* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE CONCEPT OF DHAMMA AS

Silk Road transmission of Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and sexual orientation wikipedia , lookup

Early Buddhist schools wikipedia , lookup

Wat Phra Kaew wikipedia , lookup

History of Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Greco-Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and psychology wikipedia , lookup

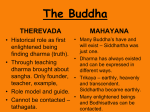

Gautama Buddha wikipedia , lookup

Buddha-nature wikipedia , lookup

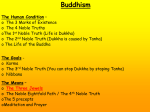

Four Noble Truths wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Western philosophy wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist ethics wikipedia , lookup

Sanghyang Adi Buddha wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism in Myanmar wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist philosophy wikipedia , lookup

Women in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Dhyāna in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Noble Eightfold Path wikipedia , lookup

Pratītyasamutpāda wikipedia , lookup

Pre-sectarian Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist cosmology of the Theravada school wikipedia , lookup