* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Guidelines for the Support and Management of People with Dementia

Parkinson's disease wikipedia , lookup

Emil Kraepelin wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric and mental health nursing wikipedia , lookup

Glossary of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Mental status examination wikipedia , lookup

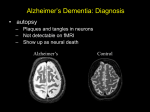

Alzheimer's disease wikipedia , lookup