Finite Fields

... • A ring is called a division ring (or skew field) if the non-zero elements form a group under ∗. • A commutative division ring is called a field. Example 2.3 • the integers (Z, +, ∗) form an integral domain but not a field; • the rationals (Q, +, ∗), reals (R, +, ∗) and complex numbers (C, +, ∗) fo ...

... • A ring is called a division ring (or skew field) if the non-zero elements form a group under ∗. • A commutative division ring is called a field. Example 2.3 • the integers (Z, +, ∗) form an integral domain but not a field; • the rationals (Q, +, ∗), reals (R, +, ∗) and complex numbers (C, +, ∗) fo ...

lecture notes as PDF

... • A ring is called a division ring (or skew field) if the non-zero elements form a group under ∗. • A commutative division ring is called a field. Example 2.3 • the integers (Z, +, ∗) form an integral domain but not a field; • the rationals (Q, +, ∗), reals (R, +, ∗) and complex numbers (C, +, ∗) fo ...

... • A ring is called a division ring (or skew field) if the non-zero elements form a group under ∗. • A commutative division ring is called a field. Example 2.3 • the integers (Z, +, ∗) form an integral domain but not a field; • the rationals (Q, +, ∗), reals (R, +, ∗) and complex numbers (C, +, ∗) fo ...

Usha - IIT Guwahati

... using the change of variable xi = x0i + ai to move a to the origin. It is harder to prove that every maximal ideal has the form Ma . Let M be a maximal ideal, and let F denote the field K[x1 , . . . , xn ]/M . We restrict the canonical projection map π : K[x1 , . . . , xn ] → F to the subring K[x1 ...

... using the change of variable xi = x0i + ai to move a to the origin. It is harder to prove that every maximal ideal has the form Ma . Let M be a maximal ideal, and let F denote the field K[x1 , . . . , xn ]/M . We restrict the canonical projection map π : K[x1 , . . . , xn ] → F to the subring K[x1 ...

Introduction for the seminar on complex multiplication

... CM type Φ of K with values in L0 is a set of g embeddings of K into L0 of which no two are complex conjugate to each other (recall that complex conjugation is a well defined automorphism of K). Suppose k has characteristic 0 and A/k has CM by K via ι. Then in some way (we will see the details in ano ...

... CM type Φ of K with values in L0 is a set of g embeddings of K into L0 of which no two are complex conjugate to each other (recall that complex conjugation is a well defined automorphism of K). Suppose k has characteristic 0 and A/k has CM by K via ι. Then in some way (we will see the details in ano ...

On the Prime Ideals in a Commutative Ring

... Proof Let α = |I|. Then we can view α as an ordinal number with the property that each ordinal number less than α has strictly smaller cardinality. (In fact, if we use the formal approach of Kelley, any ordinal number γ may be identified with the set of all ordinal numbers less than γ [11, Theorem 1 ...

... Proof Let α = |I|. Then we can view α as an ordinal number with the property that each ordinal number less than α has strictly smaller cardinality. (In fact, if we use the formal approach of Kelley, any ordinal number γ may be identified with the set of all ordinal numbers less than γ [11, Theorem 1 ...

REMARKS ON WILMSHURST`S THEOREM 1. Introduction Suppose

... Remark 1. If F is coercive, its topological degree coincides with the degree of its extension to the one point compactification S d = R ∪ {∞}. In this case let y ∈ Rd be a regular value P for F (Sard’s lemma implies the generic y is a regular value); then deg F = x∈F −1 (y) sign(JFx ) (coercivity im ...

... Remark 1. If F is coercive, its topological degree coincides with the degree of its extension to the one point compactification S d = R ∪ {∞}. In this case let y ∈ Rd be a regular value P for F (Sard’s lemma implies the generic y is a regular value); then deg F = x∈F −1 (y) sign(JFx ) (coercivity im ...

Introduction to Algebraic Number Theory

... (e) Deeper proof of Gauss’s quadratic reciprocity law in terms of arithmetic of cyclotomic fields Q(e2πi/n ), which leads to class field theory. 4. Wiles’s proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem, i.e., xn +y n = z n has no nontrivial integer solutions, uses methods from algebraic number theory extensively ( ...

... (e) Deeper proof of Gauss’s quadratic reciprocity law in terms of arithmetic of cyclotomic fields Q(e2πi/n ), which leads to class field theory. 4. Wiles’s proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem, i.e., xn +y n = z n has no nontrivial integer solutions, uses methods from algebraic number theory extensively ( ...

Math 210B. Absolute Galois groups and fundamental groups 1

... fundamental groups. It also turns out that Galois cohomology, to be discussed later in the course, exhibits many features of topological cohomology, though the full force of the analogy can only be seen when fields are replaced with higher-dimensional algebro-geometric objects. (The most satisfactor ...

... fundamental groups. It also turns out that Galois cohomology, to be discussed later in the course, exhibits many features of topological cohomology, though the full force of the analogy can only be seen when fields are replaced with higher-dimensional algebro-geometric objects. (The most satisfactor ...

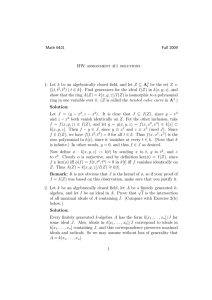

Solutions

... Suppose first that x is integral over A, and let B be a valuation ring of K containing A. Then either x ∈ B or x−1 ∈ B. If x ∈ B, we are done. If x−1 ∈ B, then by the integrality of x we have xn + a1 xn−1 + · · · + an−1 x + an = 0 with ai ∈ A, and thus x = −(a1 + a2 x−1 + · · · + an (x−1 )n−1 ) ∈ B ...

... Suppose first that x is integral over A, and let B be a valuation ring of K containing A. Then either x ∈ B or x−1 ∈ B. If x ∈ B, we are done. If x−1 ∈ B, then by the integrality of x we have xn + a1 xn−1 + · · · + an−1 x + an = 0 with ai ∈ A, and thus x = −(a1 + a2 x−1 + · · · + an (x−1 )n−1 ) ∈ B ...