* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Role of Government in the Economy The government provides

Economic planning wikipedia , lookup

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

Participatory economics wikipedia , lookup

Production for use wikipedia , lookup

Criticisms of socialism wikipedia , lookup

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Economic democracy wikipedia , lookup

Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory wikipedia , lookup

Economics of fascism wikipedia , lookup

Post–World War II economic expansion wikipedia , lookup

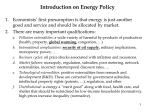

Economic calculation problem wikipedia , lookup

The Role of Government in the Economy The government provides the legal framework and services needed for the effective operation of a market economy. In the context of economic development, that mission has five primary parts: providing a legal and social framework for economic activity; providing public goods; regulating economic activity; reallocating resources; and stabilizing the economy. We will deal with each in turn. The existence of a problem in the market (or “market failure”) does not automatically mean that government intervention can allocate resources more efficiently. A substantial amount of information is required to find the optimal allocation of resources, meaning that “government failure” may end up being worse than the original market failure that government action was meant to address. Even where enough information exists to solve a problem in the market, the government may not act efficiently. Interest groups will always become involved in public policy issues that affect them directly, and their interests may not be consistent with the interests of the general public. At times there will be conflicts among the government’s many goals. If the government pursues redistributive goals—for example, by transferring income from one group of people to another through higher taxes—it may reduce the efficiency of resource allocation. Thus, there can be an explicit trade-off between efficiency and equity. Setting the Legal and Social Framework for Economic Activity By creating a sound legal framework, the government establishes the legal status of business enterprises and ensures the right and protection of private ownership, a key factor in encouraging entrepreneurship within a country’s borders. By establishing the legal rules of the game the government directs the relationships between businesses, resource suppliers, and consumers, thus improving resource allocation, which in turn supports efforts to alleviate poverty. The protection of individuals’ rights to the goods and services they exchange in a market system is almost everywhere provided by the government, although private sector protection often complements government protection. Three basic institutions protect individual rights in a market economy: police forces, national defense forces, and the courts and criminal justice system. By protecting individual rights, the government creates a system that allows individuals to interact with each other through voluntary agreement, reserving for the government the legitimate use of force. Another important function of government is the enforcement of contracts, so that citizens can make agreements with the confidence that legal recourse is available should another party fail to fulfill its commitments. The protection of rights and enforcement of contracts are necessary for a functioning economy, and they make up a sizable fraction of the public budget. Countries with well - developed laws and regulations enjoy a higher level of economic activity than those that provide few safeguards. The democratic model of checks and balances uses one branch of government to constrain the others, while democratic election of officials has the effect of circumscribing the power of the government as a whole. Providing Public Goods and Ensuring Positive Externalities Public goods and externalities (defined below) provide the main theoretical justifications for government production. Public goods are those that can be enjoyed by an unlimited number of people without prejudice to one another and without exclusion of others. Some examples include lighthouses, national defenses, the legal system, and parks. Public goods are also indivisible; they must be produced in such large units that they cannot ordinarily be sold to individual buyers. Because of these characteristics, it is not feasible to charge for their consumption; therefore private suppliers lack the incentive to supply them. Externalities, or spillovers, occur when some of the costs or benefits of an economic activity are passed on (or spill over) to parties other than the immediate seller or buyer. Some externalities have a beneficial effect on others and are referred to as positive externalities; those that have a detrimental effect are referred to as negative externalities. Pollution is an example of a negative externality, whereas investment in research and development, training, and education have positive spillovers and thus are positive externalities. The market, left on its own, will tend to produce too many goods and services that carry negative externalities (indicating a need to tax those externalities or impose restrictions on their emergence) and too few goods and services involving positive externalities (indicating a need to subsidize them or have them provided publicly). Regulating Economic Activity Regulation is called for where the private sector allocates resources inefficiently and where the imposition of rules can provide incentives for more efficient private production without the government having to become directly involved. The market does not regulate property rights, financial markets, or trade relations. It does not provide a judicial system for the enforcement of contracts. It does not enact or enforce standards to promote human health, ensure public safety, or protect the environment. The state must provide these services directly—or regulate their providers. Similarly, monopolies have no incentive to produce efficiently or to charge appropriate prices, so the state must regulate them. It does so either by regulating prices or by setting service standards under antimonopoly laws. In cases where monopolies cannot be avoided and may have particularly detrimental effects, it may be best for the public sector to provide the good or service in question. Good regulations allow markets to operate efficiently; bad ones interfere with market operations. Developing countries tend to have too little of the good kind of regulation (property rights, a well-functioning judiciary, effective environmental and financial-market regulation) and too much of the bad kind (many steps required to obtain a license to open a business, overregulation of trade, marketing boards, price controls, and so on). The stability of regulation is also important: one of the most damaging effects of ill considered state action is uncertainty. Economic actors need to be assured that the rules and regulations of an economy, the protection of property rights, and the provision of public goods are not subject to continuous change. Only in this way can a society function optimally and attract investment. Reallocating Resources There are a few closely related reasons why a government may engage in some redistribution of income. One is to improve the well-being of those members of society who are least fortunate, providing a safety net for people who have fallen on hard times (perhaps in the course of change in the economy) and ensuring that everyone has access to a minimal standard of living. Another is to provide greater equality, where that is desired as a social goal. Although these two goals have a similar ring to them, they are different and may require different public policies to bring them about. Helping the poor is not necessarily the same thing as promoting greater equality. At the extreme, the goal of equality could be achieved by confiscating the wealth of aboveaverage wealth holders and giving it to those below the average until everyone’s wealth was the same. That would destroy the incentive to be productive, however, and create a very poor society for everyone. Although a market economy benefits society as a whole, it does not benefit everyone all the time. There are always winners and losers. But whatever the origin of unequal income distribution may be, each society must decide how much state intervention it wishes to use to even it out, and to what ends. The features shared by the most egalitarian societies are a public education and health system, unemployment insurance, and public pension systems—the main components of a well-developed welfare state. Public education is redistributive in that it provides everyone with an equal opportunity. The tax system (the subject of the second part of this chapter) is another way of redistributing income, usually for the purpose of achieving greater equality (although specific policies may not have this effect). Higher taxes on upper-income individuals are often intended to further the goal of equality, but they may reduce the incentives of those affected to earn income, thereby reducing total tax revenue and limiting the options available to the state to reduce poverty. Likewise, taxation of investment income may further the goal of equality, but it also can discourage saving and investment, making the economy less productive, reducing economic growth, and leaving those at the lower end of the income scale worse off. The design of the tax structure will depend on whether the goal of redistribution is to achieve greater equality or to provide direct help for the poor and vulnerable. As individuals know how best to allocate funds to meet competing demands and so maximize their well-being, cash transfers targeted to the poor and destitute who cannot help themselves are usually the best form of redistribution. But evidence has also shown that cash payments may be misused by the poor, particularly by men who use them to buy alcohol, cigarettes, and entertainment. Also, targeted transfers may “leak” to the nonpoor; where it is impossible to control such leaks, cash transfers may not be the best policy. Community-targeted programs and geographically targeted programs are other vehicles of redistribution to the poor. In the long term, the best way of reducing poverty is usually to ensure greater access to credit, land, schooling, and health care; to provide better enforcement of property rights; and to establish programs that provide food in return for work. Work requirements are seen as a means of preventing welfare dependency, a situation thought to emerge among recipients when benefits (especially cash) are not based on quid pro quo. Recently, countries such as Brazil have been successful in introducing so-called conditional cash transfers programs that encourage parents to keep their children in school (or to take some other desired action) in return for cash compensation. The Employment Generation Scheme in Mumbai, India, employs unskilled manual laborers on public infrastructure projects; anyone who wants a job is hired. Workers are paid in basic supplies, suggesting that the poor are assumed to have limited ability to manage their own finances. Poor people can become trapped in poverty. The reasons are many: lack of education, credit, land, jobs, or roads to get to work or to bring goods to market. Perversely, dependency on social safety nets and welfare programs (even those that provide access to education and health care) can become part of the problem. Thus it is important to anticipate the consequences of redistributive policies and to act quickly to correct those that are undesirable—because they induce dependency or have some other side-effect that may outweigh the benefits achieved by the redistribution. Decades of empirical evidence from both developed and developing countries suggests that the optimal redistributive policy should comprise the following features: Welfare payments should be made in cash rather than in kind to allow recipients to exercise their judgment and discretion. A relatively high level of guaranteed income should be combined with a rapid phaseout of benefits. Benefit programs should not be financed by overtaxing those with the highest marginal incomes. Stabilizing the Economy Stabilization policies are designed to address acute fluctuations in economic activity that may be caused by demand shocks (such as an abrupt drop in demand for the country’s exports) or supply-side shocks (such as the quadrupling of oil prices in the 1970s). These fluctuations are addressed using the instruments of fiscal policy (discussed in the next section of this chapter) and monetary policy (the subject of the next chapter). Some stabilizers are automatic—that is, they are activated by movements in certain related indicators. A prime example is unemployment compensation: if the economy falls into recession, unemployment compensation payments increase as people become unemployed. Tax payments also typically decline as economic activity decreases. Such stabilizers provide channels through which the volatility of economic activity is automatically suppressed as it moves through the business cycle. Other stabilizers require a conscious policy choice. So-called active stabilization policies were very popular in the period immediately following World War II, influenced by the conventional wisdom that one of the key reasons for the Great Depression was the failure of the U.S. Federal Reserve and the American government to cut interest rates and increase spending after the crash of 1929. This view was popular at least until the 1970s, when many governments found that so called expansionary policies would not work if the problem that was impeding growth lay not in demand but rather in supply. If a government attempted to use monetary or fiscal policy to create more demand when the supply side of the economy was either at full employment or could not expand because of another bottleneck or rigidity, the result would be inflation and, in an open economy, a balance-of-payments deficit (as imports increased). The “stagflation” of the 1970s was an example of this phenomenon. Since the 1980s, skepticism has grown about the effectiveness of active, countercyclical macroeconomic policy, especially fiscal policy, which is typically harder than monetary policy to activate and fine-tune. Although monetary policy is seen to have some role in helping to stabilize economic activity, it is now widely held that the primary goal of monetary policy should be to restrain inflation. That said, in exceptional circumstances such as the recent crisis, monetary policy has an important role in helping to stabilize demand.