* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES MONETARY POLICY MATTER? A NEW TEST IN

Survey

Document related concepts

Nouriel Roubini wikipedia , lookup

Modern Monetary Theory wikipedia , lookup

Fear of floating wikipedia , lookup

Milton Friedman wikipedia , lookup

Non-monetary economy wikipedia , lookup

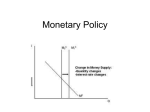

Interest rate wikipedia , lookup

Fiscal multiplier wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative easing wikipedia , lookup

Inflation targeting wikipedia , lookup

Long Depression wikipedia , lookup

Helicopter money wikipedia , lookup

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Early 1980s recession wikipedia , lookup

Money supply wikipedia , lookup

Transcript