* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download chap_03

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

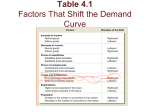

Chapter 3. Demand Theory and Analysis Topics to Be Discussed n Market Mechanism (Demand & Supply) n n n n - Definition - Factors Affecting D & S. Individual / Market Demand - Relationship between Individual D. and Market D. Shifts in Supply and Demand Elasticities of Demand (Price, Income and Cross) Appendix - Consumer Preference - Indifference Curve and Budget Constraints - Utility Maximization. The Market Mechanism n Supply • Measures how much producers are willing to sell for each price they receive in the market • This price-quantity relationship can be shown by the equation: Qs QS (P ) n Demand • Measures how much consumers are willing to buy for each price per unit. • This price-quantity relationship can be shown by the equation: QD QD (P) CHAPTER 3 1 The Market Mechanism n Characteristics of the equilibrium or market clearing price: • QD = QS • No shortage • No excess supply • No pressure on the price to change CHAPTER 3 2 The Market Mechanism n If the market price is above equilibrium: • There is excess supply • Producers lower prices • Quantity demanded increases and quantity supplied decreases • The market continues to adjust until the equilibrium price is reached n If the market price is BELOW equilibrium: ???? CHAPTER 3 3 The Market Mechanism n Market Mechanism Summary 1) Supply and demand interact to determine the market-clearing price. 2) When not in equilibrium, the market will adjust to alleviate a shortage or surplus and return the market to equilibrium. 3) Markets must be competitive for the mechanism to be efficient. Shifts in Supply and Demand n n Equilibrium prices are determined by the relative level of supply and demand. n Changes in any one or combination of these variables can cause a change in the equilibrium price and/or quantity. Supply and demand are determined by particular values of supply and demand determining variables. Shifts in Supply and Demand n Non-price Determining Variables of Supply • Costs of Production – Labor – Capital – Raw Materials CHAPTER 3 4 Shift in Supply n Given the model shown, assume the cost of raw materials falls. n Supply Response: • At P1 producers now put Q3 on the market. • At P2 producers now put Q2 on the market. • These changes yield a new supply curve. • The movement of the supply curve to the right from S to S’ is an increase in supply. • The new supply curve shows that more will be produced at a given price or a lower price will be required for a given quantity. • Producers can now produce more for given cost outlay or earn higher profit at a given market price. • In either case, more is produced at a given price and supply increases. CHAPTER 3 5 Shifts in Supply n Supply • Supply is determined by non-price supply-determining variables as such as the cost of labor, capital, and raw materials. • Changes in supply are shown by shifting the entire supply curve. • Changes in quantity supplied are shown by movements along the supply curve and are caused by a change in the price of the product. Shifts in Demand n Non-price Determining Variables of Demand • Income, Consumer Tastes, Price of Related Goods Decrease in Demand n If demand decreases by 40%, how can we express the new demand curve? Shifts in Supply and Demand n When supply and demand change simultaneously, the impact on the equilibrium price and quantity is determined by: 1) The relative size and direction of the change 2) The shape of the supply and demand models Elasticities of Supply and Demand n n n Generally, elasticity is a measure of the sensitivity of one variable to another. It is the percentage change in one variable in response to a one percent change in another variable. Price elasticity of demand measures the sensitivity of quantity demanded to price changes. • It measures the percentage change in the quantity demanded for a good or service that results from a one percent change in the price. EP (% Q)/(% P) Q/Q P Q P/P Q P n Interpreting Price Elasticity Values 1) Because of the negative relationship between P and Q, EP is negative. 2) If EP > 1, the percent change in quantity is greater than the percent change in price. We say the demand is price elastic. 3) If EP < 1, the percent change in quantity is less than the percent change in price. We say the demand is price inelastic. n The primary determinant of price elasticity of demand is the availability of substitutes. • Many substitutes demand is price elastic • Few substitutes demand is price inelastic Linear Demand Curve CHAPTER 3 6 Infinitely Elastic Demand : Horizontal Line Completely Inelastic Demand : Vertical Line Elasticities of Supply and Demand CHAPTER 3 7 n Income elasticity of demand measures the percentage change in quantity demanded resulting from a one percent change in income. n The income elasticity of demand is: n Cross elasticity of demand measures the percentage change in the quantity demanded of one good that results from a one percent change in the price of another good. n n For example consider the substitute goods butter and margarine. n EI Q/Q I Q I/I Q I The cross elasticity for substitutes is positive, while that for complements is negative. The cross elasticity of demand is: EQbPm Qb/Qb Pm Qb Pm/Pm Qb Pm Short-Run Versus Long-Run Elasticities n n Price elasticity of demand varies with the amount of time consumers have to respond to a price. n Other Goods (durables): • Short-run price elasticity is greater than long-run elasticity (e.g. automobiles) Most goods and services: • Short-run price elasticity is less than long-run elasticity. (e.g. gasoline) Fitting Linear Supply and Demand Curves to Data Problem Solving. n Let’s begin with the equations for supply and demand: Demand: Q = a + bP Supply: Q = c + dP n n We must algebraically solve for a, b, c, and d. n n Derive the supply and demand for a product under following information. • The relevant data are: – Q* = 7.5 pound/yr. P* = 75 cents/pound – ES = 1.6 ED = -0.8 Supply : Q* = -4.5 + 16P* Demand : Q* = 13.5 - 8P* CHAPTER 3 8 EXAMPLE n n n We have written supply and demand so that they only depend upon price. n We know the following information regarding the copper industry: • I = 1.0 • P* = 0.75 • Q* = 7.5 • b=8 • Income elasticity: E = 1.3 n n f can be found by substituting known values into the income elasticity formula: n Solving for a gives: Q* = a - bP* + fI 7.5 = a - 8(0.75) + 9.75(1.0) a = 3.75 Demand could also depend upon income. Demand would then be written as: Q = a - bP + fI • I is aggregate income or GDP. Solving for f gives: 1.3 = (1.0/7.5)f f = (1.3)(7.5)/1.0 = 9.75 Point versus Arc Elasticity n n Problem in Point Elasticity Arc Elasticity : Use the midpoint Individual versus MKT. Demand n n Market Demand = Sum of Indiv. Demand. Q(market) = Q(indiv.1) + Q(indiv.2) + …. CHAPTER 3 9 Consumer Preferences (APPENDIX) n Three Basic Assumptions 1) Preferences are complete. 2) Preferences are transitive. 3) Consumers always prefer more of any good to less. Indifference Curves • Indifference curves represent all combinations of market baskets that provide the same level of satisfaction to a person. CHAPTER 3 10 Indifference Curves • Indifference curves slope downward to the right. – If it sloped upward it would violate the assumption that more is preferred to less. • Any market basket lying above and to the right of an indifference curve is preferred to any market basket that lies on the indifference curve. • Indifference curves cannot cross. -This would violate the assumption that more is preferred to less • Along an indifference curve there is a diminishing marginal rate of substitution. – Note the MRS for AB was 6, while that for DE was 2. Consumer Preferences n The Marginal Rate of Substitution • • The marginal rate of substitution quantifies the amount of one good a consumer will give up to obtain more of another good. It is measured by the slope of the indifference curve. CHAPTER 3 11 Perfect Substitutes and Complements Two goods are perfect substitutes when the marginal rate of substitution of one good for the other is constant. Two goods are perfect complements when the indifference curves for the goods are shaped as right angles [L-shape] Budget Constraints n Preferences do not explain all of consumer behavior. n Budget constraints also limit an individual’s ability to consume in light of the prices they must pay for various goods and services. n The Budget Line • The budget line indicates all combinations of two commodities for which total money spent equals total income. Budget Constraints n The Budget Line • • Let F equal the amount of food purchased, and C is the amount of clothing. Then PFF is the amount of money spent on food, and PCC is the amount of money spent on clothing. • The budget line then can be written: PFF PCC I n The Effects of Changes in Income and Prices • • Price Changes – If the price of one good increases, the budget line shifts inward, pivoting from the other good’s intercept. – If the price of one good decreases, the budget line shifts outward, pivoting from the other good’s intercept. Price Changes – If the two goods increase in price, but the ratio of the two prices is unchanged, the slope will not change. (i.e., Parallel Shift) – However, the budget line will shift inward to a point parallel to the original budget line. Consumer Choice n Recall, the slope of an indifference curve is: n Further, the slope of the budget line is: MRS Slope C F PF PC n Therefore, it can be said that satisfaction is maximized where: CHAPTER 3 MRS PF PC 12 Maximizing Consumer Satisfaction CHAPTER 3 13 The Concept of Utility n Utility and Satisfaction • • Utility is the level of satisfaction that a person gets from consuming a good or undertaking an activity. U=f (Food, Clothing) If a person is happier if they buy 2 movies instead of 1 golf game, it can be said that the person received more utility from 2 movies than the 1 golf game. n Utility and Satisfaction • • A utility function is obtained by attaching a number to each market basket. A utility function illustrating the satisfaction derived from food and clothing may be written: n Marginal Utility • • Marginal utility measures the additional satisfaction obtained from consuming an additional amount of a good. The principle of diminishing marginal utility states that as more and more of a good is consumed, consuming additional amounts will yield smaller and smaller additions to utility. n Marginal Utility • If consumption moves along an indifference curve, the additional utility derived from the consumption of more of one good must balance the loss of utility from the decrease in consumption in the other. • Therefore, we can say that 0 MUF(F ) MUC(C ) n Which equates to: (C/F ) MUF/MU C) n Substituting MRS for the first part of the equation gives: MRS MUF/MUC) PF / PC CHAPTER 3 14