* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Lecture 25 Local Coastal Zone Management and GIS

Operations management wikipedia , lookup

High-commitment management wikipedia , lookup

Operations research wikipedia , lookup

Management consulting wikipedia , lookup

Investment management wikipedia , lookup

International Council of Management Consulting Institutes wikipedia , lookup

Ecosystem-based management wikipedia , lookup

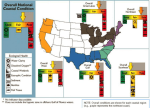

Lecture 25 Local Coastal Zone Management and GIS Learning Objectives 25.1 Why is coastal zone management at the local jurisdiction level an important concern for many areas around the world? How should we interpret “local”? 25.2 How do conventional management techniques relate to growth management techniques for communities? Why are growth management techniques commonly associated with coastal areas? 25.3 How is GIS useful in promoting communication, cooperation, coordination and collaboration among local governments? Local Coastal Management Coastal counties comprise only 17 percent of the U.S. contiguous land area. However, as of 2003 53% of the population lives in these areas. Many other people visit these areas on vacation and business, and thus see them as having significant value worthy of protection (Crosset, K., Culliton, T., Wiley, P., and Goodspeed, R. (September 2004) Population Trends Along the Coastal United States: 1980-2008. Coastal Trends Report Series. Silver Spring, MD: NOAA.) Town(ship)s, Cities, and Counties can be considered “local” when it comes to coastal zone management. Management is about planning, budgeting improvement programs and implementing (intended) improvements in those jurisdictions through projects. Many day-to-day management decisions are made at the local level. There are 19,000+ municipalities and 3,100+ counties in US. Many decisions that influence coastal resources are made a local level. Furthermore, remember decisions often have diverse stakeholder groups who have interest in, and often participate in, such decisions. Regulation of land use development decisions is the primary responsibility of local jurisdictions, but public, private and not-for-profit entities make decisions. Beatley, Brower and Schwab argue that land use and comprehensive planning can be most responsive to the interests, needs, issues, and concerns of the constituencies at the local level. Furthermore, they suggest that coastal communities can become sustainable coastal communities. Sustainable coastal communities (as counties, cities, towns, and villages) seek to minimize their destructive impact on natural systems and the natural environment, create highly livable and enduring places build communities that are socially just and in which the needs of all groups in the community are addressed That “sustainability” perspective follows from the 1987 report of the Brundtland Commission (and many subsequent initiatives) that popularized the concept of sustainable development, defining it as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development 1987, p.8) Characteristics of a sustainable coastal community (Beatley, Brower, Schwab 2002, p. 198) Minimize disruption of natural systems and avoid consumption and destruction of ecologically sensitive lands (e.g., coastal wetlands, maritime forests, species habitat, and areas rich in biodiversity), Minimize their ecological footprints and reduce the wasteful consumption of land; promote compact, contiguous development patterns and encourage separation of urban and urbanizable lands from natural and rural lands, Avoid environmental hazards and reduce exposure of people and property to coastal hazards by keeping people and property out of coastal floodplains, high-erosion zones, and inlet hazards areas, Reduce waste generation (e.g., air pollution, water pollution) and the consumption of nonrenewable resources and promote the recycling and reuse of waste products, respecting earth’s ecological capital to supply ecological services; understand and live within the natural ecological carrying capacity of the area, Reduce dependency on the automobile and promote a more balanced and integrated transportation system; encourage and facilitate the use of a variety of alternative and more sustainable modes of transportation (e.g., mass transit, bicycles, walking) and integrate land use and transportation decision making, Promote and develop a sense of place and understanding and appreciation of the bioregional context in which they are situated, Foster a high degree of livability; aesthetically pleasing and visually stimulating community whose design uplifts human spirit, Incorporate a strong public and civic dimension, that is reflected in the communities spatial and physical form; promoting places of public interaction that help shape a sense of identity, Achieve a human scale and encourage integration of uses and activities (e.g., commercial and residential) and enhance livability in various ways (e.g., reduce crime, reduce auto dependent, develop vibrant spaces), Seek to eradicate poverty and ensure a dignified life for all residents; provide affordable housing, health care, meaningful employment, and reduce separation between income groups, Value participation of all citizens (residents) and provide opportunities for participation in governance. The relationship between those key concepts of sustainable communities and several key functions of governance in which local governments are involved is central to implementing coastal zone management. We will elaborate on sustainability management in the next lecture, but first let us consider conventional management and then growth management techniques. Conventional Management Techniques – a step toward growth management - Functional plans – single theme (land use, transportation, water resource) in isolation - Zoning ordinances – cluster - Setback requirements - Subdivision ordinances - Transfer of development rights from environmentally sensitive sites to urban suburban sites Conventional (community) management is practiced in almost all 19,000+ municipalities and 3,100+ counties to address community change. However, some communities are growing (in population size with associated impacts) more rapidly; thus, some have a recognized need for more growth guidance in so-called “growth management” and “new urbanism”. Growth Management – a step toward sustainability Many local jurisdictions are managing development with a growth management framework. The overall policy framework is commonly developed at the state level and then passed to the counties and cities for implementation. That implementation is often coordinated at a regional level – thus drawing together state, regional and local efforts in managing growth. As of 2006, 11 of 50 US states enacted growth management laws - 3 states - Florida, New Jersey, and Oregon - have been using top-down controls, i.e., a strong state level control to encourage development growth (consider coastal orientation of these states; which is not surprising remembering the 17% of US counties has 50% of population) - 8 states - Georgia, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington – use bottom-up control, i.e., stronger local level control. - A 12th state – California – is beginning to use a combination of both. - 27 states have some role in growth management, but it is not substantial as in the previous eleven. - 13 have no mandates in the form of state laws or regulations, as growth (if any) is not viewed as problematic. In “top down planning” states, such as Oregon, goals are more specific at the state level than they are in “bottom up planning” states like Washington. In top-down states, the goals are stated in such a way that all counties within the state plan in the same way. In bottom-up planning states, the goals are generalized, but made specific by local jurisdiction implementation as long as the jurisdiction makes some kind of plan. Certain thresholds about development can be different from jurisdiction to jurisdiction (i.e., county to county and city to city). Newer techniques for growth management - in addition to conventional techniques, there are additional techniques needed for managing rapid growth - Comprehensive plans as opposed to more conventional functional plans - Zoning ordinances for special character and sense of place, e.g., high density cluster development with open space adjacent - Concurrency management – capital facility infrastructure and land use in connection with each other - Urban growth boundaries – foster densification in already urban areas; protect rural areas When we consider coastal zone management, the issues of concern do not often align with the approaches that are in place to solve most conventional problems. That is, conventional and growth management techniques do not necessarily focus on addressing coastal problems, e.g., degradation of Puget sound nearshore habitat or degradation of salmon habitat. Efforts to address those concerns need to be more “cross-cutting”, that is they cut across jurisdictions. GIS is useful for fostering a participatory approach (i.e., communication, cooperation, coordination and collaboration) to salmon habitat recovery due to the inherent character of information integration that underlies the technology. Modes of participation: - communication: agree to talk with one another - cooperation: agree to exchange information products to use as each sees fit - coordination: agree to sequence the development of separately created information products for the benefit of both - collaboration: agree to work together and jointly develop products for the benefit of both Local partners working together to protect and restore salmon habitat. Let us consider an example of a participatory approach directed at salmon recovery involving watershed management based on water resource inventory areas. Plan and project activity occurs among a coalition of local governments, business, and not-for-profit groups, principally funded by local governments due to mandates. Efforts in King County are occurring in WRIAs 7-10. For example in WIRA 9, 16 local governments are developing a salmon habitat recovery plan. Carrying out the plan recommendations will protect and restore a healthy watershed ecosystem for both people and fish. Staff from King County Dept of Natural Resources are provided under contract to assist with coordination, with funds coming from those 16 local governments. Chinook salmon are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. In WRIA 9 citizens, scientists, businesses, environmentalists, and governments are worked together to completed a science-based Salmon Habitat Plan. See the “local action map” on right side of page for projects that implementation the plan. Prioritization of Marine Shorelines of WRIA 9 for Juvenile Salmonid Habitat Protection and Restoration May 2006 Green/Duwamish and Central Puget Sound Watershed Water Resource Inventory Area (WRIA) 9 http://dnr.metrokc.gov/Wrias/9/NearshoreHabitatPrioritization.htm The Salmon Habitat Recovery effort is different but related to the Puget Sound Nearshore Partnership because of the difference in “place”. Consider the nearshore subwatersheds on the action plan map. The significant coordination of efforts we are seeing is only a “tip of the iceberg” for what is needed to plan, program, and implement sustainable coastal communities. What is needed is full recognition of the links among functional themes (land use, transportation, water resources) as well as links among decision processes (planning, improvement programming, projects). Those links are considered more thoroughly in the next session as a way to practically characterize Beatley, Brower and Schwab’s “Framework for Sustainable Coastal Development”.