* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download consumer demand

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

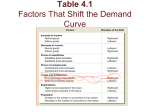

CHAPTER 4 CONSUMER DEMAND WHAT IS THIS CHAPTER ALL ABOUT? The chapter introduces students to the analysis of consumption patterns and the basic explanations of consumer behavior. The emphasis here is on the microeconomic aspects of consumption and how consumption decisions are influenced by tastes, prices, income, expectations and the availability and prices of different goods. The chapter uses the concept of elasticity to explain reactions in consumption decisions to price changes, but it does not go into detail about advanced concepts such as cross-price elasticity or income elasticity. In addition to the basics of demand theory, the chapter offers specific examples of consumer behavior and how they represent real-world proof of theoretical conclusions. The chapter is answers for the following questions: 1. How do we decide how much of a good to buy? 2. How does a change in price affect the quantity we purchase or the amount of money we spend on a good? 3. What factors other than price affect our consumption decisions? NEW TO THIS EDITION New headline on iTunes Music Store New headline on New York City cigarette tax Two new Questions for Discussion Two new Problems Living Econ on “Am I a Spendthrift?” Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 73 LECTURE LAUNCHERS Where should you start? 1. The beginning of this chapter is a partial review of chapter 3, Supply and Demand. This chapter focuses on the demand side of the market. Start your lecture by reemphasizing the determinants of demand. It is always useful to review what you have already covered in an earlier lecture. Ask students to cite examples of determinants from their own lives. The more often that examples relate to the students’ everyday life, the more likely they will understand the material. 2. A great launching point for the lectures on the demand for goods is to talk about how people spend their money. The Headline “Men vs. Women: How They Spend” on page 90 is a great place to begin this discussion. In addition, Figure 4.2 is also a great place to begin your discussion on The Demand for Goods. This article helps to illustrate that consumption patterns vary by gender, age, and other characteristics. 3. Ask students what happens to the satisfaction they get from each slice of pizza as they eat more and more pizza in a single night. All students will admit that eventually the additional satisfaction from each slice diminishes. This is a great way to introduce the concept of utility and marginal utility. 4. The most difficult topic within this chapter is that of elasticities. To begin students thinking about their responsiveness to a price change (price elasticity of demand), consider asking these questions. a. b. c. d. Ask students what they would do if tuition increased. Would they stay in school? If the price of textbooks required for classes increased, what would they do? Did everyone in the class purchase the text? The supplements? Why not? If the price was higher or lower, would this affect how many texts or supplements are purchased? Do students go to new movie releases or wait for the video? Do students go to the discount matinee show or do they go to see the show at night when the theater charges full price? The price of cigarettes has increased dramatically in the last few years. How has student’s consumption of cigarettes changed given these price changes? Use the Headlines “Higher Costs Would Deter Teen Smokers” and “Cigarette Smuggling: A Lesson in Elasticity” to illustrate this concept. Pay careful attention to the sections on elasticities. Students may have a natural feel for the concept of elasticities especially when examples such as cigarettes or high-status clothing are given as examples of products with inelastic demand curves. Students also have a feel for products with relatively elastic demand. For example, many students will quickly switch Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 74 consumption away from Pepsi if Coke, a substitute in consumption, is on sale. Estimates of elasticity for various goods and services are shown in Table 4.1 on page 96. COMMON STUDENT ERRORS Many students make these common errors. This same list is included in the student study guide. The first statement in each “common error” below is incorrect. Each incorrect statement is followed by a corrected version and an explanation. 1. The law of demand and the law of diminishing marginal utility are the same. WRONG! The law of demand and the law of diminishing marginal utility are not the same. RIGHT! Do not confuse utility and demand. Utility refers only to expected satisfaction. Demand refers to both preferences and the ability to pay. This distinction should help you to keep the law of diminishing marginal utility separate from the law of demand. 2. If marginal utility is diminishing, total utility is falling. WRONG! If marginal utility is diminishing, total utility could still be increasing! RIGHT! Marginal utility is the change in total utility when one more unit of a good or service is consumed. When marginal utility is declining, the consumer is said to have diminishing marginal utility. However, even if marginal utility is declining, but still positive, the consumer’s total utility is still increasing. 3. Figures 4.7a and 4.7b represent simple graphs drawn from a demand schedule. Figure 4.7a 3.5 Quantity Demanded 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 Price per Unit This Graph is Drawn WRONG! Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 75 Figure 4.7b 12 Price per Unit 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 Quantity Demanded This graph is drawn RIGHT! The first graph has been drawn without any units indicated and the axes are reversed. It is something of an accidental tradition in economics to show price on the y-axis and quantity on the x-axis. This convention is sometimes confusing to mathematicians, who want to treat quantity as a function of price, according to the definition in the text. In Figure 4.7a, the axes have been reversed and incorrect points have been chosen. Be careful! When you are drawing a new graph, pay special attention to the label for each axis and the units of measure used on each axis. If you are drawing a graph from a table (or schedule), you can usually determine what should be on the axes by looking at the heading above the column from which you are reading the numbers. Make sure price is shown on the y-axis (vertical) and quantity on the x-axis (horizontal). If you mix up the two, you may confuse a graph showing elastic demand with one showing inelastic demand. 4. The formula for the price elasticity of demand is: Change in Price Change in Quantity WRONG! The formula for the price elasticity of demand is: Percentage Change in Quantity Percentage Change in Price RIGHT! Do not confuse slope and elasticity. The wrong formula above shows the formula for calculating the slope of the demand curve. The correct formula above is used to calculate the price elasticity of demand. Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 76 The concept of elasticity allows us to compare relative changes in quantity and price without having to worry about the units in which they are measured. In order to do this, we compute percentage changes of both price and quantity. There is a causal relationship between price and quantity. A change in price causes people to change the quantity they demand in a given time period. By putting the quantity changes in the numerator, we can determine if the quantity response is very large in relation to a price change. If the quantity change is large, relative to the price change, then the demand is said to be elastic and |E| is relatively large. If the quantity response is small in relation to a price change, then demand is said to be inelastic and |E| is relatively small. Be Careful! Remember to take the absolute value of the elasticity when calculating the price elasticity of demand. The negative sign simply indicates the inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. 5. A flat demand curve has an elasticity of zero. A flat demand curve has an infinite elasticity. WRONG! RIGHT! When price remains constant, even when quantity demanded changes, the elasticity formula requires us to divide by a zero price change. In fact, as demand curves approach flatness, the elasticity becomes larger and larger. By agreement we say it is infinite. 6. The expectation that price will change in the future has the same effect as a change in the current price. WRONG! The expectation that price will change in the future shifts the demand curve, whereas a current price change is a movement along the demand curve. RIGHT! If prices are expected to rise in the near future, people will demand more of the commodity today in order to beat the rise in price. Demand increases and the quantity demanded will rise. However, if the price rises today, according to the law of demand, people will reduce their quantity demanded! Furthermore, demand itself does not change. A current price change and an expected price change have very different effects. HEADLINES In this chapter there are five Headline boxes. They deal with various aspects of the everyday reality of consumer demand. The titles of the pieces and the concepts they highlight are: “Men vs. Women: How They Spend” The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) concludes that mean and women spending patterns are different. Consumer patterns vary by gender, age, and other characteristics. Economists try to isolate the common influences on consumer behavior. “iTunes Music Store Hits Five Million Downloads” (Price Elasticity) Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 77 Ease of access to songs by title, artist or album, increased sales of portable digital music players, and an attractive price of 99 cents resulted in the download of five million songs in eight weeks in 2003. “Dramatic Rise in Teenage Smoking” (Price Elasticity of Demand) Smoking among youths in the United States rose precipitously staring in 1992 after declining for the previous 15 years. He prominent explanation for the rise in youth smoking over the 1990s was a sharp decline in cigarette prices in the early 1990s caused by a price war between the tobacco companies. The effectiveness of higher cigarette prices in curbing teen smoking depends on the price elasticity of demand. “Cigarette tax, highest in nation cuts sales by half” (Price elasticity) New York City smokers responded to a new $1.50 city tax(up from 8 cents), raising the price to $7.50 a pack, by reducing demand by 17 percent. It appears that smokers are going elsewhere to buy cigarettes, including nearby cities and online sites. ”Where the Pitch is Loudest” (Advertising) Shows countries where advertisers spend the most money per person. Switzerland spends the most per person followed by the U.S. The world average is $79 per person. ANNOTATED CONTENTS IN DETAIL I. Patterns of Consumption A. II. How Consumer Dollars Are Spent- (Figure 4.1) 1. 70% of household budgets are spent on housing, transportation and food. 2. ”Essential” items have changed from years ago. a. Cell phones b. DVD players Determinants of Demand - what determines what we buy? A. The Sociopsychiatric Explanation - The desire for goods and services arises from our needs for social acceptance, security, and ego gratification. 1. ”Keeping up with the Joneses” 2. Self preservation 3. Expressions of affluence (Figure 4.2) 4. Headline: “Men vs. Women: How They Spend” The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) concludes that mean and women spending patterns are different. Consumer patterns vary by gender, age, and other characteristics. Economists try to isolate the common influences on consumer behavior. B. The Economic Explanation - why we purchase goods. 1. Prices and income are just as relevant to consumption decisions as are more basic desires and preferences. 2. Demand Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 78 3. 4. 5. 6. C. Definition: Demand - The ability and willingness to buy specific quantities of a good at alternative prices in a given time period, ceteris paribus. Tastes - (desire for this and other goods) Example: If a study says ice cream is good for you, the demand for ice cream would increase. Income (of the consumer) Example: If you won the lottery you might buy more ice cream. The demand for ice cream would increase shifting the demand curve to the right. Expectations (for income, prices, tastes) Example: If you knew you were going to get rich soon you might deplete savings or borrow money to buy more ice cream now, increasing the demand for ice cream. Other goods (their availability and prices) Example: If the price of chocolate candy bars increased, you might buy ice cream instead of a candy bar, thus increasing the demand for ice cream. The number of consumers in the market. 7. 8. Market Demand Definition: Market Demand - The total quantities of a good or service people are willing and able to buy at alternative prices in a given time period; the sum of individual demands. III. The Demand Curve A. Utility Theory 1. The assumption that the more pleasure (utility) a product gives, the higher price one is willing to pay. Example: Students who like butter are willing to pay more for buttered popcorn than non-buttered popcorn because it offers more total utility. 2. Total vs. marginal utility (Figure 4.3) a. Utility Definition: Utility - The pleasure or satisfaction obtained from a good or service. b. Total Utility Definition: Total Utility - The amount of satisfaction obtained from entire consumption of a product. c. Marginal Utility Definition: Marginal Utility - The satisfaction obtained by consuming one additional (marginal) unit of a good or service. 3. Diminishing Marginal Utility a. The concepts of total and marginal utility explain not only why we buy popcorn at the movies but also why we stop eating it at some point. b. Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 79 Definition: Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility - The marginal utility of a good declines as more of it is consumed in a given time period. Example: Use the movie popcorn example. A student who enjoys popcorn finds out the price is free. When he consumes the first box, it is rewarding, the second box good, a third box decent, etc. After eating a sixth box, the student gets sick. Did the sixth box increase satisfaction? No, it had a negative marginal utility. (See the Cartoon about eating hamburgers on page 93.) i. So long as marginal utility is positive, total utility must be increasing. (Figure 4.3) ii. Additional quantities of a good yield increasingly smaller increments of satisfaction. (Figure 4.3) iii. Because the perception of satisfaction differs among individuals, an absolute measure of utility is not possible. However, since diminishing marginal utility is a common experience, it is a sufficient basis for our economic predictions of consumer behavior. B. IV. Price and Quantity - (Figure 4.4) 1. Demand is the relationship between price and quantity, 2. Ceteris paribus Definition: Ceteris paribus - The assumption that nothing else changes. 3. With given income, taste, expectations, and prices of other goods and services, people are willing to buy additional quantities of a good only it its price falls. 4. Law of demand Definition: Law of Demand - The quantity of a good demanded in a given time period increases as its price falls, ceteris paribus. 5. Demand curve Definition: Demand Curve - A curve describing the quantities of a good a consumer is willing and able to buy at alternative prices in a given time period, ceteris paribus. 6. As marginal utility declines, so does the willingness to pay. Price Elasticity A. Price Elasticity of Demand Definition: Price Elasticity of Demand - The percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price. 1. The response of consumers to a change in price is measured by the price elasticity of demand. 2. Formula: price elasticity ( E ) percentage change in quantity demanded percentage change in price Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 80 Example: 3. B. If the price of popcorn goes up 20% and the quantity of calculators demanded goes down 10%, the elasticity is 10% / 20% = -0.50. In this case, demand is relatively inelastic. Headline: “iTunes Music Store Hits Five Million Downloads” (Price Elasticity) Ease of access to songs by title, artist or album, increased sales of portable digital music players, and an attractive price of 99 cents resulted in the download of five million songs in eight weeks in 2003. Elastic vs. Inelastic Demand 1. Elastic a. The absolute value of “E” value is larger than 1. b. The Consumer is responsive to a change in price. c. Elasticity estimates (Table 4.1) 2. Note: Products that have elastic demands are airline travel, fresh fish and new cars. Inelastic a. The absolute value of ”E” value is less than 1. b. The Consumer is not very responsive to a change in price. Note: Products that have inelastic demand are cigarettes, gasoline and coffee. 3. 4. C. Unitary Elastic a. The absolute value of “E” is equal to 1. b. The percentage change in quantity demanded is equal to the percentage change in price. Headline: “Dramatic Rise in Teenage Smoking” (Price Elasticity of Demand) Smoking among youths in the United States rose precipitously staring in 1992 after declining for the previous 15 years. He prominent explanation for the rise in youth smoking over the 1990s was a sharp decline in cigarette prices in the early 1990s caused by a price war between the tobacco companies. The effectiveness of higher cigarette prices in curbing teen smoking depends on the price elasticity of demand. Price Elasticity and Total Revenue - (Figure 4.5 and Table 4.2) 1. The concept of price elasticity refutes the popular misconception that producers charge the “highest price possible.” 2. Total revenue Definition: Total Revenue - The price of a product multiplied by the quantity sold in a given time period: p x q Formula: total revenue price quantity sold 3. Price elasticity of demand and total revenue (Table 4.2) Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 81 a. b. c. D. V. Price cuts reduce total revenue if demand is price inelastic (|E|) < 1). Price cuts increase total revenue if demand is price elastic (|E|) > 1). Price cuts do not change total revenue if demand is unitary elastic (|E| = 1). Determinants of Elasticity 1. Necessities vs. Luxuries a. Some goods are so critical to our everyday life that we regard them as “necessities”. b. Demand for necessities is relatively inelastic. c. Examples of necessities are hairbrushes and toothpaste. d. A “luxury” good is something we’d like to have but aren’t likely to buy unless our income jumps or the price declines sharply. e. Examples of luxury goods include vacation travel, new cars, and HDTV sets. 2. The price elasticity of demand is influenced by all of the determinants of the demand curve. 3. Availability of substitutes – The greater the availability of substitutes, the higher the price elasticity of demand. 4. HEADLINE “Cigarette tax, highest in nation cuts sales by half” (Price elasticity) New York City smokers responded to a new $1.50 city tax(up from 8 cents), raising the price to $7.50 a pack, by reducing demand by 17 percent. It appears that smokers are going elsewhere to buy cigarettes, including nearby cities and online sites. 5. Relative Price - As price increases relative to income, |E| becomes larger. 6. Time - As time passes, more substitutes can be found or developed and |E| becomes larger. Policy Perspectives: Caveat Emptor A. - The Role of Advertising Caveat Emptor - Advertising campaigns are often designed to exploit our senses and lack of knowledge. B. Headline: ”Where the Pitch is Loudest” (Advertising) - Shows countries where advertisers spend the most money per person. Switzerland spends the most per person followed by the U.S. The world average is $79 per person. C. Are wants created? 1. Advertising is not the only reason consumption has increased, i.e. personality and social interaction dynamics have changed how much we consume. 2. A successful advertising campaign is one that shifts the demand curve to the right. (Figure 4.6) Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 82 IN-CLASS DEBATE, EXTENDING THE DEBATE, AND DEBATE PROJECTS In-class Debate Which products, if any, will have a perfectly inelastic demand? When a product has a relatively inelastic demand, a 10% rise in price would cause a decline in quantity demanded that is smaller in absolute value: for example, 8%. If the demand for a product were perfectly inelastic, a rise in price would have no effect on demand at all. For example, a 10% rise in price would cause a 0% decline in quantity. The demand curve for the product would be completely vertical. Here are some products that have relatively inelastic demand: a) gasoline (Think about the short run; ask yourself how consumers would respond to a price change in the first month), b) heroin, c) insulin, and d) light bulbs. Pick one of the products. How, if at all, could consumers adjust to a rise in the product’s price? Decide whether you think the product has perfectly inelastic demand. To say it another way, decide whether you think the demand curve will be vertical, or just quite steep? As you answer the question, remember that more substitutes for a product make the demand more elastic. Think about what might substitute for the product you pick. Be creative, realize that some substitutes are quite like the product they replace (tea is a hot beverage containing caffeine), but some are not (a letter might substitute for a telephone call). Extending the Debate Taxes to reduce teenage smoking? This chapter’s Headline, “Dramatic Rise in Teenage Smoking” (page 97) points out that the falling price for cigarettes during the mid-1990s caused an increase in teenage smoking whereas price hikes during the late 1990s led to a reduction in teenage smoking. As the article notes, the impact of rising and falling prices depends on the price elasticity of demand for cigarettes by teenagers, a statistic investigated by economist Jonathan Gruber Read the abstract of Gruber’s findings at: http://papers.nber.org/papers/w7780 and a nontechnical summary at http://www.nber.org/digest/oct00/w7780.html Should taxes be used to raise the price of cigarettes as a way to reduce teenage smoking? What are the strongest two arguments in favor of this proposition? What are the strongest two arguments against this proposition? Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 83 (Use price elasticity of demand for cigarettes by high school seniors as measured by Gruber in at least one of your arguments.) Teaching notes Classroom discussion often encourages students to debate one another. Although lively, such discussion usually involves a minority of students. A cooperative controversy ensures that every student is involved in the debate while using a relatively short period of class time. Moreover, it can help students see the arguments on both sides of an issue, often a difficult task for college students. Finally, the technique helps focus on an outcome such as identification of the strongest argument on each side. These outcomes may be useful later, if students are assigned an appropriate essay. Format: Organize students into groups of two. (Use instructor assignment or random assignment so that friends don’t work together.) One half of the groups take the pro side; the other half take the con side. Each pair lists the strongest arguments for their position. Then, pairs combine into groups of four, with one pair on each side of the debate. One pair reads their reasons while the other side listens. Then they reverse roles and repeat. Finally, each group of four selects the strongest argument on each side and, if appropriate, reaches a consensus on a final position. Debate project For related debate material see “Economic Growth” in Chapter 1. ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION, WEB ACTIVITIES AND PROBLEMS QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION 1. Why do people routinely stuff themselves at “all-you-can-eat-buffets”? Explain in terms of both utility and demand theories. The law of demand states that as the price of an item decreases a consumer will purchase more of a product. In this case, the cost of entry is the only price paid. Once paid, all additional trips to the buffet line have a price of zero. As a result, a consumer is making a rational choice to consume until the marginal utility of the last bite consumed is zero and equal to the price of the last item consumed. 2. What does the demand for education at your college look like? What is on each axis? Is the demand elastic or inelastic? How could you find out? A graph constructed for this problem would have tuition on the vertical axis and number of students who apply for college on the horizontal axis. The demand curve would look like most demand curves, sloping downward from left to right Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 84 in accordance with the Law of Demand. However, as the elasticity of the curve might vary from institution to institution and person to person, its location and shape would vary. To determine whether demand is elastic or inelastic, you could calculate the elasticity by finding out how enrollment responded when tuition last increased (keeping in mind the ceteris paribus assumption.) 3. What would happen to unit sales and total revenue for this textbook if the publisher reduced its price? According to the Law of Demand, as price goes down, quantity (unit sales) increases. What happens to total revenue, however, depends on the price elasticity of demand. In general, the price elasticity of demand for textbooks has an absolute value less than one. If that is the case, the percentage increase in quantity sold is less than the percentage decline in price and, as a result, the total revenue from sales would decline. In other words, the decrease in price more than offsets the increase in quantity and therefore total revenue (price times quantity) declines. 4. If all soda advertisement were banned, how would Pepsi sales be affected? How about total soda consumption? The main purpose of advertising is to increase demand. If all soda advertising were banned, then we would expect a decrease in demand resulting in both a decrease in sales for Pepsi and a decrease in total consumption of soda. 5. How has the Internet affected the elasticity of demand for air travel? The Internet has resulted in consumers having many more substitutes available. As a result the price elasticity of demand has increased. 6. Identify three goods each for which your demand is (a) elastic or (b) inelastic. What accounts for the difference of elasticity? Category (a) goods will include, in general, large budget items such as new cars or items with many substitutes, such as specific vacation sites and specific food items (chicken, beef, pork, etc.). Category (b) will most likely include small budget items such as table salt or items with few good substitutes such as gasoline and very broad categories of food (meat, vegetables, fruit, etc.) Elasticities can differ between products due to differences in prices relative to a consumer’s income, the number of substitutes available, and the length of the time to respond. 7. Utility companies routinely ask state commissions for permission to raise utility rates. What does this suggest about the price elasticity of demand? Why is demand so (in) elastic? When a price increase results in an increase in revenue, demand is relatively inelastic. Since utilities are asking for a rate (price) increase presumably to increase revenue, this suggests that the demand for gas, electricity, and local telephone service is inelastic. This inelasticity is generated by the fact that these services tend to be necessities, have few good substitutes, and, for some people, may be a relatively small portion of income. Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 85 8. Why is the demand for New York City cigarettes so much more price elastic than the overall market demand for cigarettes (See Headline, p. 100)? The price elasticity of demand for cigarettes in New York City is more elastic than that in the overall market because smokers can purchase cigarettes elsewhere. In general, the more substitutes, the greater the price elasticity of demand. 9. BuyMusic, a Windows-based music download site, was introduced in July 2003. How will that affect the demand for iTunes (see Headline, p. 95)? the price elasticity of demand? In the near term, the demand for iTunes will not be impacted very much, as so many people already own the necessary hardware, iPods, and they may not be willing to purchase new hardware to utilize BuyMusic’s service. Over a longer period of time, as current iPods become obsolete, consumers will face more choices of hardware and software. Because BuyMusic is a substitute for iTunes, the demand for iTunes could decrease (or not increase as much) and the price elasticity of demand for iTunes will become more elastic. WEB ACTIVITIES 1. Log on to http://www.whitehouse.gov/fsbr/income.html. Click on the chart for disposable personal income. Link into income and find the trend in real disposable personal income. Given the trend in this data, what has probably happened to consumer demand? Explain. Real disposable personal income has, in general, had an upward trend. Since disposable income is a determinant of demand, an increase in disposable income will generally result in an increase in consumer demand for most products. 2. Log on to www.msnbc.com. Complete a key word search using the search word consumer demand. Find an article that suggests a change in demand. a. Analyze the article and determine what determinants of demand are changing? b. What is the likely implication of this change on the market price? The answer to this question depends on the article found. Answers should center on an explanation of the determinants of demand and comparative equilibrium analysis. 3. Log on to http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/popproj.htmland click on “Total Resident Population”. What are the high and low projections for the U.S. population now compared to the year 2025? What is the likely impact on the demand for housing in the U.S.? Explain. What implication does this have for the price of housing? The high projection for population in the U.S. for 2025 is 380,397,000 and the low projection is 308,229,000. This compares to a current population of around 282 million. In either case, the population is significantly higher than current estimates. Since the number of buyers is one of the determinants of demand, the demand for housing will continue to increase. It is not possible, however, to determine what will happen to the market price of housing. Although the increase in population will have a tendency to drive the price of housing up, we cannot tell from the available information Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 86 what will happen to supply. Using the ceteris paribus assumption, if we assume only population changes, the price of housing would increase due to the increased demand. 4. Log on to http://www.bls.gov/cex/. Click the overview button, then click on "News Release" and thenthe link for "Consumer Expenditures." a. What has happened to consumer income before taxes in the last three years reported? b. What has happened to the average expenditures for food purchased away from home as a percentage of income before taxes? What are some possible explanations for this trend? c. What two categories of expenditures have had the largest percentage increase in the last two reported years? The answer to this question depends upon the year in which the question is answered. In the year 2001 survey, the consumer income before taxes increased in the years 1999, 2000 and 2001, expenditures for food purchased increased by a larger percentage than the income increases, and the two largest percentage changes were personal insurance and pensions and spending on health care. PROBLEMS 1. The following is a demand schedule for shoes: Price (Per Pair) $100 $80 Quantity Demanded a. 10 14 $60 $40 $20 18 22 26 Illustrate the demand curve on a graph. Demand for Shoes 120 Price - per shoe 100 80 60 40 20 D2 D1 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 Quantityof Shoes (pairs per year) Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 87 30 35 b. How much will consumers spend on shoes at the price (i) $80 and (ii) $60? As the price drops from $80 to $60 a pair, is demand elastic or inelastic? (i) $1,120, which is 14 pairs x $80 per pair. (ii) $1,080, which is 18 pairs x $60 per pair. The quantity demand increases from 14 to 18, a change of 25% (using the midpoint formula), as the price drops from $80 to $60, a change of 28.5%. This gives an elasticity of .25 / .285 = .88. (Remember, price elasticity = % change in quantity demanded / % change in price.) The demand is slightly inelastic as the price changes over this range. We also know that demand for shoes is considered to be inelastic, because as price falls, total revenue decreases. c. If advertisers convinced people that to be stylish they needed more shoes, how would the demand curve be altered? Illustrate this change. If advertisers successfully convinced people that they needed more shoes, the demand curve would shift to the right and may also become less elastic. This is illustrated on the graph above and is labeled D2. 2. According to the elasticity computation on p. 96, by how much would popcorn sales fall if the price increased by 20 percent? By 50 percent? If the price elasticity of demand for popcorn is 0.50, and price increased by 20%, then : percentage change in quantity demanded X 0.50 , thus X = 10 percent. percentage change in price 20 If the price elasticity of demand for popcorn is 0.50, and price increased by 50%, then: percentage change in quantity demanded X 0.50 , thus X = 25% percent 50 percentage change in price 3. According to Table 4.1, by how much will unit sales of (a) coffee, (b) shoes, and (c) airline travel decline when price goes up by 10 percent? What will happen to total revenue in each case? (a) The quantity demanded of coffee will decline by 3% and total revenue will increase. (b) The quantity demanded of shoes will decline by 9% and total revenue stay about the same. (c) The quantity demanded of airline travel will decline by 24% and total revenue will decrease. 4. According to the Headline on p. 62 (in Chapter 3), what is the price elasticity of demand for alcohol among college students? Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 88 The article states that the quantity demanded will decrease by 33% when price goes up $1.00. You calculate the percentage change in price by taking the change in price, $1.00, and dividing it by $2.67 (the average of the starting and ending prices). This is equal to 37%. The price elasticity is 33% divided by 37%, which results in an elasticity of 0.89. This is slightly inelastic. 5. According to Table 4.1, by how much would coffee sales decline if the price of coffee doubled? If Starbucks doubled its coffee prices, what would happen to Starbucks' sales? How do you explain these responses? According to table 4.1, coffee has a price elasticity of demand of 0.30. As a result, if the price of coffee doubled (a 100 percent increase in price) the quantity demanded would change by 0.30 times that amount or a decline of 30 percent. X percentage change in quantity demanded 0.30 , thus X = 30 percent. percentage change in price 100 If Starbucks doubled its price, while all other firms kept their price the same, their sales would fall by much more than 30 percent. The response would be much larger in this case because there are many substitutes to Starbucks’ coffee. If only Starbucks changed its price, people would switch to substitutes and sales for Starbucks would fall substantially. If all firms doubled their prices, the relative prices would remain unchanged and there would be little incentive to switch product names. Nonetheless, consumers would respond by consuming less coffee in total. 6. In 1998, President Clinton proposed an additional $1.10 per pack tax that would have increased cigarette prices roughly 60 percent. According to the Headline on p. 97, by how much would teen smoking have dropped in response to such a tax? Elasticity of demand = 0.7 = % Qd / 0.60 = 0.60 x 0.7 = 0.42 The quantity demanded of cigarettes by teens would decrease by 42 percent given a $1.10 per pack tax on cigarettes. 7. Suppose the following table reflects the total satisfaction (utility) derived from eating pizza: Quantity (slice) Total Utility 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 47 92 122 135 137 120 70 a. b. What is the marginal utility of each pizza? What causes the marginal utility to diminish? (a) first slice , MU = 47 second slice, MU = 45 (92-47) third slice, MU = 30 (122-92) Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 89 fourth slice, MU = 13 (135-122) fifth slice, MU = 2 (137-135) sixth slice, MU = -17 (120-137) seventh slice, MU = -50 (70-120) (b) 8. Economists have found that after some point, the more you have of something, the less valuable each additional unit. After the first slice of pizza, the initial good feeling decreases. While the second slice is still very enjoyable, it is not as good as the first slice. The same pattern continues until we get to the sixth slice, which actually makes you feel stuffed and uncomfortable, resulting in a decrease of additional satisfaction. The situation worsens with the seventh slice. Economists estimate price elasticities by using average price and quantity to compute percentage changes. Thus, Q1 Q2 Q1 Q2 2 E P1 P2 P1 P2 2 Using this formula, a. Compute E for a popcorn price increase from 20 cents to 40 cents per ounce (Figure 4.5) b. Compute E for New York City cigarettes (see Headline, p. 100 and text) a. 16 4 12 16 4 1.2 2 E 10 1.8 and |E| = 1.8 0.20 0.40 0.20 0.666 0.20 0.40 0.30 2 b. 1563 2922 1563 2933 .61 2 E 2.9 and |E| = 2.9 7.50 6.08 .21 7.50 6.08 2 Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 90 MEDIA EXERCISE Chapter 4 Consumer Demand Name: ___________________ Section: __________________ Grade: ___________________ Find an article that describes either a movement along a demand curve or a shift of a demand curve. Use the article you have found to fulfill the following instructions and questions: 1. Mount a copy (do not cut up newspapers or magazines) of the article on a letter-sized page or print an article from an Internet news agency such as www.cnn.com, www.msnbc.com, www.abc.com, www.nytimes.com, etc. 2. Find an example in the article of one (and not more than one) of the following four possible shifts of supply or demand: Leftward (downward) shift of the demand curve. Rightward (upward) shift of the demand curve. Movement up along the demand curve. Movement down along the demand curve. Write below your article the shift of demand or movement along the demand curve that is best represented in the article. The shift or movement may already have occurred, may be occurring currently, or may occur in the future. 3. Use an arrow in the article to indicate the product or product market in which the shift or movement occurs. 4. Underline the single sentence (not more than a sentence) that describes the change in the determinant of demand or price that has caused the shift you chose in number 2 above. 5. Draw brackets around the word or phrase (not more than a sentence) that indicates the buyer through whom the change in the determinant of demand or price initially affects the market, ceteris paribus. 6. Circle the single sentence (not more than a sentence) that indicates a change in price or quantity that results from the shift in demand or a change in price. (Hint: Make sure the changes are consistent with the shift you chose in number 2 above. If a supply determinant has changed or the article shows that the seller has changed quantity or price, then you should be indicating a movement along the demand curve, not a shift.) 7. In the remaining space below your article, indicate the source (name of newspaper, magazine, or web site), title (newspaper headline, magazine article, or web article title), date, and page for the article you have chosen. Use this format: Source: _____________________ Date: ______________ Page: _____________ Title: ___________________________________________________________ If this information also appears in the article itself, circle each item. 8. Neatness counts. Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 91 Professor's Note Learning Objective for Media Exercise To enable students to distinguish between shifts in the demand curve and movements along the demand curve, to get students to recognize immediately any demand determinants in the news, and to familiarize students with other sources of information that give clues to the effects on demand. Suggestions for Correcting Media Exercise 1. 2. 3. Check for consistency between the shift chosen in number 2 and the circled part of the article indicating the direction of change in price or quantity. Check for consistency between the shift chosen in number 2 and the underlined portion of the article indicating a determinant of demand or the price of the good itself. The chosen market may be incorrect for the determinant being considered. Likely Student Mistakes and Lecture Opportunities 1. 2. 3. Typically, students will find supply shifts or supply determinants. This is a useful opportunity to distinguish between the buyer and the seller in a transaction and to reiterate the difference between supply and demand. Students tend to be thinking primarily in terms of absolute rather than relative prices early in the semester. So in some markets students will find a change in a determinant that suggests prices will fall, but prices will rise, say, 1 percent. The point is that, relative to other prices and an inflation of perhaps 3 percent per year, relative price of such a good has fallen. Vertical relationships often confuse the students. For example, automation is a technological change that students will think of as a supply determinant. However, they will choose the labor market because the article will talk about employees being laid off. The students will show a supply shift rather than a derived demand shift. Such mistakes provide an opportunity to distinguish between vertical and horizontal relationships among products. SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES Barnett, F. William: "Four Steps to Forecast Total Market Demand," Harvard Business Review, July-August 1988, pp. 28-38. Provides an easily readable, practical guide to estimation of the demand curve, with an example of the copier paper market. Gruber, Jonathan: “Tobacco At the Crossroads: The Past and Future of Smoking Regulation in the United States” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Spring 2001, pp. 193-212. Kass, Leon R.: "Organs for Sale? Propriety, Property, and the Price of Progress," Public Interest, Spring 1992, pp. 65-86. Chapter 4 – Consumer Demand – Page 92