* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download proscenium stage

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

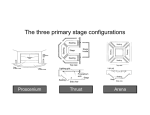

The Stages GLOSSARY Picture frame stage: A configuration in which the spectators watch the action of the play through a rectangular opening; synonym for proscenium-arch stage. Orchestra pit: The space between the stage and the auditorium, usually below stage level, that holds the orchestra. Mike: To place one or more microphones in proximity to a sound source (instrument, voice). Mix: To blend the electronic signals created by several sound sources. Balance: To adjust the loudness levels of individual signals while mixing, to achieve an appropriate blend. Sound mixer: An electronic device used to adjust the loudness and tone levels of several sources, such as microphones and tape decks. Lighting grid: A network of pipes from which lighting instruments are hung. Hanging position: A location where lighting instruments are placed. Dead hang: To suspend without means of raising or lowering. Ratchet winch: A device, used for hoisting, with a crank attached to a drum; one end of a rope or cable is attached to the drum, the other end to the load; turning the crank moves the load; a ratchet gear prevents the drum from spinning backward. Theatrical performing spaces have undergone an interesting evolution since about 1960. Influenced by a number of experimental theatre movements as well as economic pressure to make theatres usable for dance groups, symphony concerts, and esoterica such as car, home, and boat shows, companies are changing the shapes of theatres and playing spaces. Probably the most dominate trend in this evolution is the reduction of the physical and psychological barriers that separate the audience from the production. The New York production of Cats was indicative of this change. The set, a stylized representation of an incredibly cluttered junkyard, did not just sedately sit behind the proscenium arch. It negated the concept of the picture frame stage by placing elements of the set not only on the stage and apron but also in and on the orchestra pit, up the walls of the auditorium, around the balcony rail, and up into the ceiling of the auditorium. The actors made entrances through the house, touched members of the audience, and talked directly to them. This exciting new style of theatre doesn't let the audience simply sit and observe but directly involves them in the production. Innovative productions like Cats have been happening with increasing regularity throughout the country, and the theatre spaces being designed today are reflecting these production trends. Although an ingenious production concept and large budget can radically alter the appearance of almost any stage-auditorium relationship, it is still true that there are three primary stage configurations -- proscenium, thrust, and arena -- that dominate the world of theatre. PROSCENIUM STAGE The proscenium stage is also known as the picture-frame stage, because the spectators observe the action of the play through the frame of the proscenium arch. Although there is debate among theatre artists regarding the appropriateness of using this aloof stage, which forcefully separates the audience from the action, the fact remains that the proscenium stage and its machinery have, for 300 years, been the dominant mode of presentation. The reason is simple: Like the alligator and the shark, which have survived virtually unchanged through the eons, designs that work needn't be tinkered with. Proscenium Arch The proscenium arch, which gives this type of stage its name, is a direct descendant of the proskenium and skene of the Greek theatres. This arch, which separates the stage from the auditorium, can vary greatly in both height and width. The average theatre (with 300 to 500 seats), generally has a proscenium arch that is eighteen to twenty-two feet high and thirty-six to forty feet wide. Stage The playing area behind, or upstage, of the proscenium arch is referred to as the stage. A stage floor is a working surface that serves a number of diverse functions. For the actors, it must provide a firm, resilient, nonskid (but not too sticky) surface that facilitates movement. For scenic purposes, a stage floor needs to be paintable. It should also be reasonably resistant to splintering and gouging caused by heavy stage wagons and other scenic pieces, and it should slightly muffle the sound of footfalls and shifting scenery. Although many directors choose to move the action of their productions forward onto the apron to bring the play closer to the audience, the primary playing area for most proscenium productions still remains the stage. Wings The spaces on either side of the stage are called the wings. Wings are primarily used for storage. During a multiscene production, all sorts of scenic elements, props, and other equipment are stored in the wings until they are needed on stage. Apron The apron, or forestage, is an extension of the stage from the proscenium arch toward the audience. It stretches across the proscenium arch to the walls of the auditorium and can vary in depth from a narrow sliver only three or four feet deep to as much as ten or fifteen feet. It generally extends for five to fifteen feet beyond either end of the proscenium arch. Orchestra Pit Many proscenium theatres have an orchestra pit, which is almost always placed between the apron and the audience. It is used to hold the pit band, or orchestra, during performances that need live music. To hold an orchestra, the pit obviously needs to be fairly large. Most pits extend the full width of the proscenium and are roughly eight to twelve feet across. The depth of the pit varies, but a good pit is deep enough so that the orchestra won't interfere with the spectators' view of the stage. Obviously, the size of the orchestra pit imposes a formidable gulf between the audience and stage when it is not in use. Various solutions have been adopted to remedy this situation. In some theatres, the orchestra pit is hidden beneath removable floor panels under the apron; when the pit is needed for a production, the floor panels are removed. In other theatres, the pit is placed beneath the auditorium floor. When not in use it is covered with removable panels, and auditorium seats are placed on top. This method has the obvious advantage that additional tickets can be sold when the pit isn't being used. In some theatres, the entire forestage area (apron, orchestra pit, front of the auditorium) is composed of one or more hydraulic lifts. With their great lifting power, it is possible to raise or lower whole sections of the stage. When more than one lift is used, they are able to shape the forestage into a variety of configurations . Bally's Hotel in Las Vegas has created what may be the ultimate answer to the orchestra pit: There isn't any. The orchestra plays in a room in the basement of the hotel while watching the production on closed-circuit television. Each section of the orchestra is miked, and the sound is mixed and balanced with that of the singers before it is amplified and sent into the auditorium. Although this solution works well in the high-tech atmosphere of Las Vegas, it is doubtful that every musical director would feel comfortable working in this remote and seemingly disconnected manner. Auditorium The shape of the typical proscenium theatre auditorium, or house, is roughly rectangular, with the proscenium arch located on one of the narrow ends of the rectangle. Normally, each seat is approximately perpendicular to the proscenium arch. To reduce the reflection of sound waves in an auditorium, none of its finished surfaces (walls, ceiling, floor) should be parallel with any others. Thus, the side walls of most auditoriums angle out from the proscenium arch in the shape of a slightly opened fan. The rear wall of the auditorium is almost always curved, and the ceiling generally slopes down toward the rear of the house. The floor of the auditorium is raked, or inclined, from the stage to the rear of the house. Angling of the house floor improves not only the acoustics of the theatre but also the spectators' view of the stage, by elevating each successive row. The lighting control booth is generally located at the back of the auditorium. It normally has one or more large windows to provide the light-board operator(s) with an unobstructed view of the stage. Although a sound booth with a large window (which can be opened) is usually located in a similar back-of-house location, the sound operator frequently runs the sound mixer from a position in the auditorium so that he or she can hear what the audience is hearing and balance all the sound sources accordingly. The resulting sound "picture" has a focal point, usually the voice of the actor or singer. THRUST STAGE The thrust stage isn't a new development. Medieval audiences gathered on three sides of the pageant wagons and platform stages to watch passion plays, and research indicates that the Globe Theatre also had a thrust stage. The thrust stage was rediscovered by directors who wanted to move the action of the play out of what they felt were the artificial and limiting confines of the proscenium stage. Whatever the reasons, the midtwentieth century saw the birth of a large number of thrust stage theatres in the United States. The stage of the thrust theatre projects into, and is surrounded on three sides by, the audience, so tall flats, drops, and vertical masking cannot be used where they would interfere with the spectators' view of the stage. But on the fourth, or upstage, side of the stage, drops and flats can be placed to help visually describe the play's location. Although entrances are frequently made through openings in the upstage wall, the house is also used for this purpose. The lighting grid in a thrust theatre is usually suspended over the entire stage and auditorium space, so instruments can be hung wherever necessary to effectively light the playing area. Lighting grids vary in complexity from designs that hide the lighting instruments from the spectators' view to simple pipe grids from which the lights are hung in full view. Access to the simpler pipe grids is usually from a rolling ladder placed on the stage. The more complex grids frequently have walkways above the pipes to allow electricians to adjust the lighting instruments from above. In addition to the grid, there are usually some additional hanging positions above the house, either open pipes or some type of semiconcealed location. Some thrust theatres retain a vestigial proscenium arch on the upstage wall as well as a small backstage area. Although battens are frequently dead hung above this backstage space, some theatres have installed ratchet winches, rope sets, or counterweight sets so the battens can be raised and lowered. The lighting and sound booths are generally located at the back of the house directly facing the stage, although nothing stronger than tradition prevents them from being placed at any location in the auditorium that provides an unobstructed view of the stage. Again, as in the proscenium theatre, and for the same reasons, the sound operator frequently chooses to run the mixing board from a position in the house rather than from the sound booth. ARENA SATGE The arena stage is another step in the development of an intimate actor-audience theatre. The audience surrounds the stage and is much closer to the action of the play than in either the proscenium or thrust theatres. The scenery used on an arena stage is extremely minimal. Because the audience surrounds the stage, designing for the arena theatre provides a challenge to all the designers. Anything used on an arena stage -- sets, costumes, makeup, props -- must be carefully selected to clearly specify the period, mood, and feeling of the play. Additionally, everything must be well constructed, because the audience sits almost on top of the stage and can see every construction detail. As in the thrust stage theatre, the space above the arena stage has a lighting grid rather than a fly loft. The lighting grid frequently covers not only the stage but the auditorium as well. The stage manager and the lighting and sound operators need to have a clear view of the stage. Many arena theatres have an elevated deck running around the perimeter of the auditorium to provide these people with a variety of potential work locations. Some arena theatres have a traditional lighting booth and sound-control booth rather than flexible work stations. BLACK BOX THEATRES The flexible staging of black box theatres encourages, and demands, ingenuity from the production-design team. These new design-it-yourself performance spaces are a direct result of a number of experimental theatre movements that sought to break down the visual and psychological barriers created by the proscenium stage. In black box theatres (so named because they are usually painted black and have a simple rectangular shape), the seating is generally on movable bleacherlike modules that can be arranged in any number of ways around the playing space. Although the space can be set up in traditional proscenium, thrust, or arena configurations, it can also be aligned into excitingly different staging arrangements that support the production concept for particular productions. This type of theatre is fun to work in, and every production creates a challenge to the ingenuity of the production design team. The black box theatre was developed partially as a reaction against the artistic confines of more formal types of stage space. Consequently, there isn't a great deal of specific stage equipment associated with it. However, there is a lighting grid, similar to that of the arena theatre, located above the stage and auditorium space, and there is usually a variety of additional hanging locations. "FOUND" THEATRE SPACES Found theatre spaces lend a great deal of credence to the statement that all theatre needs is "two boards and a passion." These theatres are housed in structures that were originally designed for some other purpose. Almost every conceivable type. of space has been, or could be, converted for use as a theatre. In Tucson, Arizona, alone, a supermarket, movie house, lumberyard, feed store, office building, and restaurant have been converted to theatrical use, all within the past fifteen years. The Lafayette Square Theatre in New York City houses five theatres in what used to be a library. The only criteria for conversion seem to be sufficient square footage in the building to house a stage and its audience and sufficient nearby parking or public transportation. Found theatre spaces are frequently converted into black box theatres, but a number of converting companies have opted for the more traditional arena or thrust stage configurations. For some producing groups, the appeal of the conversed space lies in the intimacy of the audience-actor relationship that is inherent in these generally small theatres. For others, the lower production costs of the smaller, more intimate theatre forms are an asset. STAGE DIRECTIONS It can be frustrating trying to tell an actor what direction to move or telling a technician that "I want the sofa a little further to the left." "My left?" he asks. "No, that way. Over there." Through the years, a system of stage directions has evolved to help clear up these problems. On the American proscenium and thrust stages, stage directions are understood to mean that you are standing on the stage and looking into the auditorium. Stage left is to your left and stage right is to your right. Upstage is behind you, and downstage is in front of you. The terms upstage and downstage probably evolved in the sixteenth or seventeenth century during the era of raked stages, when you literally went up the slope of the stage in moving upstage. Stage directions in Europe are noted in a slightly different manner. Upstage and downstage are the same, but right and left are reversed from the American system, being given in reference to the auditorium rather than the stage. Stage directions for arena stages cannot use this system, since the audience surrounds the stage. When this happens, it is much easier to describe the stage directions by referring to one direction as north, and then the remaining directions are understood to be south, east, and west.