* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download CH15 Page 1-6

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

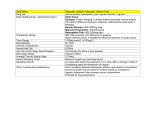

15-1 HEART FAILURE WITH REDUCED EJECTION FRACTION Cross My Heart and Hope to Live. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Level III Alison M. Walton, PharmD, BCPS 1.b. What signs, symptoms, and other information indicate the presence and type of HF in this patient? • Shortness of breath: exertional dyspnea and orthopnea (three-pillow) • Peripheral edema (3+ pitting) • Diminished peripheral pulses • JVD • HJR CASE SUMMARY A 68-year-old African-American female with past medical history significant for hypertension, CHD, MI, type 2 DM, atrial fibrillation, COPD, CKD, and heart failure (HF) presents to her primary care physician complaining of exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, and lower extremity swelling. On exam, the patient is found to have pulmonary edema and pitting edema of the lower extremities, and elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) from baseline. The patient is diagnosed with an acute exacerbation of HF and is admitted to the hospital for intravenous (IV) diuretic therapy and adjustment of her chronic medications for systolic dysfunction. The patient has been taking medications for management of her type 2 DM that may have a negative impact on her HF. Additionally, the presence of comorbid COPD and hypertension in this patient warrants consideration in light of her HF regimen. QUESTIONS Problem Identification 1.a. Create a list of this patient’s drug-related problems. Drug-related problems requiring attention at this time: • Acute exacerbation of chronic HF requiring drugs and other treatment. • Pioglitazone may worsen symptoms of HF and is contraindicated in patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III or IV HF.1 Chronic, stable drug-related problems requiring no intervention at this time: • COPD: controlled; no signs of wheezing; shortness of breath due to HF, as indicated by physical exam findings and BNP. Of note, the patient is receiving carvedilol, which is a nonselective β-blocker that may have the potential to worsen the patient’s COPD. A β1-selective agent may be a more appropriate choice for this patient. • Hypertension in the presence of HF, CHD, and diabetes with blood pressure (BP) currently at goal. • Atrial fibrillation: rate controlled; addition of digoxin may be warranted if rate becomes uncontrolled despite current therapy, or if further control of HF symptoms is necessary. • Type 2 DM: controlled; A1C indicates average blood sugar running in the 130s. • PND • Hepatosplenomegaly • LVH • Cardiomegaly • S3 gallop • Rales/pulmonary edema • Seven-kilogram weight gain • Elevated BNP: ✓BNP is a cardiac neurohormone specifically secreted from the ventricles in response to volume expansion and pressure overload. BNP levels are elevated in patients with left ventricular dysfunction and have been demonstrated to correlate with the NYHA classification, as well as prognosis. They assist clinicians in distinguishing acute congestion associated with HF from other causes of dyspnea, such as COPD, asthma, or pneumonia, particularly when the presenting symptoms are nonspecific, and physical findings are not sensitive enough to use as a basis for an accurate diagnosis. In this particular case, the elevated BNP levels suggest that the patient’s dyspnea is possibly related to volume overload and LV dysfunction. BNP measurement is a sensitive and specific test to diagnose HF in the emergency department or urgent care setting. • Displaced PMI. • Based on the information that is from the cardiac ECHO, such as the documented ejection fraction (EF) of 20% and findings suggestive of impaired ventricular relaxation, this patient should be considered to have both systolic dysfunction and diastolic dysfunction. (See also Question 1.c.) In any case, the pharmacotherapy for this patient should be selected on the basis of left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) as the underlying disease. 1.c. What is the classification and staging of chronic HF for this patient? The American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) considers EF important in the classification of HF patients. It is preferable to use the term HF with reduced EF (HFrEF) for patients with a clinical diagnosis of HF and EF ≤40%. The ACCF/AHA stages of HF emphasize the development and progression of disease, whereas the NYHA Functional Classification (FC) focuses on exercise capacity and the symptomatic status of the disease. Both the ACCF/AHA stages of HF and the NYHA FC provide meaningful and complementary information about the presence and severity of HF.2 Copyright © 2017 by McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction Julia M. Koehler, PharmD, FCCP • CKD: stable; SCr slightly increased above baseline on presentation but likely secondary to HF exacerbation leading to decreased renal perfusion. CHAPTER 15 15 • CHD: stable. 15-2 SECTION 2 ACCF/AHA Stages of HF NYHA Functional Classification A: At high risk for HF, but without structural heart disease or symptoms of HF B: Structural heart disease, but without signs or symptoms of HF C: Structural heart disease with prior or current symptoms of HF None Cardiovascular Disorders D: Refractory HF requiring specialized interventions I: No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause symptoms of HF I: No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause symptoms of HF II: Slight limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but ordinary physical activity results in symptoms of HF III: Marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but less than ordinary physical activity causes symptoms of HF IV: Unable to carry on any physical activity without symptoms of HF, or symptoms of HF at rest • Based on the above criteria, this patient would be considered to have HFrEF and classified as ACCF/AHA Stage C, NYHA FC III HF. 1.d.Could any of this patient’s problems have been caused by drug therapy? • The patient is currently taking pioglitazone, which may have contributed to volume overload. Post-marketing experience has demonstrated an increased incidence of peripheral edema in patients with or without HF, in addition to reports of pulmonary edema and pleural effusions. Peripheral edema is reported in approximately 4.8% of patients receiving pioglitazone monotherapy compared with 1.2% of patients taking placebo. When pioglitazone is combined with sulfonylureas, edema is noted in 7.5% of patients compared with 2.1% of patients on sulfonylureas alone. According to a consensus statement from the AHA and the American Diabetes Association (ADA), thiazolidinediones should not be used in patients with symptomatic or moderate-to-severe HF (ie, NYHA FC III and IV).1 Desired Outcome 2.What are the goals for the pharmacologic management of HF in this patient? • Resolve the current exacerbation of HF and achieve euvolemic status. • Reduce symptoms and improve functional capacity and quality of life. • Reduce hospitalizations and acute care visits. • Slow progression of HF and prolong survival. Therapeutic Alternatives 3.a.What diuretic therapy should be recommended for this patient initially for acute treatment of her HF exacerbation? • The patient’s home furosemide regimen is 40 mg orally given BID. For a HF exacerbation, enhancing the bioavailability of this drug is essential. Thus, furosemide must be given IV. • The equivalent IV dose to the patient’s home regimen would be 20 mg IV BID; however, a more aggressive approach would be to essentially double the dose of furosemide in addition to IV administration (ie, administer at least 40 mg IV BID). According to the 2013 ACCF/AHA HF guidelines, the management of a hospitalized patient experiencing an acute exacerbation Copyright © 2017 by McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. of HF should include IV loop diuretic therapy that equals or exceeds the chronic oral daily dose and should be given either as boluses or by continuous infusion.2 • Monitoring of diuretic therapy for this patient should include daily potassium, weights, ins and outs (I&Os), serum electrolytes, BUN, and SCr. While monitoring of serial BNPs has been done for some patients during hospitalization for acute HF exacerbation, this practice is not recommended according to the 2013 ACCF/AHA HF guidelines.2 3.b. How should this patient’s pharmacotherapy be adjusted for chronic management of her HF? • The patient’s angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) should be maintained at the current dose, as drugs within this class (as well as ACE inhibitors) have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in HFrEF. The Val-HeFT trial showed a significant reduction in the combined end point of mortality and morbidity with valsartan compared with placebo in patients with NYHA FC II, III, or IV (there was no difference in mortality alone, however).3 Based on Val-HeFT, the “target dose” for valsartan is 160 mg po BID.3 In this case, the valsartan dose is at target and is at the maximum recommended daily dose of 320 mg daily; therefore, upward titration of the valsartan dose is not necessary. • Loop diuretics, such as furosemide and torsemide, reduce morbidity in HF by reducing excess fluid overload and improving symptoms of congestion. In this case, the patient’s furosemide dose may need to be adjusted on discharge, given that the patient’s home regimen of furosemide failed to help the patient maintain a euvolemic status. ✓The patient’s adherence to her diuretic regimen and her lowsodium diet should first be considered, before an appropriate dose adjustment can be made. ✓Assuming the patient has been adherent to her diuretic regimen, an increase in furosemide dosage on discharge may be warranted. There is no need to consider adding metolazone (a thiazide-like diuretic), or switching to torsemide (a loop diuretic with more predictable oral bioavailability), at this time. • β-Blockers, such as metoprolol succinate, carvedilol, and bisoprolol, are also indicated in the management of chronic HF, as these agents, when added to either ACE inhibitors or ARBs, have also been demonstrated to further reduce morbidity and mortality.2 ✓In this case, the patient’s β-blocker dose is not at target. The dose of the β-blocker should be titrated upward to the recommended target dose (ie, that which has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in clinical trials), as tolerated. Upward dose titration of a β-blocker during an acute exacerbation of HF is not recommended. Once the patient has been diuresed and the HF exacerbation has been resolved (ie, the patient is considered “euvolemic”), the dose of the β-blocker can be increased (ie, doubled). With each dose increase, the patient should be carefully monitored for fluid retention, symptoms of worsening HF, fatigue, bradycardia, heart block, or hypotension. ✓ In addition, consideration may need to be given to switching the patient’s β-blocker to a β1-selective agent, given her concomitant COPD. A recently published retrospective analysis evaluating impact of β-blocker selectivity on outcomes in patients with HF and concomitant COPD found no evidence to suggest that noncardioselective β-blockers worsened outcomes (60-day mortality and rehospitalization) for such 15-3 ✓ In the RALES trial, treatment with spironolactone in patients with NYHA FC III or IV was associated with a 34% risk reduction in mortality and a 30% reduction in hospitalization rates.5 ✓In the EPHESUS trial, 6632 post-MI patients with LVSD (EF <35%) already receiving optimal medical therapy (ACE inhibitors or ARBs, diuretics, β-blockers, and coronary reperfusion therapy) were randomized to receive either eplerenone or placebo. Treatment with eplerenone resulted in a significant reduction in both morbidity and mortality.6 In the EMPHASIS-HF trial, patients with LVSD and mild symptoms who received eplerenone (in addition to optimal medical treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, β-blockers, and diuretics) benefited from a significant reduction in morbidity and all-cause mortality.7 ✓ Based on the findings of the EMPHASIS-HF trial, the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) issued an update to their treatment recommendations stating that aldosterone antagonists (unless contraindicated) should be added to standard therapy for HF in patients with LVSD and NYHA FC II–IV. For patients in NYHA FC II, the HFSA further recommends that the indication for an aldosterone antagonist include one additional high-risk factor, such as age >55 years, QRS duration <130 milliseconds (if LVEF 31–35%), hospitalization due to HF within the previous 6 months, or elevated BNP.8 The 2013 ACCF/AHA HF guidelines also updated their recommendations to include the use of aldosterone antagonists in HF patients (EF ≤35%) with NYHA FC II and history of prior cardiovascular hospitalization or elevated BNP levels.2 ✓Given that the patient’s serum potassium in this case is toward the low end of the normal range (and given the patient’s history of MI) and current need to increase diuretic therapy, consideration could be given to the addition of an aldosterone antagonist to further reduce morbidity and mortality. However, based on the 2013 ACCF/AHA HF guidelines, it is recommended to ensure that SCr is less than 2 mg/dL in female patients without recent worsening of SCr before starting an aldosterone antagonist (due to the risk for hyperkalemia in such patients).2 Based on these criteria, it is probably best to hold off on initiating an aldosterone antagonist for this patient at this time. If spironolactone or eplerenone were added, the patient should not be continued on a daily potassium supplement. Obviously, potassium must be monitored closely, and the recommendation is to check SCr • Digoxin: ✓ The indications for digoxin include HF and atrial fibrillation. ✓Although this patient has atrial fibrillation, the patient’s heart rate is controlled. As such, the addition of digoxin in this case for further rate control in the setting of atrial fibrillation may not be warranted yet as long as the β-blocker continues to provide adequate rate control. ✓ Although digoxin may reduce morbidity in HF by decreasing hospitalizations and improving exercise tolerance, digoxin does not reduce mortality in HF. • Hydralazine plus isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN): ✓The 2013 ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend that the combination of hydralazine plus ISDN be added to standard therapy (ie, optimal therapy with an ACE inhibitor or ARB, β-blocker, and loop diuretics) for African-American patients with NYHA FC III or IV HFrEF based on the findings of A-HeFT.2,9 As described above, although this patient’s ARB therapy is at the target dose, her β-blocker therapy has yet to be maximized. Either hydralazine/ISDN could be added now or the addition of this combination could be reconsidered as an option once the β-blocker has been changed and titrated to the recommended target dose. Consideration would need to be given to the additional pill burden associated with this regimen, as well as the potential added cost of this regimen (if the combination product is chosen rather than individual agents). Of course, hydralazine/ISDN should definitely be added in the event that the patient develops an intolerance or contraindication to ARB therapy. • Ivabradine, a selective inhibitor of the If current at the sinoatrial node, has an indication to reduce the risk of hospitalization due to worsening heart failure in adult patients with stable, symptomatic chronic HF with left ventricular EF of 35% or less, who are in sinus rhythm with a resting heart rate of at least 70 bpm, and who are receiving the maximum tolerated dose of a β-blocker or have a contraindication to β-blocker use. In the SHIFT trial, ivabradine was shown to reduce the risk of hospitalization but not mortality when compared to placebo in patients with NYHA FC II, III, or IV and a documented EF of 35% or less who were already receiving optimized therapy with β-blocker, ACE inhibitor or ARB, and aldosterone antagonist.10 Ivabradine received US approval in 2015, and this medication is first in its class. The 2016 ACC/AHA/ HFSA guidelines for the management of heart failure state that ivabradine can be beneficial to reduce HF hospitalizations for patients with stable chronic HFrEF (NYHA FC II-III) who are receiving standard HF therapy (including a beta-blocker at the maximum tolerated dose) and who are in normal sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 70 bpm or greater at rest.11 When evaluating a patient’s candidacy for ivabradine, consideration must be given to the cost of this new agent, as well as contraindications, which include abnormal heart rhythm and a resting heart rate <60 bpm prior to treatment. In this case, the patient has atrial fibrillation and is tolerating the prescribed β-blocker but not yet receiving the recommended target dose for morbidity and mortality benefit. Thus, it is best to avoid use of ivabradine and focus on upward titration of β-blocker therapy. • Sacubitril/valsartan, a combination ARB/neprilysin inhibitor, is indicated to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization due to HF in patients with HFrEF. In the PARADIGM-HF trial, sacubitril/valsartan, when compared to Copyright © 2017 by McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction • Aldosterone antagonists, including spironolactone and eplerenone, have also been demonstrated to further reduce morbidity and mortality in HFrEF (NYHA FC II–IV) when added to ACE inhibitors and diuretics, with or without digoxin. Eplerenone, specifically, demonstrated a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality when added to standard therapy for patients with known HF following acute MI. and potassium at baseline, after 3 days, after 1 week, monthly for 3 months, and then every 6 months. CHAPTER 15 patients. Spirometry was not performed to directly evaluate the impact of β-blocker use on the patients’ pulmonary function, however.4 This patient is currently receiving carvedilol, which is a nonselective α–β-blocker. A potentially appropriate recommendation would be to switch the patient’s dose to a β1-selective agent, such as metoprolol XL, which has also been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in clinical trials. It is important to also note that although a switch may be made to a more β1-selective agent, tolerability of the target dose may be a limiting factor, given the patient’s COPD and potential loss of β1 selectivity at higher doses. 15-4 SECTION 2 Cardiovascular Disorders enalapril, significantly reduced the risk for first hospitalization for worsening HF, death from cardiovascular causes, and allcause mortality.12 Sacubitril/valsartan received US approval in 2015, and sacubitril is the first neprilysin inhibitor to become available in the US. The 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guidelines state that there is “moderate quality evidence” to support the use of sacubitril/valsartan as an alternative to ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy in conjunction with beta-blockers and aldosterone antagonists in patients with chronic HFrEF. In 2015, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society, in a focused update that included recent HF studies, also acknowledged that there is “high-quality evidence” for the use of sacubitril/ valsartan over ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy alone in patients with mild-to-moderate HF with an EF of <40%, elevated BNP, or hospitalizations for HF in the past 12 months while on appropriate doses of guideline-directed medical therapy.13 When evaluating a patient’s candidacy for sacubitril/valsartan, consideration must be given to the cost of this new agent, as well as whether other morbidity- and mortality-reducing therapies for HF are currently on board and optimally dosed. In this case, the patient is currently receiving valsartan at the target (maximum recommended) dose, but titration of the patient’s β-blocker therapy toward the target dose recommended for morbidity and mortality reduction is warranted, and this would be an appropriate next step prior to considering a switch to sacubitril/valsartan. • Warfarin therapy should be continued in this patient: ✓In light of the patient’s rate-controlled atrial fibrillation and concomitant HF, anticoagulation therapy is indicated for primary stroke prevention. The 2013 ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend chronic anticoagulation therapy in patients with chronic HF with permanent/persistent/paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and an additional risk for cardioembolic stroke (ie, history of hypertension, DM, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, or ≥75 years of age).2 Chronic anticoagulation is also reasonable in patients with chronic HF who have atrial fibrillation but are without an additional risk factor for cardioembolic stroke. The selection of anticoagulation (eg, warfarin, dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban) should be individualized on the basis of several factors. 3.c. What nonpharmacologic therapy should be recommended for this patient with respect to her HF? • Although low-intensity exercise is recommended for chronic HF patients to assist with maintenance of functional capacity, bed rest during hospitalization for acute exacerbations of HF is necessary. • On discharge from the hospital, the patient should receive specific education to facilitate HF self-care. The patient should be encouraged to avoid alcohol, and a low-sodium diet (<3 g per day) should also be recommended. • The patient should be transferred to chronic oral diuretic therapy once a state of euvolemia is reached. Consideration should be given to increase the patient’s diuretic dose on discharge based on an assumption of adherence to diuretic regimen and low-sodium diet. Recommendation: Change furosemide to 60 or 80 mg by mouth twice daily. At this time, it is not necessary to consider adding metolazone or consider changing to a different diuretic (eg, torsemide). • Chronic maintenance treatment with a β-blocker should be continued in most patients requiring hospitalization in the absence of hemodynamic instability or contraindications. Based on the patient’s concomitant COPD, consideration may be given to switching the patient’s β-blocker to a β1-selective agent at an equivalent dose. Recommendation: If a switch of β-blocker is made based on desire for β1 selectivity, change carvedilol to metoprolol XL 25 mg by mouth daily. Continue to double the β-blocker dosage every 2 weeks, as tolerated, to a target dose of 200 mg once daily. (Of note, the tolerability of the selective β-blocker at the target dose may be a limiting factor in this patient due to potential loss in selectivity at higher doses in variable individuals.) If a switch of β-blocker is not made, then continue to double the carvedilol dosage every 2 weeks, as tolerated, to a target dose of 25 mg BID (since this patient weighs <85 kg). Recommendation: Continue current medications for concomitant COPD, and continue to monitor pulmonary symptoms closely with upward titration of β-blocker dose. The β-blocker dose could be increased once the acute exacerbation has resolved and the patient is euvolemic. • The patient demonstrated intolerance (cough) to an ACE inhibitor; thus, an ARB is recommended alternative therapy. The patient is receiving a target dose of an ARB; thus, no changes should be made in current therapy. Recommendation: Continue valsartan 160 mg by mouth twice daily. • The combination of hydralazine and ISDN is recommended in patients self-described as African Americans, with moderate– severe symptoms on optimal therapy. Consideration should be given to adding the combination in this patient once maintained on standard therapy, including an ARB (ACE inhibitor intolerance has been documented), a β-blocker, and a loop diuretic. Recommendation: Hydralazine and ISDN should be added once the β-blocker is titrated to the recommended target dose or maximum tolerated dose. Addition of the combination agents may be appropriate at this time; however, consideration should be given to the additional pill burden and potential cost. • An aldosterone antagonist should not be considered at this time, based on patient’s elevated SCr (SCr >2 mg/dL in a female patient). 4.What drugs, doses, schedules, and duration are best suited for the management of this patient? • The addition of digoxin is not warranted at this time. Once patient achieves optimal chronic therapy, consideration may be given to adding digoxin for further symptom control and decrease in risk for re-hospitalization. Consideration may also be given for the addition of digoxin if unable to maintain rate control for concomitant atrial fibrillation with a maximally dosed β-blocker. • An IV diuretic must be given initially for the acute HF exacerbation. The initial IV dose should equal or exceed the chronic oral dose. Recommendation: Change the patient to furosemide 40 mg IV twice daily as the preferred diuretic regimen, although furosemide 20 mg IV twice daily may be an acceptable alternative. Adjust potassium supplementation as appropriate based on laboratory results. • A switch from sacubitril/valsartan is not yet warranted at this time but could be considered if the patient remains symptomatic and/or experiences hospitalization for HF despite maximally dosed/tolerated β-blocker therapy (plus or minus hydralazine/ISDN). Optimal Plan Copyright © 2017 by McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. • The addition of ivabradine should not be considered based on the patient’s concomitant atrial fibrillation. 15-5 • Recommendation: Continue low-dose aspirin, due to the patient’s significant cardiovascular history, which includes CHD and MI. • Medications known to adversely affect the clinical status of patients with current or prior symptoms of HF should be avoided or withdrawn whenever possible. Pioglitazone is a thiazolidinedione, which carries a US black box warning stating that these agents may cause or exacerbate HF and are not recommended for use in patients with symptomatic HF. Recommendation: Pioglitazone should be discontinued in this patient with pulmonary and peripheral edema and symptomatic HF. Continue single agent glimepiride at the current dose based on controlled diabetes mellitus (A1C 6.1%). Continue to monitor control of diabetes mellitus and consider increasing dose of glimepiride if necessary. • Recommendation: Advise and encourage the patient to continue with nonpharmacologic lifestyle modifications, including low-sodium diet, alcohol avoidance, and low-intensity exercise. Outcome Evaluation 5.What clinical and laboratory parameters are needed to evaluate the therapy for achievement of the desired therapeutic outcome and to detect and prevent adverse events? Efficacy parameters: • Monitor fluid intake and urine output daily during the acute initial stages of diuresis. • Assess the patient for improvement in her exercise tolerance. • Initially, evaluate body weight daily to assess the efficacy of diuresis; the long-term goal is to return her body weight to her baseline level. Continue follow-up assessments at each visit to determine the patient’s volume status and weight. • Assess the patient at each visit for understanding and adherence with dietary sodium restrictions and medical regimen. • Assess the patient’s ability to perform routine and desired activities of daily living at each visit. The patient’s quality of life can be assessed using standard scales. Adverse effect parameters: • Signs and symptoms of hypovolemia (eg, light-headedness, hypotension, and tachycardia); vital signs should be measured frequently during the initial stages of diuresis. • Monitor serum electrolytes, especially potassium and sodium, daily initially and then periodically thereafter. Disease parameters: • The role of serum BNP levels at this time is limited to the initial diagnostic evaluation and classification of patients with possible HF. BNP (or NT-proBNP) levels should be assessed in all patients suspected of having HF especially when the diagnosis is not certain. However, the value of serial measurements of BNP to guide therapy in the acute setting is not well established. • Repeat assessment of EF may be most useful when the patient has demonstrated a major change in clinic status. Routine assessment of EF at frequent, regular, or arbitrary intervals is not recommended. Patient Education 6.What information should be provided to the patient about the medications used to treat her HF? General information: • It is important for you to take each medication daily exactly as prescribed. Even if you feel fine, do not stop taking your medications or change your dosage unless instructed to do so by your healthcare provider. • Contact your healthcare provider if you notice any new or increased shortness of breath or cough; difficulty breathing when lying flat; increased swelling in your legs, feet, or abdomen; increased fatigue or weakness with usual activities; chest pain or palpitations; or light-headedness, dizziness, or fainting. • It is advisable to weigh yourself at the same time of the day, every day. It is suggested to use the same scale every morning and weigh yourself without clothes, after using the bathroom, and before eating. Keep a record of your daily weights and contact your healthcare provider if your weight increases by 3 lb overnight or 5 lb in 1 week. • Check with your healthcare provider before starting any new medications, including nonprescription remedies. • Be sure to keep all follow-up appointments with your healthcare provider. Furosemide: • Furosemide is a diuretic that is used to maintain appropriate fluid balance in patients with HF. It is also called a “water pill,” which helps the body get rid of extra fluid so the heart does not have to work as hard. • The amount of your diuretic may change depending on how much fluid is stored in your body. Your healthcare provider will tell you the correct dose and number of times to take the medication each day. • While taking this medication, you will notice an increase in the amount of urine or in your frequency of urination. This medication is short-acting so you will have to go to the bathroom more frequently during the first few hours after taking your diuretic. Since you are taking your medication two times a day, take the first dose in the morning and the second dose no later than 4:00 pm so you will be less likely to have to get up to use the bathroom at night. Copyright © 2017 by McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction • A dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (eg, amlodipine) may be considered for additional BP lowering in HF patients. However, standard therapy for HF patients (ie, agents that have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in clinical trials) should be titrated to target doses prior to initiation of a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker for further BP control. With the initiation of an agent such as amlodipine, patients should be closely monitored due to risk of developing peripheral edema (a known side effect of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers), as well as for possible reflex tachycardia in patients with concomitant atrial fibrillation. Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (eg, verapamil and diltiazem) should be avoided in patients with HFrEF. • Renal function tests (blood urea nitrogen and SCr) should be assessed daily initially to monitor for prerenal azotemia resulting from overdiuresis. CHAPTER 15 • Continue chronic anticoagulation therapy due to concomitant atrial fibrillation. Recommendation: Continue warfarin therapy to maintain therapeutic INR (goal INR 2–3). Given that the patient’s INR is currently within this range, no dosage adjustment in warfarin is indicated at this time. 15-6 SECTION 2 • If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember, unless it is almost time for your next dose. Do not skip your diuretic when you are away from home. • This medicine sometimes causes dizziness and lightheadedness, especially when getting up from the lying or sitting position. Cardiovascular Disorders • Contact your healthcare provider if you experience dry mouth and/or increased thirst associated with decreased urine output, skin rash, tingling or loss of hearing, irregular heartbeat, fever or chills associated with sore throat, nausea and vomiting, or mood changes. • While taking a diuretic, your blood should be checked periodically to make sure that your potassium level is normal. You should only take a potassium supplement if told so by your healthcare provider. Metoprolol XL or Carvedilol: • Metoprolol XL (or carvedilol) is in a class of drugs called β-blockers. It is used to control BP as well as heart rate and reduce the workload of the heart in patients with HF. • (If change is made from carvedilol to metoprolol XL): This medication replaces your carvedilol and may be less likely to have negative effects on your COPD. • This medication should be taken by mouth once (if metoprolol XL; twice if carvedilol) daily with or without food. Your healthcare provider will slowly increase your dose until you reach the target or recommended dose for patients with HF. • If you forget to take a dose, take it as soon as you remember. If it is almost time for your next dose, skip the missed dose and return to your regular schedule. • This medicine may cause dizziness, light-headedness, or fainting. Notify your healthcare provider if you notice any of these symptoms or if you experience weight gain, difficulty breathing, or reduced urine output. • During the early phases of this drug therapy, you may actually feel worse as the dose is gradually increased. This is normal and should improve over time. • It is important to remember that this medication provides long-term improvement by reducing flare-ups of HF symptoms and prolonging survival. Valsartan: • Valsartan is in a class of drugs called ARBs. It is used to control BP and reduce the workload of the heart. This class of drugs may be prescribed for individuals unable to tolerate an ACE inhibitor, which is the case for you, as you reported a cough while taking an ACE inhibitor previously. • This medication can be taken by mouth twice daily with or without food. • If you forget to take a dose, take it as soon as you remember. If it is almost time for your next dose, skip the missed dose and return to your regular schedule. • This medicine may cause dizziness, light-headedness, or fainting, especially during hot weather. Notify your healthcare provider if you notice difficulty breathing; changes in urinary pattern; or swelling of the face, lips, or tongue. • While taking this medication, you will need to have your blood drawn occasionally to monitor potassium levels and kidney function. Copyright © 2017 by McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. Hydralazine/ISDN: • The combination of hydralazine and ISDN is used to control BP and reduce the workload of the heart in patients with HF. • The combination of medication should be taken by mouth usually three times a day. Two separate medications may be used together, or your physician may prescribe one “combination” pill. • If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember, unless it is almost time for your next dose. • The combination of medication may cause headaches, especially right after you start taking the pills. They may become less intense as you continue taking the pills, and you may take acetaminophen to help with the headaches. • Other commonly reported side effects include dizziness, nausea, vomiting, feeling light-headed, or even fainting. The combination of medication may also cause low BP. REFERENCES 1. Nesto RW, Bell D, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ADA consensus statement for thiazolidinedione use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure. Circulation 2003;108:2941–2948. 2. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:e147–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. 3. Cohn JN, Tognoni G. Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1667–1675. 4. Mentz RJ, Wojdyla D, Fiuzat M, Chiswell K, Fonarow GC, O’Connor CM. Association of beta-blocker use and selectivity with outcomes in patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (from OPTIMIZE-HF). Am J Cardiol 2013;111:582–587. 5. Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999;341:709–717. 6. Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1309–1321. 7. Zannad F, McMurray JJV, Krum H, et al., for the EMPHASIS-HF Study Group. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011;364:11–21. 8. Butler J, Ezekowitz JA, Collins JP, et al. Update on aldosterone antagonists use in heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee. J Card Fail 2012;18:265–281. 9.Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, et al. for the African-American Heart Failure Trial Investigators. Combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2049–2057. 10. Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2010;367:875–885. 11. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/ American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2016;134. doi:10.1161/CIR0000000000000435. 12. McMurray JV, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993–1004. 13. Moe GW, Ezekowitz JA, O’Meara E, et al. The 2014 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Heart Failure Management Guidelines Focus Update: Anemia, biomarkers and recent therapeutic trial implications. Can J Cardiol 2015;15:3–16.