* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Kutiyattam And Asian Theatre Traditions

Survey

Document related concepts

Augustan drama wikipedia , lookup

Improvisational theatre wikipedia , lookup

Development of musical theatre wikipedia , lookup

Antitheatricality wikipedia , lookup

Theatre of the Absurd wikipedia , lookup

Theatre of the Oppressed wikipedia , lookup

History of theatre wikipedia , lookup

Meta-reference wikipedia , lookup

Theatre of France wikipedia , lookup

Theater (structure) wikipedia , lookup

English Renaissance theatre wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

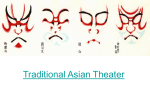

KEYNOTE ADDRESS KUTIYATTAM AND ASIAN THEATRE TRADITIONS By Farley Richmond, Professor University of Georgia Athens, GA Namaskaram It is an enormous pleasure for me to address this gathering. I am honored to be here among so many familiar faces, friends and colleagues, teachers and students. I feel as though I have come home. I want to especially thank Dr. Diane Daugherty, a colleague and longtime friend, and all the members of the organizing committee for inviting me to participate in this conference on “Kutiyattam and Asian Theatre.” It goes without saying that without the efforts of all those responsible, as well as the good offices of UNESCO, today would not have been possible. Kutiyattam has long deserved the world’s attention. UNESCO has bestowed on it the recognition it justly deserves. There are many other individuals and groups that have led us to this day. Unfortunately, many of them are no longer with us. This day belong to them and to the artists assembled here, as well as to devoted supporters and critics like yourselves, who have weathered the many year of struggle that are now part of the history of this wonderful and unique genre of performance. I am glad to have played a small role in that struggle. Kutiyattam and Asian Theatre is a very big topic indeed. Where should I begin? During nearly forty years of teaching I have devoted a great many classes to exploring various aspects of Asian theatre. American undergraduates, and even post-graduate students, know so little about Asia or Asian theatre that most of my time has been spent surveying the subject as a whole rather than taking an in-depth look at any one subject. Needless to say, even a class devoted strictly to a thorough examination of Indian theatre is virtually impossible owing to the complexity of the topic. When Phil Zarrilli, Lee Swann and I published Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance over a decade ago we felt humbled by the enormity of the task and chose to confine ourselves to what we each felt we knew best, realizing that we could never hope to cover the whole field in detail. Asian theatre and drama exists over a huge and diverse geographical region of the globe bridging several continents, including tens of thousands of islands, vast rivers and several oceans and seas, the highest mountain range in the world and some of the most desolate spots on earth, places with the heaviest rain fall, and the driest places on earth. Asian theatre and drama exists in more languages and dialects than I care to count. Many of these languages are very ancient, some are even archaic, and a few are ultra-modern. -1- Some owe their survival to symbolic gesture and movement alone and not to the spoken or chanted word. Asian theatre thrives in the most populous countries in the world and in some of the smallest kingdoms and principalities with minuscule populations. It boasts many extremes: genres of puppetry that appeal to thousands and those that are performed only to please gods and the spirit world; it may be glorified by exquisitely carved masks thought to be endowed with special powers to transform and possess their wearer or simply the unadorned faces of the performers; costumes of expensive material, intricately woven and constructed, or everyday street dress; it may be accompanied by large orchestras with many exotic or unique instruments or devoid of music altogether; it may be entirely danced or shorn of any dance whatsoever; some genres are elaborately staged in specially designed theatres others are performed on street corners or in factory yards; many of the older genres are lengthy affairs, extending over several days or weeks, others require only a few hours of playing time; many are very ancient in origin and some are newly minted. In his Introduction to the Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre, published over ten years ago, Jim Brandon speculated that at the time of writing there might well be as many as 700 to 800 distinct genres of performance in the region. Just think of it, 700 to 800 separate, identifiable genres! He went on to speculate that “no one knows the full extent of the performing arts….there are too many remote regions, and there is too much daily change for anyone to know for certain.” Who can disagree with him even today? We do know that kutiyattam may be counted among the performing arts of the region and that it occupies an important and unique place, not only in India but also in the whole of Asia and now the world. What is it about kutiyattam that is unique, setting it apart from all other genres of performance? I am sure that this gathering of experts will focus on this as well as many other issues. My students are fond of using the Internet to search for sources of information. Indeed, it has become a measure of the success of their initial research to find data on some topic or another on the Internet. And so I went to that popular search engine Google to compare the “hits” for kutiyattam as a means of linking me to information that is out there for millions and millions of people around the world to search and link to. In doing this I thought to compare the number of hits for kutiyattam with those of some of the more familiar genres of performance for which Asia may be justly proud. Let me share that result with you. I came up with a little more than three and a half million hits for Beijing Opera alone, arguably China’s most significant genre of performance. Noh and Kabuki of Japan boast nearly two million hits each. -2- By comparison kathakali, perhaps India’s best-known genre of performance in the west, boasts only two hundred and fifty-four thousand hits. Now compare this number with the mere thirteen thousand three hundred hits for kutiyattam. Needless to say, we can’t measure or compare the quality of the hits that link anyone in the world with Internet access to information on kutiyattam. But I hope you begin to realize how the Internet may tell us something basic about just how much more work has yet to be done to bring kutiyattam to the attention of students and scholars throughout the modern world. Without belaboring the point, I remember searching Google for kutiyattam a few years before the UNESCO designation and coming up with a mere 400 or so hits. So progress has and is being made in this arena. And I suspect and hope that in the next few years there will be an explosion in the number of hits for kutiyattam. That might serve as a sign that information on it is available and being sought by more people. At the same time that UNESCO was recognizing kutiyattam, it was also citing the Noh of Japan. For a moment I want to compare the similarities and difference between these two great arts. I do so because I have always found them to possess many of the same basic features. And I believe a thorough study comparing both would be a profitable exercise. Those of you who are familiar with Noh will please excuse me for overlooking any obvious facts. Both Noh and kutiyattam are historically significant to the cultures from which they spring. They are even considered “classical arts,” in today’s parlance. Both are slow in pace and refined in expression. That is, they linger over details that allow audiences to savor the feelings that are generated by the characters. Both arts are difficult to master. Noh and kutiyattam use an array of symbolic physical and vocal expression to convey meaning. The stage movements of characters, for example, do not replicate those of people in everyday life. A circling movement in Noh may signify traveling a great distance. In kutiyattam it may suggest going from one locale to another. In both forms there is a conventional placement of characters on stage in relation to each other according to rank. In Noh this depends on the type of role being portrayed. For example the waki or “sideman” who questions the shite, the central character or “doer,” has a special location on the stage that is appropriate to his rank in the hierarchy. A special pillar is even named after him because he sits at its base when he is not speaking. When a Noh character enters he usually announces who he is, where he is going, and the dramatic circumstances surrounding his journey. (Incidentally, characters in Beijing Opera do virtually the same thing when they first enter the stage.) In some ways this is similar to the introduction of each of the characters in a kutiyattam performance. Costumes and makeup in each tend to identify the rank and importance of a character. Great respect is shown in both arts to the training process. Elders are venerated and training begins at a very young age in order that a student may have ample opportunity to -3- master the art. Like so many genres of traditional performance, beginning training at an early age allows the master to shape and mold both mind and body of the trainee to the rigors of the art, to formulate respect for elders and the accomplishments of the past. Learning more challenging and suitable roles often depends on continued, hard, and progressively more difficult training. Indeed, artists in both genres usually consider training to be a lifetime commitment. The stages on which both arts were designed to be seen are square, roofed structures. (Paranthetically, the teahouse theatres of ancient China were also square roofed structures.) These roofed stages are now located inside larger buildings. In the case of the Noh this transition seems to have begun with roofed stage structures located inside the courtyards of Zen shrines. The journey of the square roofed kutiyattam stage to its location inside the kuttumpalam appears to have been prescribed by rules laid down in the Natyasastra. The Noh stages are constructed entirely of polished cypress wood and have a bridge linking the stage to the dressing room. By contrast, as you know, the base of the kutiyattam stages are ordinarily constructed of stone with wooden pillars, roof and a back wall with two doors that link the stage to the dressing room. Entrances and exits on these stages have symbolic meaning and significance and there are clear-cut procedures for using entrances and exits. The actor is the focus of attention in both genres. Musicians occupy a space directly behind the performers in both. Although there is a stylized painting of a gnarled pine tree as a background behind the Noh actors, the pine is not meant to be a scenic representation but is used to symbolize longevity. There is no scenery whatsoever behind kutiyattam actors. Both arts are associated with religion and ritual. Zen Buddhism served as the basis for Noh and Hinduism for the development of kutiyattam. Both arts are governed by strict rules of execution. The rasa/bhava theory found in the Natyasastra plays a major role in governing execution of emotional expression in performances of kutiyattam. The yugen theory referred to in the works of Zeami guides aesthetic considerations in Noh. Noh has served as a source for the development of kabuki, considered the more popular genre of performance, appealing to a different class of individuals altogether. Kutiyattam helped lead to the development of kathakali which, like kabuki, appeals to the general public. Both Noh and kutiyattam were designed to address a small number of spectators. They were not designed to be popular among the masses. -4- There are many differences between Noh and kutiyattam, some of them notable. To my mind the following are only a few of the more fundamental differences. Male actors portray all the roles in the professional performances of Noh. Even male children sometimes perform some of the adult male roles, depending on the conventions of the play. Male actors play all the female roles in Noh even though many of the more important Noh plays center on women. By contrast, as you know, women act in kutiyattam, with the notable exception of the frustrated Surpanakha who is played by a male actor. This sets kutiyattam apart from many other genres of performance in India in which men play all the roles. In Noh there is a chorus of males, differing in number depending on the play. The purpose of the chorus is to chant the text and sometimes take over that task of chanting dialogue from the shite or chief character. The chorus also provides narrative background during many of the dances and is a physical presence occupying special area of the stage appended to the left of the actors as they face the audience. Needless to say, there is no chorus in kutiyattam. Some scholars regard the dances of the central character in Noh as the high point of performance. It is not so easy to cite any single feature of performance as a high point in kutiyattam. To me there are many important features. Certainly dance is not the central feature of a kutiyattam performance. Masks are worn by most of the central characters in Noh and not by secondary or subsidiary characters. A few observer have mistakenly describe the makeup in kutiyattam and kathakali to be masks, and in a sense, to the uninitiated eye, they are certainly masklike in appearance. As you are aware it is absolutely essential that spectators of all the major genres of performance in Kerala see the facial expressions and eye moments of the characters in order to fully savor the emotions of the moment. I am reminded that Appakuttan Nair, the late great supporter and critic of the art, advised me to sit as close to the front of the stage as possible in order to fully experience kutiyattam. Noh depends on rhythm to set the pace of performance. All Noh plays must move through a precise sequence known as jo-ha-kyu (beginning, break, and fast; or slow, faster, and fastest). Although rhythm plays a vital role in the development of a kutiyattam performance there appear to be no fixed process of development like that of the Noh. Three drums are used in Noh and two are particularly required for a performance to take place, along with a wooden flute. As we are aware, the mizhavu is linked to kutiyattam in an intimate and necessary way, along with tiny hand cymbals. Acting and rhythmic accompaniment are fundamental features of kutiyattam performance. As most know, it is important that the mizhavu drums coordinate closely with the actor’s movements and gestures in order to heighten them and appropriately accent them. -5- Other musical instruments are sometime added to the kutiyattam ensemble. And the conch shell serves as an important instrument. There are schools of training for each one of the musical instruments in Noh, just as there are individuals and schools of musical training for artists in kutiyattam. Although kutiyattam has distinct schools of acting, they are not as elaborately organized as the five schools of Noh, among which the Kanze is the oldest. In Noh there are distinct levels of teachers headed by a master teacher and various grades of other instructors moving hierarchically down the ladder with the right to train amateurs in the art of their school. Not long ago I believe the Kanze School could boast that it had as many as a million amateur students learning from many different levels of instructors. Separate schools for studying the secondary or waki roles are also found in Japan. By contrast kutiyattam has relatively few training centers and few students. A comparatively large number of plays constitute the Noh repertory. About 240 or so are regularly performed by some or all the schools and others only in one or a few of the schools. Kutiyattam does not have anywhere near this number of plays in its repertory. And unlike kutiyattam, each Noh play is performed in its entirety from beginning to end. Ordinarily, within the space of only an hour or so. The way serious matter is separated from comic material in Noh is very different from that in kutiyattam. A totally separate genre of performance has sprung up in Japan catering to the demands for comedy. The comic Kyogen plays, with their own repertory, are inserted between Noh plays in a performance program. And the use of comic characters called ai-kyogen within Noh plays are used to separate serious matter from the comic. As we know in kutiyattam, the presence of a vidusaka signals comic material is likely to be forthcoming. Improvisation by the vidusaka clearly sets kutiyattam apart from the Noh that does not admit any improvisation. There is really no character like the vidusaka in Japanese theatre. Noh plays are categorized into five separate types: god plays, warrior play, woman plays, living person plays, and demon plays. As we know, kutiyattam plays fall into categories according to the dictates of the Natyasastra but cannot be categories into such rigid types as prescribed in the Noh theatre. In Japan today, and for sometime since the early part of the 20th century, Noh has been appropriated by the intelligentsia as a sign of personal refinement, hence the large number of students who study and learn to perform Noh in public recitals. Although many amateurs have great skill and knowledge they are not permitted to perform with professional actors. We see nothing like this phenomena in kutiyattam. The closest the Indian public comes to replicating the amateur craze as a sign of refinement is in various genres of Indian dance, particular the bharatanatyam. -6- Noh costumes and masks are now collected and considered prized art objects exhibited in museums throughout the world. Kutiyattam costumes and props have yet to be considered worthy of collection and exhibition. Like Noh teachers, kutiyattam masters possess vast bodies of personal knowledge about performing individual plays and characters. However, they do rely on texts like the various attaprakara and kramadipika inherited from the past that are considered necessary to interpret the plays. Nothing like that exists in Japan, unless you consider the theories of the 14th century master teacher Zeami as a guide. Zeami’s instructions are more general than particular and are often veiled in obscure language. There are markings in published copies of the Noh plays that guide the artists in shaping their recital of the text as well as serving as signals to perform this or that dance. In other words, the play text and performance instructions are blended together. In kutiyattam these matters tend to be kept separate. Noh has enjoyed some distinguished champions in the western world that helped shape public and scholarly opinion about that art. I am thinking of President Ulysses S. Grant who visited Japan in 1879. According to Donald Keene in No: The Classical Theatre of Japan Grant and reported to have said to government officials, “So noble and beautiful an art is easily cheapened and destroyed by the changing tastes of the times. You must make efforts to preserve it.” His recommendations led to improvements in the lot of the companies and the artists. In the early part of the 20th century Ezra Pound and William Butler Yeats both brought world recognition among the intelligentsia to the virtues of Noh through their writings and the praise they lavished on the form. As you may be aware Yeats even composed some plays in the style of the Noh. Noh has always appealed to my aesthetic instinct ever since I was an undergraduate student and well before I came to India for the first time. I have often wondered why I was drawn to kutiyattam: a person living in the west, educated in western theatre traditions, teaching western theatre history and literature, and specializing in directing western plays. If my fate had been different, I think I might well have studied Noh. Well, my attraction to kutiyattam was all due to a number of Indian scholars and artists that led me to better understand and appreciate its unique virtues. Among those individuals Mr. L.S. Rajagopalan stands out. He was the first to teach me to see that kutiyattam is the art of tour de force acting. Step by step, perhaps without even realizing it he was doing so, he sparked my interest in the great roles and the great artists of the day. He introduced me to the late and great Mani Madhava Cakyar’s King Udayana in Svapnavasavadatta. In what may have been among his last performances on the public stage I was fortunate to see Sri Cakyar, who at an advanced age, literally threw away his walking stick as he entered the stage to become a sprightly royal lover pining away for his beloved Vasavadatta. At his home in Likkadi he demonstrated the nava rasas at the behest of Mr. Rajagopalan. Sri Cakyar vividly illustrated to me that kutiyattam acting has the power to transform even the oldest person into the character he portrays. -7- Painkulam Rama Cakyar, my own supervising teacher at the Kerala Kalamandalam never failed to please audiences with his great wit and insightful political and social criticism as the vidusaka in Subadradanamjayam, as well as in other play. As the thwarted Surpanakha, besotted with love for Sri Rama and brought to anger and eventually to destructive reprisal, Painkulam Rama Cakyar exposed the raw power of ritual and improvisation to link modern audiences with ideas in the centuries old epic Ramayana. And not the least among the three greats I was fortunate to see our own Amannur Madhava Cakyar, whose powerful portrayal of the love-blinded and vindictive Ravana never failed to stun and impress audiences, especially in his rendition of kailasodharanam. He also brought Bali to life for me as a powerful, arrogant but flawed monarch. Audiences literally sprang to their feet in tears at the end of Balivandham. All three of these great masters practicing their art before live audiences set an example of the power of kutiyattam acting to raise us above the ordinary and mundane in everyday life and point out man’s virtues as well as his flaws. Mr. Rajagopalan’s insight and the depth of his understanding inspired me to begin to mine the treasures of kutiyattam acting and for that I am forever grateful to him. He is not the only person to whom I owe an eternal debt of gratitude. My asan Sri Kalamandalam Rama Cakyar painstakingly and patiently introduced me to kutiyattam acting from the inside by serving as my teacher at the Kerala Kalamandalam beginning in 1974. Over 30 years ago he guided me step by step through the whole of the Sutradhara’s purapad at the behest of Painkulam Rama Cakyar. As a young artist himself he could ill afford the time away from his own studies to take on this tough assignment: to teach a novice, an awkward older person like myself. But he did so willingly because his teacher gave him this task. Thinking back on that act I am struck by the wisdom that underlies it. Painkulam Rama Cakyar must have known that by teaching your art to others, even to one who will never be a practicing kutiyattam artist, his pupil Rama would better know the role himself. Later, when Rama also took me through the first day of Hanuman’s purapad in Anguliyankam, I dare say he gained new insights into the role. And here lies my point. The teacher/student relationship in kutiyattam is fundamental to the greatness of the art. The transmission of the art, from teacher to student on a personal level, is a process that provides the opportunity for depth and insight to be gained by both student and teacher. In this respect, kutiyattam differs from western acting. It is entirely possible that a western actor may gain notoriety and even stardom without ever having stepped into a classroom, much less teaching others his or her art and craft. Of course there are many notable exceptions. Yet the western actor need not be a student of acting and also he need not be a teacher of actors. In kutiyattam, that is just not possible. You cannot simply pickup kutiyattam acting without being trained. Ordinarily, it takes years of rigorous study to practice kutiyattam. Of course there are some kutiyattam actors who do not teach but I suspect they are few and far between. There are many western actors who do not and should not teach. -8- Western stage actors do not need a good ear for rhythm and music to perform unless they are specialists in musical comedy. Kutiyattam actors need both. Kutiyattam is an intimate ensemble of actors and musicians. In this way, it resembles many other genres of Indian and Asian performance. What struck me most when I was studying with Kalamandalam Rama Cakyar was his instinctive awareness of the rhythm of the mizhavu underlying the gestures and movements required for the role. While learning the Sutradhara purapad I came to realize the importance of its rhythmic accompaniment. Thus kutiyattam actors and musicians are both well-rounded artists, playing off one another throughout each performance in something like the relationship found among western jazz musicians. And finally, during my studies of kutiyattam, I came to respect the bond between performer and performance space that links audiences with the live event. The excellent Ph.D. dissertation of Dr. Clifford R. Jones first introduced me to the religious and technical details of this concept. But it was to my late friend Dr. Govardan Panchal that I owe a personal understanding of this idea. Accompanying him on visits to various kuttampalam I came to see the importance of their contribution to the art of performance, owing to their unique accoustical properties and the ordering of the visual relationships of performers to performance space. These buildings are one of the unique contributions of Kerala to Indian and Asian performing arts. No other Indian genre of performance has shaped a setting for itself like the kutiyattam has done. In Kuttampalam and Kutiyattam Dr. Panchal systematically links their inspiration to ancient traditions of theatre. Dr. Jones, Dr. Panchal and Mr. Rajagopalan have discussed the ritual and religious significance of these spaces. Like the Noh of Japan, kutiyattam is best seen in its intended environment. There is nothing that takes the place of seeing kutiyattam in a kuttampalam. In conclusion, I need not remind you that a great deal has yet to be done to bring the notice of this great art to Kerala, India, and the world. And a great deal needs to be done to sustain and preserve a knowledge of the past, as well as thinking and rethinking potentials for the future. Without meaning to prioritize them the following are among some of my recommendations: 1. Providing a central location with climate control for collecting, assembling, preserving and viewing visual and aural documentation. 2. Establishing a central library for the study of the art that contains both original documents and secondary sources. 3. Establishing a museum with climate control for display of costumes, ornaments, props, models of kuttampalam, musical instruments, and so forth, that will give the general public a taste of the world of kutiyattam. Perhaps, even a traveling exhibition may be successfully mounted that will take elements of the main collection around the country. 4. Carefully prepared and executed “tourist” presentations that will appeal to the interest of Kerala’s growing tourist industry without sacrificing the integrity of the art. -9- 5. Regular presentations of complete, full-scale performances in kuttampalam in selected sites in the state and touring performances designed to replicate the atmosphere of these works in places where there are no kuttampalam. 6. Continuing to make a video archive of performances of all the works in the repertory and providing access to some or part of that archive on television and on the Internet. 7. Publications of scholarly works of translations of plays, scenes, and the attaprakara and kramadipika. 8. Publication of comparative works in which kutiyattam is measured against other famous Kerala genres of performance, as well as those throughout India. And the list could go on and on. Needless to say, we are at the beginning of a new era in this age of proliferation of information and easy access to vast quantities of material throughout the world owing to the Internet. Kutiyattam will surely play a role in the coming era. We can only hope that it will do so without loosing the original integrity and charm that has made it so dear to all of us assembled here. Thank you. - 10 -