* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chapter 27 PowerPoint

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

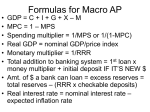

27 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships McGraw-Hill/Irwin Copyright © 2012 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. The Great Depression • The 1930s changed the view of economist around the world who once believed that markets would automatically adjust to their long-run potentials and that longterm recessionary conditions were impossible. • The Great Depression changed that: – 1929-1933: real GDP decreases by 30% – 1933: Unemployment is 25%; by 1939 at 17% John Maynard Keynes • Economist; developed a theory that explained long term unemployment and a recipe to stimulate recovery. • Keynes believed that spending motivated firms to supply goods and services. – If consumers and firms were pessimistic about the future, firms would cut back production. – Essentially – less spending would lead to less output. Keynes cont’d. • Rejected the belief that lower wages and interest rates would get the economy back on track… argued that wages and interest rates are highly inflexible. • Instead, he believed that powerful trade unions and large corporations would be able to maintain their wages and prices at a high level and that’s what would reinvigorate the economy. • Also believe that lower interest rates would fail to stimulate additional investment. Output, Employment and Keynes • According to Keynes: – Equilibrium takes place when total spending in the economy is equal to current output. • When this happens, firms can sell what they are currently producing, inventories won’t rise or fall and they won’t have to adjust their output. – Believed that changes in output, not prices, would stimulate economy towards equilibrium. • Increase in consumption would leading to a reduction in inventory and businesses would have to respond by increasing their output which means more jobs (and vice versa) Output and Employment • Keynes believed that 1930s consumers were unwilling to spend much because reduction in stock prices and the value of assets had reduced their wealth and income. People were super pessimistic about their future. • Businesses responded by cutting output and stopped investing which led to underutilization and high unemployment. Keynes and the Multiplier Principle • Keynes believed that market forces could not be counted on to maintain spending levels consistent with full employment because even minor disturbances will often be amplified into major disruptions. • The multiplier principle explains this: – Builds on the point that one individual’s expenditures becomes the income of another. – People will spend part of their income on consumption which will generate income for others – eventually total income will expand by a multiple of the initial increase in spending. Income Consumption and Saving • Consumption and saving • Primarily determined by Disposable Income • Direct relationship (if DI increases, consumption increases but so does saving) – Consumption schedule • Planned household spending – shows relationship between DI and C – Saving schedule • DI minus C = savings • Dissaving can occur (consuming in excess of after-tax income) LO1 27-8 Income, Consumption, and Saving • The 45 deg. line shows where C = DI ; no economic value just serves as a reference • The green line Shows actual C • In between the two Lines is where Savings occurs. LO1 27-9 Consumption and Saving Schedules Consumption and Saving Schedules (in Billions) and Propensities to Consume and Save (4) (1) Level of Output and Income GDP=DI (2) Consumption (C) (3) Saving (S), (1) – (2) (1) $370 $375 (6) Average Propensity to Consume (APC), Average Propensity to Save (APS), (2)/(1) $-5 (7) Marginal Propensity to Consume Marginal Propensity to Save (3)/(1) (MPC), (2)/(1)* (MPS), (3)/(1)* 1.01 -.01 .75 .25 (5) (2) 390 390 0 1.00 .00 .75 .25 (3) 410 405 5 .99 .01 .75 .25 (4) 430 420 10 .98 .02 .75 .25 (5) 450 435 15 .97 .03 .75 .25 (6) 470 450 20 .96 .04 .75 .25 (7) 490 465 25 .95 .05 .75 .25 (8) 510 480 30 .94 .06 .75 .25 (9) 530 495 35 .93 .07 .75 .25 (10) 550 510 40 .93 .07 .75 .25 LO1 27-10 Consumption (billions of dollars) Consumption and Saving Schedules 500 C 475 450 425 Saving $5 billion Consumption schedule 400 375 Dissaving $5 billion $390 is “break-even” where C=DI Saving (billions of dollars) 45° 370 390 410 430 450 470 490 510 530 550 50 25 0 Dissaving Saving schedule S $5 billion Saving $5 billion 370 390 410 430 450 470 490 510 530 550 Disposable income (billions of dollars) LO1 27-11 Average Propensities • It is fact that household will either consume or save a proportion of their total income. We can measure how much they C or S by creating proportions (fractions) – Average propensity to consume (APC) •Fraction of total income consumed – Average propensity to save (APS) •Fraction of total income saved consumption APC = income APC + APS = 1 LO1 APS = saving income Because DI is either C or S, the fraction consumed must exhaust that income. 27-12 Example APC/APS APC = 450/470 = 45/47 = .96 or 96% APS = 20/470 = 2/47 = .4 or 4% .96 + .4 = 1 Global Perspective Here, we can see that in 2009 – Australia, the US and Canada all had much higher APCs compared to other economically developed nations. This means that on average, people were consuming more than they were saving in these countries. LO1 27-14 Food for thought… • Just because households consume a certain proportion of a particular total income does not guarantee that they will always consumer their same proportion of any change in income they might receive. • Keynes referred to this proportion of any change in income consumed is called the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). (Remember, marginal means extra or a change in…) Marginal Propensities • Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) • Proportion of a change in income consumed • Marginal propensity to save (MPS) • Proportion of a change in income saved MPC = change in consumption change in income MPS = change in saving change in income MPC + MPS = 1 Because a change in DI can be C or S, the sum of MPC and MPS for any change in DI will be 1. LO1 27-16 Example MPC/MPS Let’s say that income levels rise by $20 billion. MPC = 15/20 = ¾ or 75% MPS = 5/20 = ¼ or 25% .75 + .25 = 1 Marginal Propensities C 15 MPC = 20 = .75 Consumption The MPC is the slope of the consumption schedule C ____ DI C ($15) The MPS is the slope of the savings schedule S _____ DI LO1 Saving DI ($20) MPS = 5 = .25 20 S S ($5) DI ($20) Disposable income 27-18 Non-Income Determinants • Amount of disposable income is the main determinant of how much people will save or consume. • Other determinants (cause entire schedule to shift) • Wealth (total assets – total liabilities) • Expectations (anticipation of future prices will affect saving and spending today) • Borrowing (Borrowing means that household can consume more today beyond what would be possible if its spending limits where within its DI) • Real interest rates (when real i fall; households borrow more, consume more and save less. Lower i on mortgage lowers payments and encourage consumers to buy cars for example. Higher i has the opposite effect.) • LO2 These determinants cause consumption to go in one direction and savings to go in another. 27-19 Because C+S=DI…. C1 Consumption C0 Increases in Consumption Means… o 45 o Saving Disposable Income S0 S1 o Disposable Income A Decrease In Saving Because C+S=DI…. Consumption C0 C2 Decreases in Consumption Means… o 45 o Disposable Income Saving S2 S0 o Disposable Income An Increase In Saving EXPENDITURE PLANS AND REAL GDP Figure 29.3 shows shifts in the consumption function. 1. Consumption expenditure increases and the consumption function shifts upward if • The real interest rate falls • Wealth increases • Expected future income increases EXPENDITURE PLANS AND REAL GDP 2. Consumption expenditure decreases and the consumption function shifts downward if •The real interest rate rises •Wealth decreases •Expected future income decreases Other Important Considerations • Switching to real GDP – Economists will shift their focus from the relationship between C and S, to how C(and S) impact real domestic output) • Changes along schedules – Movement along the consumption sched. Indicates a change in the amount consumed; a total shift of the sched. Is caused by any nonincome determinants (WEBR) • Simultaneous shifts – If consumption and savings shift in the opposite direction, this will mean big changes for real GDP • Taxation – will cause schedules to shift in the same direction. • Stability – C & S schedules are generally stable unless there are major tax increases LO2 or decreases. This is because C-S decisions are based on the long-term (saving for emergencies or retirement). 27-24 Shifts of C & S Schedules C1 C0 Consumption (billions of dollars) C2 Saving (billions of dollars) 45° LO2 0 S2 S0 S1 + 0 Real GDP (billions of dollars) 27-25 Interest-Rate-Investment • Remember that firms invest in capital when their marginal benefit outweighs their marginal costs. – The “marginal benefit” is referred to as the “expected rate of return” – – (what they hope to get out of the investment…profit) The real interest rate is a factor for firms to consider as a “marginal cost” of investing. Expected returns (profits) and interest rates are determinants of investments. • Let’s say we want to invest in a new fryer for our restaurant that costs $1,000 and has a useful life of 1 year. This new fryer will increase output and sales revenue – the net expected revenue is $1,100. After we subtract the cost of the investment from the net revenue (1100-100 = $100) we can figure out the rate of return by profit/cost of investment. (100/1000 = .10 or 10%. The rate of return is 10% profit) LO3 27-26 Interest-Rate-Investment We can also calculate how interest rates will affect our decision to invest in capital. • Let’s say the i on the fryer machine was 7%. To calculate how much we will pay in i you multiply the cost of the investment by the i (1000 x .07 = $70) • When compared to our rate of return ($100), this i is favorable. After paying our liabilities, we will profit $30. • Generally, if the rate of return exceeds the i the investment should be undertaken. But if the i exceeds the rate of return, the investment should not be undertaken. Only real i, not nominal is critical to consider for I. • But what about inflation? If the nominal i was 15 and real is 10 (15-10 = 5% adjusted for inflation). Still profitable… LO3 27-27 Investment Demand Curve 16% Investment (billions of dollars) $0 14 5 12 10 10 15 8 20 6 25 4 30 2 35 0 40 Expected rate of return, r and real interest rate, i (percents) (r) and (i) Shows the amount of investment forthcoming at each real i. The levels of investment depend on the rate of return (r) and the real i. 16 14 Investment demand curve 12 10 8 6 4 2 ID 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 Investment (billions of dollars) What is the relationship between r and i? If i were to fall from 6% to 4% what will happen to investment? LO3 27-28 Shifts of Investment Demand • Movement along the investment demand curve indicates a • change in r and i and how that impacts investment. There are other determinants that will shift the entire curve: – Taxes: increases in taxes lower business profitability and investments; shifts curve to the left/ and – Technological Changes: stimulate investment and shift curve to the right – Acquisition, maintenance, and operating costs: the costs of capital goods and the cost to maintain them can affect the r; when costs rise, investment demand will fall (left) and vice versa. – Planned inventory changes: if firms are planning to increase inventory, investment demand will increase and vice versa. – Expectations: If executive become more optimistic about future sales, costs and profits, investment demand will increases and vice versa. – Stock of capital goods on hand: When the economy is overstocked with production facilities, the need for new production decreases and investment demand falls and vice versa. LO4 27-29 Expected rate of return, r, and real interest rate, i (percents) Shifts of Investment Demand Increase in investment demand Decrease in investment demand 0 LO4 ID2 ID0 ID1 Investment (billions of dollars) 27-30 Instability of Investment • We have to keep in mind that investments can be relatively unstable – it’s a volatile component of total spending because you can guarantee rates of return. – Variability of expectations: changes in exchange rates, trade barriers, – – – LO4 laws, stock market prices, wars, etc. all impact businesses and can impact their expectations. Durability: capital goods have an indefinite life span. Can’t be guaranteed any sort of return. Irregularity of innovation: waves of investment in time recede because the “new” wears off… Variability of profits: can’t guarantee profits from year to year. 27-31 Instability of Investment Changes in investment spending is often greater than changes in GDP in any given year. Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, http://www.bea.gov. LO4 27-32 Keynes and the Multiplier Principle • Keynes believed that market forces could not be counted on to maintain spending levels consistent with full employment because even minor disturbances will often be amplified into major disruptions. • The multiplier principle explains this: – Builds on the point that one individual’s expenditures becomes the income of another. – People will spend part of their income on consumption which will generate income for others – eventually total income will expand by a multiple of the initial increase in spending. The Multiplier Effect • A change in spending changes real GDP more than the initial change in spending itself. – More spending = higher GDP; Less spending = lower – GDP But investment can lead to more output and income, which would lead to more spending and that would be larger than just the investment itself. • The multiplier determines how much larger that change will be. It is the ratio of change in GDP to the change in spending. Multiplier = change in real GDP initial change in spending Change in GDP = multiplier x initial change in spending LO5 27-34 The Multiplier Effect Multiplier = change in real GDP initial change in spending • Let’s say that an investment economy rises by $30 billion and GDP increases by $90 billion, then the multiplier is… • 90/30 = 3 (multiplier) LO5 27-35 The Multiplier Effect Multiplier = change in real GDP initial change in spending • The multiplier effect shows us that there is a chain of spending that occurs, that however small at each step, will cumulate to a multiple change in GDP. • Essentially, initial changes in spending will produce magnified changes in output and income over time. LO5 27-36 The Multiplier Effect (1) Change in Income (in bill.) (2) Change in Consumption (MPC = .75) (3) Change in Saving (MPS = .25) $5.00 $3.75 $1.25 Second round 3.75 2.81 .94 Third round 2.81 2.11 .70 Fourth round 2.11 1.58 .53 Fifth round 1.58 1.19 .39 All other rounds 4.75 3.56 1.19 $20.00 $15.00 $5.00 Increase in investment of $5.00 Total Cumulative income, GDP (billions of dollars) 20.00 $4.75 15.25 13.67 $1.58 $2.11 11.56 $2.81 8.75 $3.75 5.00 $5.00 1 LO5 2 3 4 5 All others 27-37 Multiplier and Marginal Propensities • Multiplier and MPC are directly related • Large MPC results in larger increases in spending • Multiplier and MPS inversely related • Large MPS results in smaller increases in spending Multiplier = 1 1- MPC Because MPC + MPS = 1, we can also write the multiplier formula as: LO5 Multiplier = 1 MPS 27-38 Multiplier and Marginal Propensities MPC Multiplier .9 10 .8 5 .75 4 .67 .5 LO5 3 2 27-39 The Actual Multiplier Effect? • Actual multiplier is lower than the examples provided: – Consumers buy imported products (impacts GDP) – Households pay income taxes (affects spending – – LO5 ability) Inflation (sometimes inflation is assumed to be the culprit rather than actual changes in real GDP; increased consumption can actually drive prices up – not always inflation) Multiplier may be 0 (Economists actually disagree about the multiplier effect – range from 2.5 to 0. ) 27-40