* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Semiconductors file

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

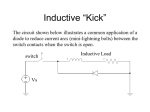

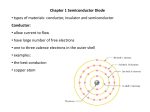

Semiconductors Covalent Bonds A crystal of pure intrinsic silicon has a regular lattice structure where the atoms are held in their position by bonds, called covalent bonds, formed by the 4 valence electrons associated with each Si atom. Electrons and Holes At sufficiently low temperatures all covalent bonds are intact and no free electrons are available. At room temperature some of the bonds are broken by thermal ionization and some electrons leave their parent atom. Thus the positive charge equal to the magnitude of the electron charge is left. A positively charged carrier or hole has been created that can move through the Si crystal structure and being available to conduct electric current like an electron. Since holes in a pure semiconductor are created by electrons that have been freed from their covalent bonds, the number of free electron are equal to the number of holes. This balance between the carrier densities is intentionally altered to produce materials in which the number of electrons or holes is greater than the other. These are known as extrinsic (or impure) semiconductors, which are said to have been doped with impurity atoms and the process is called doping. N-type semiconductor Materials in which electrons predominate are known as N-type semiconductors. N-type semiconductors are produced by doping a semiconductor with impurity atoms that have five electrons in the outermost cells. Since the impurity atom contributes five electrons, four of those electrons can participate in the covalent bonding resulting in an excess electron. Such impurity atoms are known as donor because it donates an electron to the material. Materials used for doping Si are Arsenic, Antimony and Phosphorous. P-type semiconductor Materials in which holes predominate are known as P-type semiconductors. P-type semiconductors are produced by doping a semiconductor with impurity atoms that have only three electrons in the outermost cells. Since the impurity atom contributes only three of the required four electrons necessary for covalent bonding resulting in an electron deficiency. A hole is created everywhere the impurity atom appears in the crystal. Such impurity atoms are known as acceptor because the holes they produce can readily accept electrons. Materials used for doping Si are Boron, Aluminum, Gallium and Indium. PN Junction When two blocks of N and P type materials are joined together the region where the two materials are joined is called a PN junction. Initially both regions are neutral since each acceptor/donor atom has the same number of electrons and protons. Since there is a surplus of carriers in one region compared to the other, the movement of majority carriers from one region to the other is known as diffusion current, ID. Consequently at the instant the P and N blocks are joined, electrons from the N region diffuse into the P region and holes from the P region diffuse into the N region. For each electron that leaves the N region to cross the junction into the P region it leaves behind a donor atom that now has a net positive charge. Similarly for each hole that has left the P region an acceptor atom acquires a net negative charge. The outcome of this process is that negatively charged acceptor atoms begin to line the region of the junction just inside the P block. And positively charged donor atoms accumulate just inside the N region. Accumulation of electric charge of opposite polarities in two separated regions, cause an electric field to be established between those regions. The direction of the field is from the positive N region to the negative P region, opposing the flow of electrons from the N region into the P region and the flow of holes from the P region to the N region. The region of the junction where the charged atoms are located is called a ‘depletion region’ as there are no mobile carriers. The direction of the electric field across the PN junction enables the flow of drift current from P to N region. Minority carriers drift across the PN junction, that is holes in the N region diffuse upto the depletion region and are then accelerated across the junction. Electrons in P region diffuse upto the depletion region and are accelerated across to the N region. This movement of minority carrier is known as drift current Is. For the open circuit PN junction Is = ID. D D D D e e e e D D D D e e e e D D D D D e D e D e D e A e A e A e A e A O A O A O A O A O A O A O A O A O A O A O A O O O O O Reverse Biased PN Junction Majority carriers are attracted away from the PN junction increasing the width of the depletion region and increasing the barrier potential. Thus ID decreases since majority carrier work harder to diffuse against the increased voltage. Minority carriers drift across the PN junction at the same rate as the open circuit case. Thus the drift current IS is the same. The potential difference across the depletion region is greater, but the width has also increased, leaving the electric gradient the same. Now Is >> ID. D- - + +A e e e D- - + +A e e e D- - + +A e e e D- - + +A e e e Forward Biased PN Junction The external source ensures that majority carriers are injected into the P and N regions. These injected carriers reduce the width of the depletion region and so the potential barrier. Hence ID increases. Minority carrier drift remains unchanged since the electric field across the depletion region is unchanged. D- - + +A e e e D- - + +A e e e D- - + +A e e e D- - + +A e e e Diodes What is a diode? A diode behaves as a low impedance device when we connect it in the forward bias direction. When we connect a diode in the reverse bias direction it behaves as a very high impedance device. This can be characterized in a graph: I i V However this graph only resembles an ideal diode! We will look at the different diode models later. A diode is a two-terminal P-N junction device. Diodes have two active electrodes between which the current may flow, and most are used for their unidirectional electric current property. The uni-directionality seen in most diodes is sometimes called the rectifying property. The most common function of a diode is to allow an electric current in one direction (called the forward biased condition) and to block the current in the opposite direction (the reverse biased condition). Anode Cathode + - The ideal diode i v Reverse Biased: If a negative voltage is applied to the ideal diode, no current flows and the diode behaves as an open circuit (cut off). Forward Biased: If a positive voltage is applied to the ideal diode, current flows and the diode behaves as a short circuit (turned on). The real diode Real diodes do not display such a perfect on-off directionality but have a more complex non-linear electrical characteristic, which depends on the particular type of diode technology. At very large reverse bias a process called reverse breakdown occurs which causes a large increase in current (i.e. a large number of electrons and holes are created at, and move away from the pn junction) that usually damages the device permanently. The avalanche diode is deliberately designed for use in the avalanche region. A zener diode contains a heavily doped p-n junction allowing electrons to tunnel from the valence band of the p-type material to the conduction band of the ntype material, such that the reverse voltage is “clamped” to a known value (called the zener voltage), and avalanche does not occur. Both devices, however, do have a limit to the maximum current and power in the clamped reverse voltage region. Also, following the end of forward conduction in any diode, there is reverse current for a short time. The device does not attain its full blocking capability until the reverse current ceases. The second region, at reverse biases more positive than the Vz, has only a very small reverse saturation current. In the reverse bias region for a normal P-N rectifier diode, the current through the device is very low (in the µA range). However, this is temperature dependent, and at sufficiently high temperatures, a substantial amount of reverse current can be observed (mA or more). The third region is forward but small bias, where only a small forward current is conducted. As the potential difference is increased above an arbitrarily defined “cut-in voltage” or “on-voltage” or “diode forward voltage drop (Vd)”, the diode current becomes appreciable (the level of current considered “appreciable” and the value of cut-in voltage depends on the application), and the diode presents a very low resistance. The current–voltage curve is exponential. In a normal silicon diode at rated currents, the arbitrary “cut-in” voltage is defined as 0.6 to 0.7 volts. The value is different for other diode types — Schottky diodes can be as low as 0.2 V and red light-emitting diodes (LEDs) can be 1.4 V or more and blue LEDs can be up to 4.0 V. At higher currents the forward voltage drop of the diode increases. A drop of 1 V to 1.5 V is typical at full rated current for power diodes. i Forward Compressed Scale -Vz v 0.7 V Breakdown 0.5 V Reverse Diode Models Model 1: Ideal Diode i v Model 2: Threshold Voltage Accounts for non-zero knee voltage of the device i v Model 3: Threshold & Impedance Accounts for knee voltage and non-zero impedance. i v Finding the Diode Operating Point VR R VD VB I If the diode is ideal the solution is easy because VD = 0, when D is forward biased. VB = VR + VD = IR + 0 I = VB/R For a real diode the problem is more complicated and we will need to use a load line VB = VR + VD VD = VB - VR = VB - IR I = (VB - VD)/R When I = 0, When VD = 0, VB = VD I = VB/R i VB/R IQ 0 VB VQ VD v VR To use this method we must know the device characteristics precisely. And the operating point can only be found by iterative methods. Using the threshold voltage model we can work it out as: VB = VR + VD-ideal + Vthresh = IR + Vthresh I = (VB - Vthresh) / R Using the threshold and impedance model we get: VB = VR + VD-ideal + Vthresh + VD-on = IR + Vthresh + IRON I = (VB - Vthresh) / (R+RON)