* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Markets Manual

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

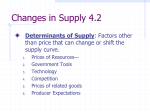

Markets Manual Purpose of the Program This program allows you to manipulate a perfectly competitive market in a number of ways. In the process you can observe some of the ways this type of market reacts to assorted disturbances. The program also allows you to interfere with the market, as governments often do, and to observe the consequences of your interference. This should allow you to draw some conclusions about the usefulness of such interventions. The Basic Model The market you are about to disturb is the market for wheat. If people like you don't get in the way, this comes very close to the economist's definition of a "perfectly competitive market." Below is a comparison of the requirements of "perfect competition" and the facts about the wheat market. Perfect Competition Wheat Market An infinite number of sellers (firms Tens of thousands of farms in the U.S., many or individuals) more in other countries An infinite number of buyers Millions of buyers (but there are a few large firms that buy large amounts of the wheat produced in the U.S.) Perfect free information about prices Every seller produces exactly the same product ad all potential buyers know that the products are identical. Information is very cheap and easy to get. Free entry into the industry (no special start up costs), and free exit, no special costs for leaving the industry. There are entry and exit costs, but they are not very large. Farmers borrow large amounts to start up, but the security is mostly the land and equipment bought, so it isn’t too hard or expensive to borrow. There are a number of different varieties of wheat, but within each variety, it doesn’t matter which farm it was grown on. Supply Suppliers—those prepared (if conditions are right) to sell a given product in this market—are assumed to be business firms. The suppliers, wheat farmers in this module, are assumed to be motivated by only one thing: profit. Ignoring all sorts of potential complexities, profit is defined as the total revenues of the firm minus the total costs of the firm. The amount of product that any firm is willing to sell depends on two things: the price of the product and the firm’s costs. Due to the special conditions of the perfectly competitive model the firm considers the price of the product to be a fixed value -- totally out of its control. The firm’s costs depend on how much it produces. The costs also depend on technology, resource prices, laws, and other matters, but those will be considered constant here. In the short term firms are unable to change many of the resources they use in production—they can neither increase nor decrease the amount used. Example: the size of the building they have as a production facility. As a result, they are subject to the Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns. If they try to increase production, they add more and more of the resources they can control to the fixed amounts of the ones they cannot control. The result is that increasing production increases the cost of producing additional units. This can be seen from the following example: Current production = 100 Adding 1 more unit takes 10 more hours of labor, each hour costs $10, the added unit costs $100 Current production =101 Adding 1 more unit takes 11 more hours of labor, each hour costs $10, the added unit costs $110 Current production =102 Adding 1 more unit takes 12 more hours of labor, each hour costs $10, the added unit costs $120 Holding constant all the other things that might affect the firm’s costs and production, the result is a Supply Curve as in Figure 1 below. A firm’s supply curve is defined as the line showing the quantity a firm is willing to produce at each possible price. The larger the quantity to be produced, the higher the unit cost of the extra unit and the higher the price required to cover that cost. No firm (just interested in profit) will be willing to supply a unit of the product that costs it $120 to produce if the price it expects to sell the unit for is less than $120. On the supply curve, therefore, the Law of Supply shows that the higher the price, the larger the quantity the firm is willing to produce. That is why the supply curve slopes upward. 2 Figure 1 The Supply Curve Influences other than the price of the product can change the quantity supplied at a given price. If something makes it cost less to add units to production, then the supply curve moves away from the vertical axis. (This is referred to as an “increase in supply”.) If something makes it more costly to add to production, the supply curve moves toward the vertical axis. (This is referred to as a “decrease in supply”.) (See Figure 2.) The above describes supply by a single firm. The behavior of the (“infinite”) number of firms in the market is just like the supply by a single firm, only the quantities are larger. Figure 2 The Supply Curve The quantity of wheat supplied at all possible prices is described by the supply curve. It can also be presented with either an equation or a graph. For the wheat market, the equation for wheat supply is: Qs = ( - 1000 + 700(Rain) + 50(Wheat Price)) * (# of Farms/Seed Cost) 3 Qs is the quantity of wheat supplied. It is positively affected by the price of wheat (the higher the price, the more wheat sold). Qs is positively related to the amount of rain that falls on farms (measured relative to an average year), positively related to the price of wheat, negatively related to seed cost, and positively related to the number of farms. If the amount of rainfall is 10 inches, seed cost is $10 per bushel, and the number of farms is 1,000, then the supply curve looks like Figure 3. (The price of $17.33 and the quantity of 60350, define one point on the supply curve.) Figure 3 The Supply of Wheat Demand Every individual in the market has to decide how much to buy of this product, and even whether to buy it. At a given price for this product, the decision for a single person is going to be based on three basic things: (1) the opportunity cost of buying the product; (2) the real income of the person; and (3) the preferences (tastes) of the person. The opportunity cost is a matter of considering three types of prices. There is the price of the product itself, the prices of goods that are substitutes for this product, and the prices of goods that are complements to this product. Suppose the product is ice cream and its price is $2 per gallon. A substitute for ice cream is frozen yogurt, suppose its price is $1.50 per gallon. Ignoring complements for the moment, the opportunity cost of buying a gallon of ice cream is that the $2 spent on that is $2 less that can be spent on frozen yogurt. The “opportunity cost” of the gallon of ice cream is 1.33 gallons of yogurt that you now cannot buy. If the price of yogurt were $2 then the opportunity cost of buying ice cream drops to 1 gallon of yogurt. That encourages people to buy more ice cream. A complement to ice cream is chocolate syrup. Suppose the “typical” buyer in the market likes a pint of chocolate syrup with an average gallon of ice cream, and the price of syrup is $1 a pint. The decision to buy the ice cream is conjoined with the decision to buy the syrup. Now the overall cost is really going to be $3, and the opportunity cost (if syrup and ice cream are not 4 consumed together) of buying the ice cream is now—at a yogurt price of $1.50—two gallons of yogurt. If the price of syrup went to $2 a pint, the opportunity cost of ice cream/syrup would go to 2.66 gallons of yogurt ($4 for the combo, versus $1.50 for the yogurt). This would discourage the purchase of ice cream. How much ice cream a person buys depends on how much real income the person has. Obviously, if your income is such that at an ice cream price of $2 a gallon you would spend all your income for a week buying one gallon—you are not going to be buying two gallons a week. That’s true even if the ice cream was all there was in the world that you ever wanted. Overall, the lower your real income, the less you’ll buy. There are exceptions to this rule, but ice cream isn’t one of them. If the price of ice cream goes up, the opportunity cost of ice cream goes up, the buyer’s real income goes down and for both reasons the amount of ice cream bought will go down. The Law of Demand: the amount bought moves in exactly the opposite direction from the way price moves – if price goes up, the amount bought goes down, if the price goes down, the amount bought increases. Holding constant all other things that might affect the consumer’s behavior, the result is a Demand Curve as in Figure 4. Figure 4 The Demand Curve Changes in the prices of other goods or in real income can increase of reduce demand. Those kinds of shifts in demand are illustrated in Figure 5. For example, assuming that wheat is a superior/normal good, if real income increases the demand will increase, or shift to the right. If real income decreases, the demand will decrease, or shift to the left. 5 Figure 5 Shifts in the Demand Curve The amount of wheat that will be bought at all possible prices is described by the demand curve. The demand curve can be shown with either an equation or a graph. For the wheat market, the demand equation is: Qd = 1000 – 10(Wheat Price) + 3(Corn Price) – 0.5(Butter Price) + .3(Pop) + 0.10(Inc) Where Qd is the amount of wheat bought (measured in millions of bushels), Pop is population and Inc is income. Qd is negatively affected by the price of wheat (the higher the price, the less wheat is bought), it is positively related to the price of corn, negatively related to the price of butter, and positively related to the population and income of consumers (measured in trillions of dollars). If the price of corn is $10 a bushel, the price of butter is $4 per pound, the population is two hundred and fifty million, and consumer income is $5 trillion dollars, then the demand looks like Figure 6. (The price of $50 and the quantity of 603.5 define one point on the demand curve.) Figure 6 The Demand for Wheat 6 Market Equilibrium In this kind of market, the movements in price and amounts bought and sold are explained by the interactions of buyers and sellers in the market. Equilibrium in the market is a combination of price and quantity at which no one (buyer or seller) has any reason to change decisions. This is the point where the demand and supply curves cross (in Figure 7, the equilibrium price is Pe and the equilibrium quantity is Qe). Figure 7 Market Equilibrium A change in demand or supply changes where the equilibrium is, since either way there has been a change in behavior -- either by buyers (demand), or by sellers (supply). Figure 8 shows the results of a rise in demand. For some reason (e.g., a rise in income) the amount demanded at the original equilibrium has increased. At the original equilibrium, the amount people want to buy is larger than the amount firms are willing to sell. Buyers offer higher prices to get what they want, sellers are willing to sell more if they get the higher price. Eventually price reaches a new (higher) equilibrium value (Pe’, Figure 8) and quantity reaches a new (higher) equilibrium value (Qe’, Figure 8). Figure 8 Changes in Market Equilibrium 7 Putting supply and demand together for the wheat market gives the picture below. Equilibrium, given the values of other prices, income, population, input costs, the number of farms, and the weather, is at the intersection of the two lines. Figure 9 Equilibrium in the Wheat Market Market Disturbances This program uses a market -- wheat -- that is as close to perfect competition as can be found in reality. Starting with an initial equilibrium, the program allows you to “disturb” the market in a number of different ways. You can shift demand (up or down) by altering the price of a substitute or a complement, or by changing real income. You can change supply by altering the rainfall, seed cost, or the number of farms. Such changes will cause (at the same price) larger or smaller production (crop) to come to the market. Doing any of these things changes the equilibrium price and quantity. Part of your job is to understand why a particular disturbance caused a move to a particular equilibrium. In the process work out why the total amount spent in each case increases or decreases. (Hint: use the concepts of “price elasticity of demand” and “price elasticity of supply” in figuring this out.) Demand Variables “Demand” means the amounts of a good people in the market are willing and able to buy, depending on the price for this good, prices of other goods, their income, their expectations regarding future prices and income, and the number of people in the market. In this model of the wheat market, the “Demand Variables” are the: consumer’s income, price of butter, and price of corn. You can “disturb the market”, that is, change one of these Demand Variables and observe the results. Changing one of the Demand Variables will “shift” the demand curve and produce a new market equilibrium 8 Supply Variables “Supply” means the amounts of a good people in the market are willing and able to sell depending on the price for this good, costs of production, expectations regarding future prices and revenues, and the number of sellers in the market. In this model of the wheat market, the “Supply Variables” are the: amount of rainfall, seed cost, and the number of farms. You can “disturb the market”, that is change one of these “Supply Variables” and observe the results. Changing one of the “Supply Variables” will “shift” the supply curve and produce a new market equilibrium. Market Regulation After introducing a market disturbance you can interfere with the market’s “natural” behavior. You have two alternatives: 1) you can regulate the price of the product, setting a maximum or a minimum price; or 2) you can order the farmers to produce the amount you tell them to produce, and take whatever price the market gives them for their product. Price Controls When setting a maximum or minimum price check whether you are causing a surplus (excess supply), or a shortage (excess demand). Be sure you know which of these has resulted from your chosen intervention. You should also be concerned with the way price regulation affects buyers and sellers, how it affects the amount spent on the product, and how it affects the amount produced and the amount bought. You should be aware that some of these items depend on the elasticities of demand and/or supply. If you choose to regulate the price, you have certain limitations. The limitations exist to ensure that your intervention actually has an effect. If you set a minimum price, it has to be lower than the price the market would go to by itself (the new equilibrium price). If you were allowed to set a minimum price lower than that, it wouldn’t affect the market and you wouldn’t find out what the effects of interfering with the market are. If you choose to set a maximum price, you are not allowed to set one higher than the market equilibrium. If you did, the price would never get that high and once again, you would not find out what the impact of interference is. (You also cannot set a minimum price so low there is nothing produced, nor a maximum price so high nothing will be bought. You have to leave the market functioning despite your regulation.) Production Controls When you control the amount produced you are coming a bit closer to the way the centrally planned economies function (still partly true for Cuba and the People’s Republic of China). Since they often control price and quantity (and who worked in what industry and more) this isn’t quite the same thing. When you set production it is important to notice whether you are setting it to a value larger or smaller than the one the market would “pick” in equilibrium. This 9 will determine what effect you have on the price of the product. What effect you have on the income of farmers will depend on the price elasticity of demand, so you will need to consider that value. In this part of the program an element of Political Science creeps in. When you intervene in the market you have two groups to consider: farmers and consumers. Depending on what you do you may hurt one group and help the other, or even hurt both groups. Since you are acting as governments do, you need to consider how members of these groups will react politically. Since the United States is a political democracy, the reaction is recorded in the voting record. Your action will either increase or reduce the proportion of voters who support you, and the program reports this. Running the Module When you start running this module the first thing you will see is the “Initial Conditions” screen, showing the original values of the variables that can shift Demand or Supply. At this point you can access the help files (through “Instructions” on the tool bar) or continue. When you continue the next screen shows the original equilibrium—the supply and demand graph and the equilibrium price and quantity if there is no actual disturbance. At this point you can choose to either disturb the market or to regulate it. Assuming you decide to disturb the market, you will see a screen with all the supply and demand variables presented. You need to indicate (by clicking on it) which of these you want to use to disturb the wheat market, then click on Continue. Whichever variable you picked, you will now see its original (default) value and should raise or lower it within the permissible limits. If you choose not to change it you will see the original equilibrium, if you try to exceed the allowed limits on the particular variable you will be scolded and will have to pick a new (legal) value. Once you have successfully disturbed the market you will get to see a new supply and demand graph, indicating the original equilibrium and the new one (with a different colored supply or demand line—depending on which you shifted). You will also see the numerical values of the new equilibrium price and quantity. You then have the choice of continuing to disturb the market in the same way, but with a new value, or starting a new disturbance—in which case you will be back to the screen showing all the supply and demand variables—or you can choose to regulate the market. If you choose to regulate the market you go to a screen in which you must choose to control production (setting output for the industry) or price. If you choose to control production you will be asked to pick and output greater or less than the current equilibrium amount. (The current equilibrium amount will be the original equilibrium if you have not disturbed the market, or if you disturbed it and then went back and restored the original equilibrium. Otherwise the comparison will be with the equilibrium that existed as a result of the market disturbance.) If you decide to control production there are some limits on your power—no negative output, not so much production that the price would wind up negative—paying customers to haul the stuff away. Within those limits you will get the resulting market price and quantity, the incomes of 10 farmers, and the percentage of the vote you would get from farmers and from the rest of the population as a result of your production policy (compared to the votes you’d get without interfering in the market). You might want to consider those voting percentages in the light of changes in farm incomes – which are the amounts that non-farmers spend on wheat. At this point you can reset the amount produced, change the type of regulation, or go disturb the market again. If you choose to change the type of regulation you will go back to the screen for selecting type of regulation again. If you choose Control Price this time, the continue control will lead you to a screen that offers the choice of imposing a price ceiling or a price floor. If you choose to impose a price ceiling, you will (after “Continue”) have to set the price ceiling—a price lower than the current equilibrium price. If you try to set a price ceiling below the equilibrium you will not be allowed to do that. Once you have set a proper price ceiling you will get the results of the regulation, the effects on the price in the illegal market your regulation created, the effect on the amount farmers are willing to produce, on their revenues, and on the profits of criminals. If you don’t like the way criminals profited from your policy, at this point you can choose to hire cops to enforce the price ceiling. If you click on the “Hire Cops” button you will be given the opportunity to decide on a budget for paying the cops. You will not be allowed to spend more on the cops than the total profits currently being made by the criminals, but if you enter a legal amount and click on “Calculate” on the toolbar you will get the results of your entry into law enforcement. At this point you can go back and choose to try the remaining form of regulation (or any other form, or to disturb the market). If you choose to impose a price floor, you will go to a screen that allows you to set a price floor—higher than the current equilibrium price. Once you have entered a valid price you will see the results of your intervention, including the amounts spent by taxpayers to buy up the surplus created by the price floor, and to store it for future use (or until it spoils). Mathematical Model The basic equations of this module are the supply and demand functions. Qs = ( - 1000 + 700(Rain) + 50(Wheat Price)) * (# of Farms/Seed Cost) Qd = 1000 – 10(Wheat Price) + 3(Corn Price) – 0.5(Butter Price) + .3(Pop) + 0.10(Inc) If are looking for the market equilibrium, you want the quantity demanded to be equal to the quantity demanded. Setting Qs equal to Qd and solving the resulting relationship for the price of wheat yields (where Pw is the price of wheat, R is the amount of rain, F is the number of farms, S is the cost of seed, Pc is the price of corn, Pb is the butter price, and I is Inc): Pw = [1000+((1000-700(R)* (F/St))+3(Pc)-0.5(Pb)+0.3(Pop)+0.1(Inc)]/[(50(F/S))+10] 11 If you insert the default values of the various supply and demand variables you should get the original equilibrium price. If you change any of the variables you can get the equilibrium price for the new value of that variable (the effect of disturbing the market). Once you have the equilibrium price, you can substitute the value back into either the supply or demand equation to get the equilibrium quantity. To get the effects of regulating production, take the output you set and put that into the demand curve—the supply curve is irrelevant once you have taken control of production. Solve the demand curve for the price of wheat and insert the values of all the demand variables—you will get the price of wheat that results from your output decision. Since the incomes of farmers are the price of wheat times the quantity (P*Q) you have all the information you need to determine that income. To get the effects of a price floor: insert the ceiling price into the demand equation to get the quantity demanded by people and into the supply equation to get the quantity supplied. The difference between these two values is the amount of the surplus generated by the price floor, and the amount that the government has to buy to keep the price floor intact (avoid having the price go down due to the law of supply and demand). The amount the government spends is the amount of the surplus times the price floor. If the price floor is PF: Government spending=(Qs-Qd)*PF The amount spent on storage is a constant storage cost per unit times the amount of the surplus. To get the effects of a price ceiling: insert the ceiling price into the supply equation. This will tell you the quantity (Qs) that farmers are willing to produce at this price. Once the quantity has been determined the price in the illegal market can be determined. Take the quantity that the farmers were willing to produce at the legal price (which is all the farmers will get) and insert that into the demand equation and solve for the price of wheat. The resulting price is the most that consumers are willing to pay in order to get that amount of wheat. Since the criminals that buy from the farmers and sell to consumers will charge as much for the wheat as they can get, while selling it all, this is the price they will charge consumers. If PI is the illegal price and PC is the ceiling price: PI=[1000 +(3(Pc)) –(0.5(Pb))+(.3(Pop)+(.1(Inc))-Qs]/10 The profit made by criminals is the profit they make on each unit (the price they get from consumers minus what they pay the farmers) times the number of units they sell. Profit = (PI – PC)*Qs Hiring cops reduces the number of units the criminals sell (increases the number of units consumers get at the legal price). If they are still any selling any units, however, their profits per unit will increase. To see how this happens, notice that if the police presence causes some wheat to be sold to consumers at the legal price this does two things. First, it reduces the quantity available for the illegal market. Second, it reduces consumer demand by the same amount. If the 12 amount sold to consumers at the illegal price is QL and the amount sold on the illegal market is QI, then: QI = Qs – QL How much will be sold legally and how much illegally depends on the amount spent on cops relative to the maximum permitted budget. The maximum is set by the amount of profits the criminals made before any cops were hired, and if the proportion of wheat sold legally is named “Percent,” the amount spent on cops is “cops,” and amount of prior criminal profit is “crooks,” the effectiveness is: Percent = [1 – (cops/crooks)2] To get the quantity sold legally, multiply Qs by the value of “Percent.” The price of wheat in the illegal market will be: Pw=1000+ 3(Corn Price) – 0.5(Butter Price) + .3(Pop) + 0.10(Inc)-(.1(Percent)(Qs)) The smaller the quantity sold illegally, the higher the illegal market price and the higher the profit margin (profit per unit) for the criminals. The overall effect on criminal profits depends on the relative amounts of increase in per unit profits and reduction in number of units sold illegally. In the portion of the demand curve where demand is inelastic, the price increase will be large compared to the decline in quantity and profits for criminals will increase. In portions of the demand curve where demand is elastic criminal profits will decline. You should recall that in a straight-line demand curve the price elasticity of demand varies along the curve. 13