* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download What has changed in Geography? Geography 2014 Curriculum

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

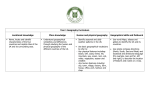

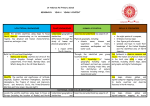

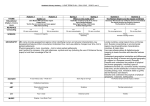

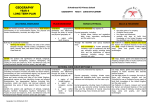

Leanne Reeves – Baldwins Gate Primary School What has changed in Geography? Geography 2014 Curriculum This is a new approach to a national curriculum document. It is concise and sets out only the core knowledge that students should acquire. It does not specify approaches to teaching, nor explain how to put the content into a teaching and learning sequence. There is renewed emphasis on location and place knowledge, human and physical processes and some technical procedures, such as using grid references. There is a renewed commitment to fieldwork and the use of maps, as well as written communication. The Level Descriptors which made up the Attainment Target have been removed. Schools are free to devise their own curriculum and assessment system. Selecting localities The programmes of study refer to areas of different scales and some specific places such as North and South America. A local scale study is the area in which people live their everyday lives. For school pupils this usually encompasses where they live, go to school and play. It may also include places they visit with parents on a regular basis to shop or visit relatives for example. In contrast, a geographical region is generally a large area of land with distinguishing geographical, ecological, cultural or political characteristics that set it apart from other areas and may exist within one country or be spread over several. You may have always taught a study of India or a country in Africa at KS2 and you could still continue to teach these localities even though the Americas are statutory. At KS1 you can teach about any contrasting non - European country. At KS2 you are also required to teach about resources, such as food, energy, and trade links; and key aspects of physical geography such as rivers, mountains, volcanoes and climate zones. These aspects could be done through studies in whatever countries you feel are appropriate. In addition, remember this is a core entitlement curriculum and you can supplement it with whatever you wish. The Americas are a vast place to teach about. Start by developing pupils' core knowledge e.g. knowing the location and names of the North and South American continents and their make up in terms of countries, regions, key cities and physical features. Then, drawing on the idea of a 'zoom lens' study places in more depth, making comparisons between them. For example, you might go on to study the significance of the Amazon rainforest or the topicality of Brazil and look at specific places within those regions at a local scale. Fieldwork Fieldwork is a valuable aspect of geography that helps to motivate pupils and also raises standards of attainment. It is statutory for all key stages and ideally should be done at least once in every year by every year group. Key stage one might focus on the school grounds and the immediate locality of the school, i.e. what can be reached by walking, whereas key stage two pupils would Leanne Reeves – Baldwins Gate Primary School investigate the wider locality in which they live. Pupils from different year groups might visit the same place, for example the local High Street, but adopt a different focus or enquiry. What should the geography curriculum look like? The National Curriculum sets out ‘the core knowledge and understanding that all pupils should be expected to acquire in the course of their schooling', but a core curriculum is not all that students should be taught. A local and personalised element to the curriculum is essential to ensure that pupils are engaged with innovative and enjoyable learning that has relevance to their lives and work while challenging them to think about 'real world' issues. The diagram below shows the relationship between the subject core and the curriculum taught in two different schools: The main function of the Programmes of Study for geography is to guide teachers in the selection of what to teach: they do not provide guidance on how to teach. For example, they make no reference to enquiry learning approaches, which are widely recognised as effective in geography. Values, attitudes and pupil capabilities (competences) are similarly omitted. Teachers should be guided by their knowledge of pupils' needs and interests when selecting appropriate subject content and develop this into challenging and relevant teaching experiences using their professional skills. Use the ethnic diversity and personal geographies that pupils bring to school to enhance and develop your curriculum. Similarly, draw on the interests, backgrounds and experiences of staff. Add into this the contexts provided by real local and global issues to ensure the curriculum is full of lively and relevant, contemporary content. Leanne Reeves – Baldwins Gate Primary School Overview Places and locations Location knowledge has a prominent place in the new curriculum: At key stage 1 pupils are expected to name and locate the world’s continents and oceans and the countries and capital cities of the United Kingdom. At key stage 2 pupils are expected to locate the world’s countries, identify the position and significance of latitude and longitude. They also should be able to name and locate cities of the United Kingdom. Children develop useful mental maps and locational knowledge when: they are involved in investigations in their school’s grounds and local area, using ground and aerial photographs with maps to locate features, and drawing maps, as integral in their studies. This facilitates discussion of locations, links and area; from Year 1, they recognise maps of the British Isles, with its countries, and the basic features on the world map, its continents and oceans, and have handled globes and looked in atlases; pupils take a Barnaby Bear away on a holiday or for a weekend at home to photograph and track sites and routes they visit or use and share this experience and their knowledge, including their maps and diaries, with other children; their studies of topics and places are set in real places, enabling them to develop their knowledge of places nationally, in Europe and globally using globes and atlas and wall maps, helping them to be able to name and locate major events and places and key map features, such as the Equator; teachers have an informed locational knowledge, and are able to help children locate places locally, nationally and globally using their own knowledge and helping the children use globes, atlases and maps to find places and talk about what is there; teachers ensure up-to-date appropriate maps, atlases and globes, and web-based and other ICT map sources, are regularly accessible for children to search and use; pupil’s knowledge about the world is noted as an aspect of their attainment. To help pupils in key stages 1 and 2 develop their locational knowledge and mental mapping skills, you need to have an effectively developed locational knowledge framework of your familiar places, of the UK and of the world. You must understand the terms locational knowledge and mental map, and Leanne Reeves – Baldwins Gate Primary School know a variety of ways to help children develop their own mental maps of their neighbourhood and city/region, and of their country, continent and the world, so that they develop the ability to recall, name and locate on maps specified/studied places, human and physical features and events. Active, investigative and practical approaches are key to developing children’s local and world locational knowledge. These teaching ideas can be adapted to be age appropriate. Draw a sketch maps to show locations and routes such as the route to school or the area around home. An alternative is to make a model with scrap materials or using toy buildings, vegetation and roads. This activity is a good basis for discussing how we know what to include and how we link sites and routes. What is included and what not? Why is this? Consider the extent of the local mental map and how to might enhance it, say, for another person to use. This links well with local explorations and fieldwork. When investigating the local area, use street maps, Google Earth and maps, OS maps and other sources – such as a map you have drawn – to view and explore the area. Discuss who knows what about the area, and how they acquired this knowledge. Mark a suitable map or model with features, sites, events and places of interest/value/fear. Talk about how shared these are these and why they are included. Can a shared map or model be agreed? On what grounds? Why is it helpful to know where places are, locally and globally? Which would be on your map? What places have pupils heard about? Do they know where they are? Use maps, globes and atlases to find out or check. Add in some other places to find; talk about why you have referred to them. Have a wall map of the British Isles or the world on a wall in the classroom. Mark places on it. Ask the children where this is. Ask why you have put it up. Encourage children to add places and features they can justify (they have heard of it; it’s in the news; they have been there; they like it…). Follow a journey around the world, or create one, adding to it daily or weekly: Where is it going? Why there? What means of transport is used? Locally, in the UK, Europe or the world, which places are significant? Discuss what the term ‘significant’ means. Why and how can it be used about places, features and locatable events. Consider examples and justify or contend their significance. Introduce or keep using a globe and an atlas. A new atlas should be able to be skimmed through, children being given time to see what it contains and to ask questions. Regularly use globes and atlases. Look up places and begin to use the contents and index pages. Select particular maps: what is shown on the map? How is it shown? Why is that? What do they think is missed out? Why? Become used to using globes and atlases to locate places and features and to say something about what they might be like. Undertake a Google search for images of these places and features: What do they actually look like? Are different features, e.g. cities, rivers or mountains, depicted in the same way on different maps in the atlas? What do we learn about using symbols and keys? What are the grid lines for (latitude and longitude)? How can we work out how far it is from one place to another? Why would we go there? How would we get there? In studies of places and aspects of human/physical geography, always check the locations of places using globes and atlas maps. It is useful to have access to a detailed world atlas, such Leanne Reeves – Baldwins Gate Primary School as The Times Atlas of the World. From time to time check how well everyone knows these locations and how they enhance personal knowledge of the world. You might have a quiz, set a task to make a British Isles or world map locating places and using symbols, or play a card game with the names of countries on cards to be placed in turn on the correct continent (accurately if possible) on a world map.