* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download THE BROTHERS KARAMAZOV The Brothers Karamazov

Survey

Document related concepts

Catholic views on God wikipedia , lookup

Aristotelian ethics wikipedia , lookup

Alasdair MacIntyre wikipedia , lookup

Ethical intuitionism wikipedia , lookup

Arthur Schafer wikipedia , lookup

Fear and Trembling wikipedia , lookup

Thomas Hill Green wikipedia , lookup

Ethics of artificial intelligence wikipedia , lookup

Clare Palmer wikipedia , lookup

Immanuel Kant wikipedia , lookup

Business ethics wikipedia , lookup

Jewish ethics wikipedia , lookup

Morality and religion wikipedia , lookup

Ethics in religion wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

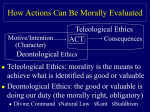

1 DOSTOEVSKY’S CALL FOR ETHICS IN THE BROTHERS KARAMAZOV Dostoevsky’s classic The Brothers Karamazov is often viewed as a defense of traditional religious belief against the skepticism of modernism. The classic tale first appears to demonstrate the superiority of religious ethics as demonstrated by the story’s protagonist. An examination of Dostoevsky’s work reveals an ethical perspective that clearly reflects Kantian influences. Though convinced of God’s existence, Kant was committed to formalizing an ethical system that was based on logic and duty that did not require belief in the supernatural. This paper explores the ethical themes of The Brothers Karamazov and Dostoevsky’s call for duty- based ethics. A Traditional Interpretation The classic interpretation of Dostoevsky’s treatment of religion in The Brothers Karamazov can be summarized as the triumph of faith of intellectual skepticism. The story unfolds how three brothers approach the challenges of life and doubt from three starkly different perspectives. Alyosha is undoubtedly the hero of the story. The youngest brother is described as having a “simple faith” whose defining quality is a genuine love of humanity. Alyosha is contrasted by his skeptical oldest brother. Ivan is viewed as the rational intellectual who struggles with the concept of God. Like many others, Ivan finds it impossible to reconcile how an all-powerful, all-knowing, and supposedly all-loving God can allow for the existence of evil in the world. Ivan’s arguments encourage disaster as the story unfolds. His persistent doubt and skeptical views of God and morality lead to the murder of his father and eventually his own madness. Ivan’s classic quote “Without God, everything is permitted”, is traditionally seen as Dostoevsky’s conclusion that true morality must be based on faith in God. When presented with 2 Ivan’s thoughts, the middle brother appears to come to the same conclusion. In chapter seventythree, Mitya states “But what will become of men then? I asked him, ‘without God an immortal life? All things are lawful then, they can do what they like?’” The reader may be left with the conclusion that indeed faith is superior to skepticism from a pragmatic perspective. So widespread is this common view that many are tempted to dismiss Dostoevsky as yet another religious philosopher who accepts the need for blind faith much in the same way Soren Kierkegaard argues for his “leap of faith” in his existentialist perspective. In responding to this common interpretation held by Arther Trace and others, Barineau states “Dostoevsky, according to Trace, ultimately concludes that religion, and religion alone, can save humanity from itself “.1 Dostoevsky does indeed champion religion, but not in the common interpretation. What Dostoevsky argues is far more complex and ingenious. Instead of blind faith, the argument is made that faith should be derived from ethics and only then can it address the gnawing questions of skepticism. To achieve this, it is argued that Dostoevsky drew upon the philosophical work of Immanuel Kant. The Kantian Connection The question arises: did Dostoevsky know Kant? Though the answer is not apparent, there are several clues to a Kantian influence on Dostoevsky’s philosophy and theology. The first clue lies in the person of Nikolay Karamzin. Karazim was a famous Russian historian and writer of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His work was very well known to Dostoevsky and other educated Russians of the period. It is known that Karamzin visited Immanuel Kant a year after Kant’s famous Critique of Practical Reason was published. It is possible that Dostoevsky 3 was familiar with the philosophy of Kant even though this clue is highly circumstantial. The stronger evidence comes from an analysis of the arguments used by both Dostoevsky and Kant. There are striking similarities between Kant and Dostoevsky regarding their views of immortality. James Scanlan observed that in his reflections on his wife’s death published in 1864, Dostoevsky states: But in my judgment, to attain such a great goal [moral perfection] is completely meaningless if, once it is attained, everything is extinguished and disappears—that is, if a person has no life though the goal has been attained. Consequently, there is a future life in paradise.2 This logic is very similar to Kant’s argument for the enduring self. In his Critique of Practical Reason, Kant argues that we are presented with a categorical moral imperative to treat others as ends in themselves, never as a means. He further argues that perfect accordance of the human will with that imperative is impossible in this life. Thus, there must be a future in which the quest for perfection continues. There can be no moral obligation to do the impossible. Kant’s logic is simple and yet profound. He argues that we are obligated to be morally perfect but this is impossible to achieve in this world so there must be another. The reality that morality is an imperative is proof of an afterlife since there can be no demands to do the impossible. Kant and Dostoevsky share an uncanny similarity in their arguments for immortality. Both arguments represent a reductio ad absurdum. This form of argument establishes a proposition by showing the denial of the proposition leads to absurdity. Kant argues that without immortality, the person would not have an infinite time to pursue moral perfection which is required. For Dostoevsky, without immortality, the person commanded to achieve moral 4 perfection would be only rewarded with extinction for achieving it. In both cases, it is shown to be absurd to believe that human life ends on earth. The similarity between the two thinkers regarding theology is also apparent in how they understand ethics. From Theology to Ethics Dostoevsky employs logic and reasoning to support his belief in immortality much in the same way Kant does. He challenges the idea that reason can “prove” the existence of God and the enduring self but does not treat reason as having no role in the discussion as the irrationalists do (Soren Kierkegaard). For Dostoevsky, the rational belief in immortality is connected to ethics and ethics is based on the duty to love people. Consider the famous statement from The Brothers Karamazov “there is no virtue if there is not immortality” 3. Like his argument for immortality, this is a reductio ad absurdum. The key point here is that Dostoevsky is not arguing that we need religion for ethics, but that the existence of ethics proves there is immortality. The plot of the story affirms this. Ivan Karamazov eventually realizes that there is virtue even in the presence of doubt about immortality. This affirms the reductio and with the existence of immortality comes the existence of God. Dostoevsky also uses the protagonists of the story to demonstrate the relationship he sees between religion and ethics. As the hero of the story, Alyosha represents someone who is religious because he loves people rather than someone who loves people because he is religious. As Dostoevsky states, First, I want to make it clear that young Alyosha was in no sense a fanatic. In my opinion at least, he was not even a mystic. Let me tell you my opinion of him right from the start: he was just a boy who very early in life had come to love his fellow man and if he chose to enter a monastery, it was simply because at one point that course had caught his 5 imagination and he had become convinced that it was the ideal way to escape from the darkness of the wicked world, a way that would lead him toward light and love.4 Dostoevsky intentionally distances the hero of the story from fanaticism. In fact, religion is only seen as a channel for loving people which is Alyosha’s distinguishing characteristic. It is this virtue of love that appears to be at the center of Dostoevsky’s ethical system and not religion. A second example of this is found in the character of Father Zosima. Zosima is a respected elder who is a mentor to Alyosha. His wisdom is seen at the start of the book when he counsels a woman who is struggling with her faith. Zosima encourages the woman to “try and love your neighbors, love them actively and unceasingly. And as you learn to love them more and more, you will be more and more convinced of the existence of God and of the immortality of your soul”.5 To Father Zosima, the ethics of loving others leads to genuine faith. It is noteworthy that it is not faith and religion that lead to ethics. Granted, Christ commanded people to love each other and in this it is a religious ethic. But the parallels to Kantian philosophy indicate that Dostoevsky is arguing for a faith derived from ethics. In his Critique of Practical Reason, Kant argues that man has a moral obligation to seek the highest good, and that good is virtuousness and happiness. Virtuousness, according to Kant, consists of fulfilling one’s duty and happiness is the reward for that virtuousness. He states “Thus the highest good is practically possibly only on the supposition of the immortality of the soul, and the latter, as inseparably bound to the moral law, is a postulate of pure practical reason.”6 Kant’s Categorical Imperative consists of two main points. First, something can only be considered ethical if it can be universally applied. In other words, there are no exceptions. Second, never treat people as a means to an end. There should be no exploitation of people since 6 people are moral agents. From this perspective the duty that can be universally applied and avoids exploitation is genuine love for all people. This is the argument that Kant makes and it is also the argument Dostoevsky makes. Maurice Barineau points out that Dostoevsky is not saying that religion trumps doubt as commonly understood. But rather, religion comes from ethics and not the other way around. He astutely states that Attempts to derive theology from ethical theory are rare; and, as far as I can determine, Kant was the first to make such an attempt. The rarity of such an endeavor and Dostoevsky’s familiarity with Kant’s ideas suggest more than mere coincidence.7 Indeed it is not a coincidence. The arguments from both Kantian philosophy, the plot of the story, and the words of key characters indicate that Dostoevsky is arguing for an ethics that is based not on blind faith and obedience to religious dogma but based on love for humanity. Such love proves the existence of God and dictates rational faith. Conclusion Few novels have had the impact on theology and philosophy as The Brothers Karamazov. Dostoevsky tackles deep philosophical and theological issues by championing an ethics based on the rational duty of love for humanity. This is Kantian at its core and not simply a refutation of skepticism in favor of blind faith. Alyosha is the hero of the story not because of religious fervor but because he was true to his duty as a human to love others. The novel takes great lengths to show how both the religious and unreligious can be ethical and unethical. Dostoevsky calls the reader to a life of ethics that is free of intellectual ambiguity and apathy but supported by logic and reasoning. He is not advocating blind faith as the ideal path of life but argues effectively that the understanding of a good life is the key to understanding immortality and God. 7 1 Maurice Barineau. “The triumph of ethics over doubt: Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. Retrieved from http://www.funnygolfbooks.com/the-triumph-of-ethics-over-doubt-dostoevskys-the-brothers-karamazov/ 2 James Scanlan. “Dostoevsky’s arguments for immortality. Russian Review, 59, no. 1 (200): 1. 3 Fyodor Dostoevsky. The Brothers Karamazov. Translated by Andrew H. MacAndrew. Introductory Essay by Konstantin Mochulsky. New York: Bantam Books, (1981): 80. 4 Ibid, 20. 5 Ibid. 64 6 Immanuel Kant. Critique of Practical Reason. Translated with Introduction by Lewis White Beck. Indianapolis: Bos-Merrill Educational Publishing (1956): 127. 7 Maurice Barineau. “The triumph of ethics over doubt: Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. Retrieved from http://www.funnygolfbooks.com/the-triumph-of-ethics-over-doubt-dostoevskys-the-brothers-karamazov/ Bibliography Barineau, R. (1993). The triumph of ethics over doubt: Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. Retrieved from http://www.funnygolfbooks.com/the-triumph-of-ethics-over-doubtdostoevskys-the-brothers-karamazov/ Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov. Translated by Andrew H. MacAndrew. Introductory Essay by Konstantin Mochulsky. New York: Bantam Books, 1981. Frank, J. Dostoevsky: The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1976. Kant, I. Critique of Practical Reason. Translated with Introduction by Lewis White Beck. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Educational Publishing, 1956. Scanlan, J. P. (2000). Dostoevsky's Arguments for Immortality. Russian Review, 59(1), 1 Images Book Image: http://thecreativeactionnetwork.com/shop/&tag=the-brothers-karamazov&s=0 8 Dostoevsky: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dostoevsky_1872.jpg Kant Doll: http://upstartcrowtrading.com/online-store/magnetic-personalities