* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

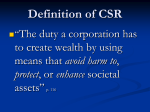

Download Corporate to management social responsibility : extending CSR to

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript