Using Area to Find Geometric Probability

... “WALK” when you arrive? To find the probability, draw a segment to represent the number of seconds that each signal is on. ...

... “WALK” when you arrive? To find the probability, draw a segment to represent the number of seconds that each signal is on. ...

Powerpoint

... Probability derived from experiment Toss a drawing pin in the air - two possible outcomes: point up, point down Can we say a priori what the relative probabilities are? (c.f. ‘fair’ coin) If not, then experimentation is a possible source for determining probabilities. (This gets us back to statisti ...

... Probability derived from experiment Toss a drawing pin in the air - two possible outcomes: point up, point down Can we say a priori what the relative probabilities are? (c.f. ‘fair’ coin) If not, then experimentation is a possible source for determining probabilities. (This gets us back to statisti ...

Assessment [feedback page]

... distributions can be confused. They key difference is that the hypergeometric distribution accounts for the fact that previous successes and failures will affect future successes and failures. Drawing a successful item from the population will decrease the number of successful items in the populati ...

... distributions can be confused. They key difference is that the hypergeometric distribution accounts for the fact that previous successes and failures will affect future successes and failures. Drawing a successful item from the population will decrease the number of successful items in the populati ...

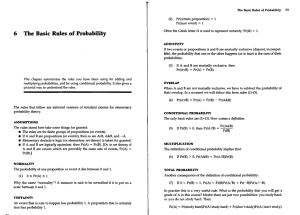

6 The Basic Rules of Probability

... One of Black's students was to go overseas to do some research on Kant. She was afraid that a terrorist would put a bomb on the plane. Black could not convince her that the risk was negligible. So he argued as follows: BLACK: Well, at least you agree that it is almost impossible that two people shou ...

... One of Black's students was to go overseas to do some research on Kant. She was afraid that a terrorist would put a bomb on the plane. Black could not convince her that the risk was negligible. So he argued as follows: BLACK: Well, at least you agree that it is almost impossible that two people shou ...

ACE HW

... 3. Bailey uses the results from an experiment to calculate the probability of each color of block being chosen from a bucket. He says P(red) = 35%, P(blue) = 45%, P(yellow) = 20%. Jarod uses theoretical probability because he knows how many of each color block is in the bucket. He says P(red) = 45%, ...

... 3. Bailey uses the results from an experiment to calculate the probability of each color of block being chosen from a bucket. He says P(red) = 35%, P(blue) = 45%, P(yellow) = 20%. Jarod uses theoretical probability because he knows how many of each color block is in the bucket. He says P(red) = 45%, ...

Probability, Part 2

... carriers for a certain disease. As carriers, they have one normal gene, N, and one gene, D, which codes for the disease. If two parents are both carriers, what is the probability that their first child will have the disease? (The child would need to receive the D gene from each parent to have the di ...

... carriers for a certain disease. As carriers, they have one normal gene, N, and one gene, D, which codes for the disease. If two parents are both carriers, what is the probability that their first child will have the disease? (The child would need to receive the D gene from each parent to have the di ...

PowerPoint - Dr. Justin Bateh

... exactly 3 successes. This is equal to .088. 2. You are asked to find the probability of observing up to 3 successes. In other words, you need to report the probability of observing a number of successes less than or equal to 3. The CUMULATIVE argument to the BINOMDIST function adds all of the prob ...

... exactly 3 successes. This is equal to .088. 2. You are asked to find the probability of observing up to 3 successes. In other words, you need to report the probability of observing a number of successes less than or equal to 3. The CUMULATIVE argument to the BINOMDIST function adds all of the prob ...

Problem of the Day 1. You have 8 nice shirts, 5 pairs of nice pants

... if the numbers used are 1 to 40( no number repeated)? (How many if you can not have adjacent numbers the same?) ...

... if the numbers used are 1 to 40( no number repeated)? (How many if you can not have adjacent numbers the same?) ...

![Assessment [feedback page]](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/014618706_1-be0e375db74b1b2328340284e99b1c99-300x300.png)