The Greedy Triangle Lesson Plan

... “I want to read a fun book about a triangle. As I read, let’s think about what makes him greedy and what shapes you see in the pictures. Then we’ll talk about if you’ve seen these shapes before and what to call each shape.” Procedures (Lesson Content/Skills/Teaching & Learning Strategies): 1. Introd ...

... “I want to read a fun book about a triangle. As I read, let’s think about what makes him greedy and what shapes you see in the pictures. Then we’ll talk about if you’ve seen these shapes before and what to call each shape.” Procedures (Lesson Content/Skills/Teaching & Learning Strategies): 1. Introd ...

Slightly Scalene Mathematics

... Foundation. This paper is for my father, George Barany, who taught me my first mathematical proof—that the angles of a triangle sum to two right angles. I would particularly like to thank Mike Lynch for his generous insights and encouragement. ...

... Foundation. This paper is for my father, George Barany, who taught me my first mathematical proof—that the angles of a triangle sum to two right angles. I would particularly like to thank Mike Lynch for his generous insights and encouragement. ...

A Ch. Y0 Anglar Rotations

... Unfortunately, we don’t have special triangles that have 120 or 150˚ angles. But, if we use our knowledge of similar triangles, we can see an angle of 120˚ corresponds to a triangle of 60˚. We can also see the 150˚ angle would correspond to a 30˚ angle in the similar triangles. Another way of saying ...

... Unfortunately, we don’t have special triangles that have 120 or 150˚ angles. But, if we use our knowledge of similar triangles, we can see an angle of 120˚ corresponds to a triangle of 60˚. We can also see the 150˚ angle would correspond to a 30˚ angle in the similar triangles. Another way of saying ...

8.5b (build)—Constructing Parallel Lines

... finished triangle. Do not change it from now on. Step 3: With the compass point on P, make two arcs, each roughly where the other two vertices of the triangle will be. Step 4: On one of the arcs, mark a point Q that will be a second vertex of the triangle. It does not matter which arc you pick, or w ...

... finished triangle. Do not change it from now on. Step 3: With the compass point on P, make two arcs, each roughly where the other two vertices of the triangle will be. Step 4: On one of the arcs, mark a point Q that will be a second vertex of the triangle. It does not matter which arc you pick, or w ...

the size-change factor

... Similar figures look alike but one is a smaller version of the other. Like Dr. Evil and Mini-Me. It wouldn’t make much sense to make a drawing of this ship the actual size of the ship. ...

... Similar figures look alike but one is a smaller version of the other. Like Dr. Evil and Mini-Me. It wouldn’t make much sense to make a drawing of this ship the actual size of the ship. ...

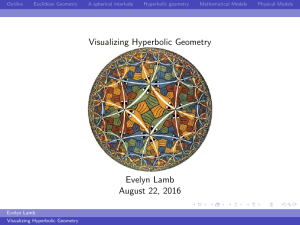

Visualizing Hyperbolic Geometry

... Playfair’s Axiom, hyperbolic style: Between a line L and a point P not on L, there are infinitely many lines through P that do not intersect L. ...

... Playfair’s Axiom, hyperbolic style: Between a line L and a point P not on L, there are infinitely many lines through P that do not intersect L. ...

Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to the Alexandrian Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described in his textbook on geometry: the Elements. Euclid's method consists in assuming a small set of intuitively appealing axioms, and deducing many other propositions (theorems) from these. Although many of Euclid's results had been stated by earlier mathematicians, Euclid was the first to show how these propositions could fit into a comprehensive deductive and logical system. The Elements begins with plane geometry, still taught in secondary school as the first axiomatic system and the first examples of formal proof. It goes on to the solid geometry of three dimensions. Much of the Elements states results of what are now called algebra and number theory, explained in geometrical language.For more than two thousand years, the adjective ""Euclidean"" was unnecessary because no other sort of geometry had been conceived. Euclid's axioms seemed so intuitively obvious (with the possible exception of the parallel postulate) that any theorem proved from them was deemed true in an absolute, often metaphysical, sense. Today, however, many other self-consistent non-Euclidean geometries are known, the first ones having been discovered in the early 19th century. An implication of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity is that physical space itself is not Euclidean, and Euclidean space is a good approximation for it only where the gravitational field is weak.Euclidean geometry is an example of synthetic geometry, in that it proceeds logically from axioms to propositions without the use of coordinates. This is in contrast to analytic geometry, which uses coordinates.