* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Masters and Gautama: A Synthesis of Buddhist Philosophy

Relics associated with Buddha wikipedia , lookup

Wat Phra Kaew wikipedia , lookup

Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent wikipedia , lookup

Silk Road transmission of Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist cosmology of the Theravada school wikipedia , lookup

Early Buddhist schools wikipedia , lookup

Buddha-nature wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist ethics wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and psychology wikipedia , lookup

History of Buddhism in India wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and sexual orientation wikipedia , lookup

Greco-Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

History of Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Sanghyang Adi Buddha wikipedia , lookup

Triratna Buddhist Community wikipedia , lookup

Dhyāna in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Pre-sectarian Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist philosophy wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism in Myanmar wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Western philosophy wikipedia , lookup

Gautama Buddha wikipedia , lookup

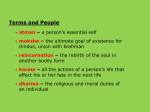

David Chana Dr. Noah Hilgert English 105 13 October 2003 Masters and Gautama: A Synthesis of Buddhist Philosophy Regardless of who we are or where we come from, we are unlucky enough to be subject to a world consisting of modifiers, pre-established social elements, systems of opinion and belief, which, though we may be unaware of them while they work their magic on us, ultimately serve to wrap us in a prison of thought. At the same time, there exist modifiers which may serve to free us. Depending on the right conditions, the time, we can be fortunate enough to see through the shroud pulled over our head at birth, to the true explanation of why we’re here, the truth of our existence. It’s for this reason that I’ve chosen to bring together two articles which, in their own way, relate the story of just such an occurrence- where a person comes to the realization that the world is absolutely different than what their influences in life have led them to think of it as. The first is an excerpt from a book, which acquaints us with the history of the Buddha, his exposure and realization of the vagaries of life, and his subsequent pursuit of enlightenment thereafter. The second is the story of a man on death row in San Quentin prison who, very comparatively, through the study of meditation and spiritualism, raises his perception of life to a new level and begins to see through his own veil of thought, recognizing the horrible falsehood of his past. These two texts clearly illustrate the potential every person has to change themselves, their lives, by simply turning around and evaluating the way they see and interpret the world. Together they demonstrate how anyone can rise over the problems of their past, reject what they’ve grown accustomed to thinking of as normal, in an effort to better themselves. From the book “The World’s Religions,” the excerpt “Buddhism” by Huston Smith gives us an informative, yet summarized look, into the life of a man named Siddhartha Gautama. Born of a king into a life of luxury, in what is now Nepal around 563 B.C., Gautama was prophesized to be the “world redeemer”(par. 9), the one who would see the truth of existence and eventually lead people from Brahmanism and the vagaries of life. This story has been told by many authors countless times, there is no real unique quality in Huston’s telling, but this version of the narrative, with it’s clarity and straightforwardness, makes it a perfect selection to use for the telling of the Buddha’s past. For his first 29 years Gautama, whose father provided him with endless luxury in fear he would become what he was prophesized to be, lived a fairytale life. Described as being wealthy and physically attractive, the noble child was immersed in surroundings of continuous beauty and health. The sick or the old were allowed nowhere near him. Eventually the prince married a woman who gave him a family, and so it seemed he was destined to be the throne’s heir. Paradoxically, Gautama was at some point in his twenties exposed to what are called The Four Passing Sights; despite his father’s greatest efforts, the young prince, while being driven in a horse carriage through the countryside, came across four examples of human suffering in their most obvious form. These sites revealed to Gautama a far deeper understanding of existence than what he’d grown accustomed to, and the result proved to be irreversible. The first was an aging man, something the prince had never seen. From this he reaped his first understanding of old age. The second was a person ridden with disease, and the third, a dead body. From these came the realization that the pleasures of life to which he’d grown so accustomed were definitely with end, impermanent, and so Gautama made the decision to change his life completely. "Life,” Gautama said to himself, “is subject to age and death. Where is the realm of life in which there is neither age nor death?"(par. 11) This revelation, this understanding of the inevitability of “bodily pain and passage,”(par. 12) erased the charms of worldly pleasure from Gautama’s senses. He brooded, contemplated the futility in the endless chase of contentment and satisfaction and eventually, in what is called his Great Going Forth, made the decision to break away from it all. The fourth passing sight was a monk, delivering to the prince the clear and obvious alternative, the solution, of withdrawing from the world. With this suggestion in mind, Gautama, in his 29th year, fled the palace in an effort to seek the truth, to find the source of satisfaction, enlightenment. Gautama’s time as a traveler was spent in three phases within six years. He began as a hermit in the forest, then went on to seek the wisdom of the day’s greatest Hindu masters from whom he learned raja yoga and Hindu philosophy. His time of learning ended in the company of a group of ascetics. From these experiences he learned the futility of living in extremes, and devised his own theory on living a life of equality, of rationality, in which the body is given what it needs to function optimally and nothing more. Finally, Gautama’s quest ended somewhere in northeastern India where, utilizing a form of thought concentration based on his knowledge of raja yoga, he sat and vowed to achieve what he had set out to do. The story tells of distractions coming to him desire, physical pain, and reason – in the form of Mara, a kind of God-like figure set out to disrupt his concentration and see him fail. Upon overcoming these distractions, absorbed in meditation, Gautama achieved enlightenment and “the gods of heaven descended in rapture to ten the victor with garlands and perfumes.”(par. 17) So, as it is, the story of Buddhism begins with a man who “awakes”, a man who roused himself from the slumber of typical human consciousness. When asked what he was by those he taught, the answer given became his title. “Are you a god? they asked. No. An angel? No. A saint? No. Then what are you? Buddha answered, I am awake.”(par. 2) In Sanskrit, the root budh means both to know and to wake up. Buddha, then, translates to the "Enlightened One," or the "Awakened One."(par. 3) In “Tylenol Prayer Beads,” a short story from the book “Searching for Your Soul: Writers of Many Faiths Share Their Personal Stories of Spiritual Discovery,” the author Jarvis Jay Masters, a man accused of murder, tells his story of dealing with the challenges of court and prison through meditation and a study of spiritualism. Faced with death, Masters turns to coping with his situation over living in a world of endless fear and anxiety. With his narrative skill, Jarvis makes an indirect appeal to the reader, asking if a person who discovers himself, a person whose experience leads them to a level of consciousness high enough to contemplate the karma of their past actions, deserves to be punished for the ignorance of that past. The story begins with Masters’ telling of his murder trial. A private investigator working on his case brought him books on the Buddha’s teachings, and to stay calm during the trial he began sitting in meditation ahead of time. His early morning prison hours were spent absorbed in the practice in an effort to calm himself before the day’s court deliberations. Jarvis reveals that in time his ability to better cope with what was happening around him increased- the questions related to his mother, the picking apart and analyzing of his past. “Through meditation,” relates Jarvis, “I learned to slow down and take a few deep breaths, to take everything in, not to run from the pain, but to sit with it, confront it, give it the companion it had never had.” (par. 3) Masters quickly builds to the point where he contacts a student of a Tibetan Lama named Rinpoche, with whom he quickly develops a kind of supportive relationship. With time he meets the student, who eventually brings Rinpoche to San Quentin to meet with him. He describes his deep appreciation for Rinpoche, how he was someone with a stoic yet loveable character who helped guide him to an even deeper understanding of Buddhism. “Here's a guy,” says Jarvis, “who can take me out of prison even as I remain here. He won't dress me in Buddhist garb, but accept me as I am."(par. 9) Inspired by his lessons from and observations of Rinpoche, Masters describes in detail his desire one evening to create a mala, a string of prayer beads, with a sharpened staple, thread from his jeans, and a bottle of Tylenol. At the end of this segment, he goes into meditation using his improvised mala. The story then makes a leap to the future, to a point where Masters experiences what can be described as a kind of epiphany, where he relates a moment in which he is seeing the world from a revised perspective, through a new lens of thought, from the point-of-view of person who wants to be a Buddhist but is oppressed by the system in which he’s entrapped. He describes in detail an event one day on the prison grounds, where two men fall into a fight and one kills the other. In this conclusionary telling, Masters makes his most direct appeal to a readers’ sympathy for him, saying “Why am I lying here like this?” at a point when the rifle guards have ordered everyone to lay face down on the ground, “Is this all real? Shit! How long can I go on trying to be a Buddhist in this prison culture that has me lying face down? Who am I kidding?” He then reaches a conclusion within himself in regards to life - “I realized that what really matters isn't where we are or what's going on around us, but what's in our hearts while its happening.” Masters ends his story with describing his choice to become a teacher of love and compassion in San Quentin prison. Though dangerous to do so, he admits, Masters is compelled by what can be seen as the end result of a kind of enlightenment, a seeing into the truth of life. Masters and Gautama share solid common ground in the sense that they both discover, through revelationary periods, a prison of thought inside of which they are both inmates. Between “Buddhism” by Huston Smith and “Tylenol Prayer Beads” by Jarvis Masters, we see how the stories of two men, though separated by two continents and over 2500 years, are paralleled in this sense. Huston, an acclaimed writer who has incorporated the world’s religions into his many works, and Masters, a prisoner with the experience of being an inmate on death row, cover a common theme in both their works – Buddhist philosophy. The most immediate comparison that can be drawn between Gautama and Masters is their devotion to spiritualism and meditation, driven by events that caused them to see the world in a different light. “I became committed to my meditation practice,”(par. 3) stated Masters in a way that almost mirrors the Buddha’s adamant pursuit of enlightenment. The Four Sights that caused the Buddha to eventually flee his palace can be seen in Masters’ exposure to prison, his ordeal of having to cope with eminent death, and the prison fight scene. Another similarity in the lives of these two characters, almost uncanny in it’s coincidence, is the common bond they shared through their interaction with a religious intermediate- a monk. Gautama sought out the advice and wisdom of the Hindu masters of his time, and 2500 years later Rinpoche became the equivalent of these men in service to Masters. From these teachings, the two take on similar quests, coincidentally unaware of what their true goal is at the start, and end up finding freedom from the mental torment that drove them to begin. The most obvious reference between the two works exists where both Gautama and Masters choose to pursue a life of teaching, motivated by the desire to good for others. As Masters states, “…I see now that we become better people if we can touch a hardened soul, bring joy into someone's life, or just be an example for others, instead of hiding behind our silence.”(par. 23) This is interestingly comparable to what the Buddha says in response to Mara when questioned what he can possibly do with what he has learned: “…how show what can only be found, teach what can only be learned?” asked Mara, “Why bother to play the idiot before an uncomprehending audience? Why not wash one's hands of the whole hot world — be done with the body and slip at once into Nirvana?” To which the Buddha replied, "There will be some who will understand,”(par. 19) and the Buddha devoted himself to the teaching of his discovery. From these two articles, we can see not only the value of looking inside oneself for answers to life, but the positive effects of the embracing of Buddhist philosophical values becomes apparent as well. Is it not obvious that we live life in a fashion out of step with what clear, unfocused thought can give us, with logic? Is it not made obvious by these two articles the dependency we have on falsely-based, pre-fed systems of thought, and the subsequent release that comes from rejecting these systems? In as much as Gautama chose to turn away from the life to which he’d grown accustomed, Masters took the step towards embracing his past in an effort to understand himself and teach others. The result of both stories is obvious: for Gautama, enlightenment. For Masters, a release from the torture of his past and his present conditions, the affects of which can be compared to enlightenment. Perhaps from these stories we can see the futility in embracing the past and the systems of thought we have been pulled into, captured by. Perhaps through the overcoming of these “prisons” we can hope to experience rewards similar to those Masters and Gautama became familiar with. Smith, Huston. “Buddhism.” The World’s Religions. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991. Masters, Jarvis Jay. “Tylenol Prayer Beads.” Searching for Your Soul: Writers of Many Faiths Share Their Personal Stories of Spiritual Discovery. Ed. Katherine Kurs. Junction City: Padma, 1997.