable and effective strategy for weight management. A Comprehensive Research Review - 2nd Edition, Revised December 2010 11 References Andrade AM, Greene GW, Melanson KJ. Eating slowly led to decreases in energy intake within meals in healthy women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108:11861191. orwart ML, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake in normal-weight women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1998;67:412-420. Bell EA, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake across multiple levels of fat content in lean and obese women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2001;73:10101018. Bertrais S, Galan P, Renault N, Zarebska M, Presiosi P, Hercbery C. Consumption of soup and nutritional intake in French adults: consequences for nutritional status. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2001;14:121-128. Bes-Rastrollo M, van Dam R, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Li TY, Sampson LL and Hu FB. Prospective study of dietary energy density and weight gain in women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008; 88:769–777. Cecil JE, Francis J, Read NW. Comparison of the effects of a high-fat and high-carbohydrate soup delivered orally and intragastrically on gastric emptying, appetite and eating behavior. Physiology and Behavior. 1999;67:299-306. Drewnowski A. Energy density, palatability and satiety: implications for weight control. Nutrition Reviews. 1999;56:347-353. Duncan KH, Bacon JA, Weinsier RL. e effects of high and low energy density diets on satiety, energy intake, and eating time of obese and non-obese subjects. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1983;37:763-767. Ello-Martin JA, Roe LS, Ledikwe JH, Beach AM, Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density in the treatment of obesity: a year-long trial comparing 2 weight-loss diets. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85:1465-1477. Flood JE, Rolls, BJ. Soup preloads in a variety of forms reduce meal energy intake. Appetite. 2007; 49:626-634. Foreyt JP, Reeves RS, Darnell LS, Wohlleb JC, Grotto AM. Soup consumption as a behavioral weight loss strategy. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1986; 86:524526. Galan P, Renault N, Aissa M, Adad HA, Rahim B, Potier de Courcy G, Hercberg S. Relationship between soup consumption, folate, beta-carotene and vitamin C status in a French adult population. International Journal of Vitamin Nutrition Research. 2003;73:315321. Hartell B, Khoo CS, Gaughan C, Montgomery P, Smith JL. Comparison of food guide pyramid servings in diets of adult soup users and non-soup users. FASEB Journal. 2003;17: A288. A Comprehensive Research Review - 2nd Edition, Revised December 2010 Himaya A, Louis-Sylvestre J. e effect of soup on satiation. Appetite. 1998;30:199-210. Jordan HA, Levitz LS, Utgoff KL, Lee HL. Role of food characteristics in behavioral change and weight loss. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1981;79:24-29. Kant AK, Graubard BI. Energy density of diets reported by American adults: association with food group intake, nutrient intake, and body weight. International Journal of Obesity (Lond). 2005;29:950–956. Khoo CS, Hartell B, Montgomery P, Gaughan C, Smith JL. Comparison of nutrient intakes of adults consuming and non consuming soup. FASEB Journal. 2003;17:A288. Kral TVE, Rolls BJ. Energy density and portion size: their independent and combined effects on energy intake. Physiology and Behavior. 2004;82:131-138. Kral TVE, Roe LS and Rolls BJ. Does nutrition information about the energy density of meals affect food intake in normal-weight women? Appetite. 2002;39:137-145. Kral TVE, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Combined effects of energy density and portion size in energy intake in women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79:962-968. Kissileff ornton J, Jordan HA. and Behavior. 1984; 32:319-332. e satiating efficiency of foods. Physiology Kris-Etherton PM, Ledikwe JM, Roe LM et al. Effects of weight loss diets on cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor prevalence. FASEB Journal. 2004;18:LB273. Ledikwe JH, Ello-Martin JA, Rolls BJ. Portion sizes and the obesity epidemic. Journal of Nutrition. 2005;135:905-909. Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Khan L, Serdula MK, Seymour JD, Tohill BC, Rolls BJ. Lowenergy-density diets are associated with high diet quality in adults in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:1172-1180. Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Seymour JD, Tohill BC, Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density is associated with energy intake and weight status in US adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;83:1362-1368. Ledikwe JH, Rolls BJ, Smiciklas-Wright H, Mitchell DC, Ard JD, Champagne C, Karanja N, Lin PH, Stevens VJ, Appel LJ. Reductions in dietary energy density are associated with weight loss in overweight and obese participants in the PREMIER trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85:1212–1221. Mattes, R. Soup and satiety. Physiology and Behavior. 2005;83:739-747. Mendoza JA, Drewnowski A, Christakis DA. Dietary energy density is associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome in U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:974–979. Muurahainen NE, Kissileff HR, Lachaussee J, Pi-Sunyer FX. Effect of a soup preload on reduction of food intake by cholecystokinin in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:R672-R680. Nolan LJ, Guss, JL, Liddle RA, Pi-Sunyer FX, Kissileff HR. Elevated plasma cholecystokinin and appetitive ratings after consumption of a liquid meal in humans. Nutrition. 2003;19:553557. 13 Norton GNM, Anderson AS, Hetherington MM. Volume and variety: relative effects on food intake. Physiology and Behavior. 2006;87:714-722. Prentice A. Manipulation of dietary fat and energy density and subsequent effects on substrate flux and food intake. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1998;67:S535-S541. Rolls BJ, Drewnowski A, Ledikwe JH. Changing the energy density of the diet as a strategy for weight management. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105:S98-S103. Rolls BJ, Bell EA. Dietary approaches to the treatment of obesity. Medical Clinics of North America. 2000;84:401-418. orwart ML. Energy density but not fat content of foods affected energy intake in lean and obese women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;69:863-871. Rolls BJ, Bell EA, Waugh BA. Increasing the volume of a food by incorporating air affects satiety in men. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;72:361-368. Rolls BJ. e role of energy density in the over consumption of fat. Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130:S268-S271. Rolls BJ. The relationship between dietary energy density and energy intake. Physiology & Behavior. 2009; 97:609-615. Rolls BJ, Kim-Harris S, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, Moran TH, Stoner SA. Satiety after preloads with different amounts of fat and carbohydrate: implications for obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1994;60:476-487. Rolls BJ, Bell EA. Intake of fat and carbohydrate: role of energy density. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;53:S166-S173. Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Reductions in portion size and energy density of foods are additive and lead to sustained decreases in energy intake. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006; 83:11-17. Rolls BJ, Fedoroff IC, Guthrie JF, Laster LJ. Foods with different satiating effects in humans. Appetite. 1990;15:115-126. Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Beach AM, Kris-Etherton PM. Provision of foods differing in energy density affects long-term weight loss. Obesity Research. 2005;13:1052-1060. orwart ML. Water incorporated into a food but not served with a food decreases energy intake in lean women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;70:448455. Savage JS, Marini M, Birch LL, Dietary energy density predicts women’s weight change over 6 y. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008, 88:677-684. Yao M, Roberts SB. Dietary energy density and weight regulation. Nutrition Reviews. 2001;59:247-258. A Comprehensive Research Review - 2nd Edition, Revised December 2010